John Green talks KU Common Book The Anthropocene Reviewed | News

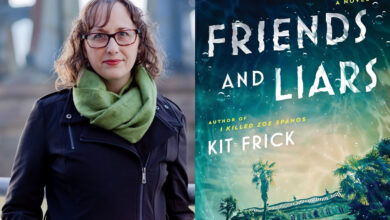

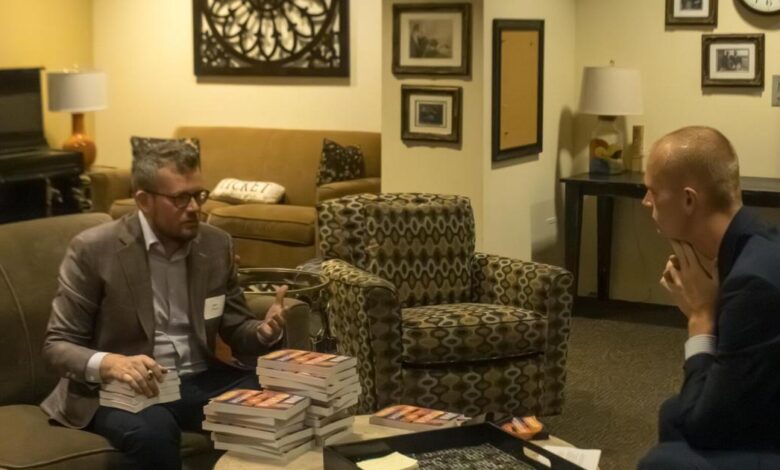

Bestselling author John Green visited the University of Kansas Tuesday night to speak about his book “The Anthropocene Reviewed,” this year’s KU Common Book. Green is a bestselling author of novels including “The Fault in Our Stars” and “Turtles All the Way Down” and a co-creator of the educational YouTube channel Crash Course. Before the event, Green sat down with University Daily Kansan senior reporter Harry Whited to discuss the book. That exclusive interview is published here in question-and-answer format, with minor editing for clarity.

Whited – So to start off, in your book, you discuss the importance of people experiencing life in its entirety. Both the good and the bad aspects of it. How do you think the world would look if more people kind of took your advice and actually experienced life in its entirety? And what do you think college students could get out of that message?

Green – Well, I think one of the hardest things about being a person right now is the virtualization of experience, which in some ways is exciting and intoxicating and in other ways is quite worrying to me. I don’t know how to make sense of it, and so I tried to make a little bit of sense of it in this book because writing is my way of thinking.

But I have so little advice for college students because I do not have any idea what it would be like to be a college student in the year of our Lord 2025. It seems like it would be very difficult. There’s a lot to navigate. I do not know what it’s like to go to college in a world of AI, let alone in a world of Twitter and Tumblr and Facebook and everything else and Snapchat and everything else.

So I’m always hesitant to give advice to young people because my life was so different, and I don’t want to apply my experiences to their experience in a way that might not ultimately be helpful. I do think in my own life it’s been very helpful to, for lack of a better term, go outside. I spent today in downtown Lawrence with friends who own the great store Wonder Fair. And to be with people you care about, experiencing a cool place like Lawrence is really valuable. So that’s my biggest piece of advice.

You kind of talk about that in the book a little bit, talking about observation, especially the chapter about the Ginkgo trees, that’s something that really kind of stuck out to me, is people’s observations of the world.

I think it’s really important to pay attention.

So how can people better learn to pay attention in a world that’s so filled with distraction and just kind of overall noise?

It’s really hard for me to pay attention. This book was my way of trying to pay attention. I think writing things down is one way for me, at least, one way we observe our own experience and our experience of the world.

But I also think I don’t want to be dismissive of online experience when I’ve benefited so much from it in my own life. I have met people I never would have met. I’ve learned about experiences I never would have learned. And so I think you can also pay careful attention in distraction-rich environments like the internet. But it’s certainly easier when you’re, you know, walking through a prairie, to pay that kind of sustained attention to the world.

You said that when you write, you kind of write to work your way through something. And so this book kind of came out of the COVID era. Now with the Anthropocene post-COVID, how are we doing in John Green’s judgment? How are we kind of doing post-COVID?

What’s my overall star rating for humanity in 2025?

Yeah, like post-COVID.

Yeah, I mean, the first thing I’d change is that we’re not post-COVID, right? Like we live in a world where COVID is an ongoing illness and, you know, sickens lots of people, disables lots of people and continues to kill people.

But I don’t think we have reckoned meaningfully with how much COVID has changed our social order and how much it affected the lives of especially young people. I mean, how old are you?

I’m 22.

So you were in high school or college?

Yeah, I was in high school. It broke out my sophomore year of high school.

And so your entire late adolescence was profoundly shaped by infectious disease. And I don’t know that we’ve really reckoned with how much it shaped the social order or how much maybe it’s still shaping the social order. And so that’s definitely of interest to me.

I mean, I write a lot about disease because I think disease is, for lack of a better word, important. You know, we live in a world where 93% of people die of disease. And yet we sort of marginalize it when it comes to thinking about world history and our collective choices as people. So, yeah, I don’t know how I would review us in this current moment except to say that I think we still need to reckon a little bit with how much young people, especially, were affected by the profound shift.

And I know for my kids, my kids were in kindergarten and fourth grade. Like those were hugely important times in their development that were really upended by this disease. So, yeah, I’m not sure. I mean, part of the joke of the book, right, is that you can’t distill things down to star ratings. It’s the wrong way to look at the world. We shouldn’t use a single data point. But I’m really concerned about this moment in history. I’ve never been, in my lifetime, I’ve never been, I’ve never experienced a social order so disunited.

You have kind of moved into writing more nonfiction, specifically. I mean, you’ve done, you know, the Crash Course and everything and connected with people that way. So why this move toward writing more nonfiction? Because you have this tuberculosis book, you have this book. Do you feel like you can connect with people better that way? Do people seem to listen to more nonfiction?

I did not know how to respond to this moment with fiction, I guess, is how I would answer that question. I wanted to, I miss writing fiction, I love writing fiction, but there were aspects of the time that I was living through that I didn’t know how I could use fiction to respond to it. And so I found myself wanting to write a memoir. I found myself wanting to write about the places where my little life rubs up against the big social forces of my time.

I didn’t know how to do that. And then I kept thinking about this joke that my brother and I had when we were on the road for my last novel in 2017, where we would look up the one-star reviews of national parks and laugh at them. And that became my way into writing a memoir. Like it’s sort of, this is a collection of essays, but to me, in my experience of writing it, it’s a secret memoir.

Do you think others could get that same kind of fulfillment out of it? Out of writing, out of reading?

Yeah. One of the coolest things that’s happened from this book is people writing their own reviews of their own experiences. I read a review of road trips that was about a young man who is traveling across the country with his brother, who had cancer. And I read it when my brother had cancer. And that was one of the most fulfilling things that’s ever emerged from my work.

The coolest thing that can happen to you as an artist is to have people make art about your art, have people respond to your work with their own stuff. The best part about KU having this book as the common read, for me, the most fulfilling part for me, is people making art in response to it.

I was over at the Bob Dole Institute, and there was a group of young people who sang a barbershop version of “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” which I write about in the book. That kind of thing is so overwhelmingly gratifying that I don’t even know how to express it, really. But it’s the coolest thing that can happen.

And so I do hope that people will respond to this book by at least thinking about what they’d write about and maybe also writing. Thinking about how they’d approach the questions of their own lives through essays.

This place is sold out within three days to see you. Did the John Green, working at Booklist Magazine, ever think that you’d get to this point?

No, the John Green Working at Booklist Magazine did not imagine this. Indeed, the John Green who wrote this book didn’t imagine this. Didn’t imagine that – you know, it’s hugely fulfilling to have your book read in an academic setting, to have young people reading the book together in the community. It’s hard to explain how meaningful that is to me, how much a dream come true that is.

But the weird thing about being a person is that you can’t imagine the future. You can’t imagine the wonderful things that are coming. You can’t imagine the terrible things that are coming. You can’t imagine how good it will be. You can’t imagine how bad it will be.

And I kind of thought when I was your age, I sort of thought, “well, by the time I’m in my 40s, I’ll have a clearer idea of what the world looks like.” But I find that I don’t. All I have is an ongoing curiosity, which I don’t mean in a positive way, necessarily. I mean that in like, you know, there’s curiosity. The world I live in is horrible and wondrous, and I can’t separate the horror from the wonder. I can’t figure out my way through, I can’t figure out my way to a star rating of this experience of consciousness. All I can do is try to observe what I observe as I observe it.

I kind of asked you to predict the future with my first few questions here. Why do you think people do that with you? I’m sure this isn’t the first time someone’s asked you a question like that.

I think because I’ve talked a lot about history in my life, and for a lot of kids your age, I was part of their history education. And I’m sorry to call you a kid; for a lot of young men your age, I was part of their education. For young people your age, I was part of their education. I think there is an expectation that an understanding of history informs an ability to predict the future. But I can tell you with some certainty I can’t predict the future.

So like, I remember my roommate when I was in my early 20s, she came home one day and she was like, “Hey, I got this new thing called wireless internet.”

And I was like, “That’s cool, but we don’t need wireless internet because I have a 100-foot Ethernet cord. And that goes as far as the wireless does. This wireless stuff will never catch on. 100-foot Ethernet cords are the future.” And that was wrong. So don’t believe anything I have to say about the future.

Indeed, I’m not sure that you should trust any person in their predictions about the future. The future is something that we will unfold together. The future is a collection of the choices that we’re making now.

And also, the future is what we can’t see coming. You know, I mean, I certainly saw pandemics coming, but I didn’t see COVID coming. If you’d asked me how a pandemic was going to play out in 2018, I would have predicted it very differently from how it played out. I wouldn’t have understood the extent to which misinformation would be a key factor. And I wouldn’t have understood the extent to which it would increase polarization in communities. I wouldn’t have understood any of that. So yeah, I think people tend to be pretty bad at predicting the future.

I like the quote you have from your brother in here, where he’s like, “The species will survive this.”

Yeah, yeah, yeah. That was my brother’s big hope at the time.

And that kind of paid off. I mean, we did survive it.

He was right, right? Like he didn’t want to provide me with false hope, but he was right.

Source link