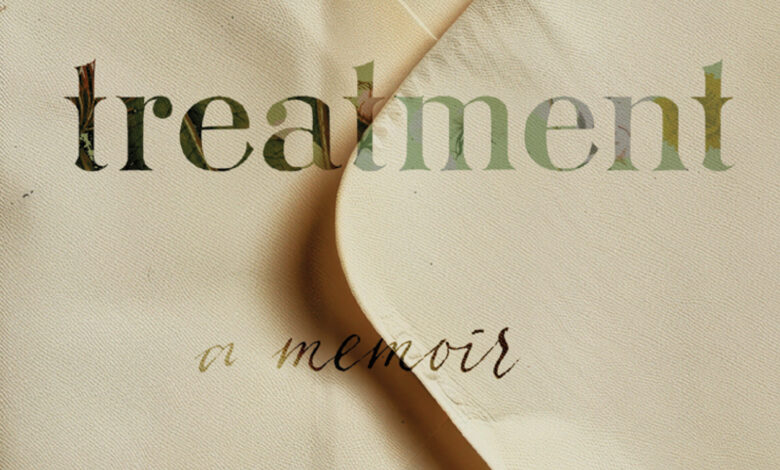

Q&A with Jeannie Vanasco, Author of ‘A Silent Treatment’

One of Baltimore’s most beloved memoirists, Towson University professor Jeannie Vanasco, has a new book out this month. Fans of The Glass Eye (2017) and Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was A Girl (2019), as well as those new to Vanasco’s work, are eager to get their hands on A Silent Treatment, which focuses on the fraught relationship between the author and her mother after the latter moves in with Vanasco and her partner.

As the Booklist critic put it in a starred review, “Vanasco has a beautiful and elastic compassion for her mother that anyone familiar with a complicated parental relationship will relate to. Overall, a beautiful gift to all who have struggled to care for a loved one in the way they needed.” A conversation with the author and launch details below.

As you explain in the memoir, you spent your childhood in Sandusky, Ohio. How did you end up in Baltimore?

Towson University hired me to teach creative nonfiction. First question they asked at the interview: “What is creative nonfiction?” I said I didn’t know. I remember thinking, Well, didn’t get that job. Nine years and three books later, I still don’t know the answer.

The “silent treatment” in the book begins shortly after your mother moves from Ohio to to a renovated basement apartment in your house. Later, she moves to an apartment across the street. Your neighborhood and your neighbors are important elements into your memoir.

During my mom’s silences, I’d often park a block or two from our house and write in my car. If I felt social, I’d roll down the windows. I met some fascinating neighbors that way. We had one—she’s since moved—who’d sometimes take stuff out of our trash and turn it into her lawn ornaments. So whenever my mom threw away something nice the day after trash pickup—just to communicate her anger—I’d know where to retrieve it. We live in Rosebank, right down the street from Belvedere Square. I love our neighborhood. We’ve got Swallow at the Hollow and Hex Superette. I figure the kombucha cancels out the vodka.

Here’s a thought I had: Because your mother is quoted so often in the book, with her epigrammatic comments appearing in parentheses on practically every page, the tortuous silence experienced by the narrator is as much corrected by the book as conveyed. Maybe the book could be thought of as “Remedy for a Silent Treatment.”

I like that. My mom, in her absence, felt more present than ever. The parentheticals helped me enact that feeling on the page—and interrupting the narrative with her dialogue—both spoken and written, from long ago and from very recently—helped me transition between past and present. Once I landed on that formal technique—a year or so into the project—the scenes and reflection started clicking together.

You’re an associate prof at Towson. Classroom scenes, textual analysis, and writing prompts are included in the book. Do you feel that there’s an interplay between teaching and writing?

Writing is noticing, and as a writing teacher, I spend a lot of time noticing craft techniques—which is both useful to me and a problem. Once you accumulate enough tricks, you can forget them when you write, but as a teacher I need to explain why, say, anadiplosis [repeating the last word or words of a clause or sentence as the beginning of the next] gives the effect it gives. I’d like to turn off that part of my brain, but as a writing instructor it’s hard.

Bureaucratic problems arise because actually, you and your mother have the exact same name: Barbara Jean Vanasco, and then you end up with the same address too.

Yeah, we got flagged for voter fraud. On the bright side, my credit score improved. According to the three credit bureaus, I opened my first line of credit in preschool.

Your partner is like an oasis of calm and rationality amid two women who both seem to be having nervous breakdowns. Like your mom, he gives his permission and support for you to write about him, though near the end he says he would be fine with it if he were not the subject of a whole future book. What’s it like, writing in realtime about the people you live with?

I’m frosting that on Chris’s next birthday cake: “an oasis of calm and rationality.” Writing about people you live with—it’s tough, for sure. My car became my home office. I spent a lot of time driving aimlessly and rambling to my voice memo app. Labi Siffre’s “Crying Laughing Loving Lying” looped during some truly deranged voice memos—in one I quoted a henku, a haiku about hens. Nervous breakdown is accurate. But I tried to keep it funny for myself: otherwise, I might have drafted A Silent Treatment inside Sheppard Pratt. Thankfully, I stuck to the hospital parking lot. It’s not a bad place to work.

I of course never want loved ones to think they’re always on the record. They’re not. Some moments, I consider, off limits. And I always ask loved ones to read the manuscript before it reaches production. My mom, though, says she’ll read A Silent Treatment after it’s published. She says it’s my book, that it’s not her place to say what I can and can’t include. A memoirist couldn’t ask for a better mom.

This is the first I’ve heard of a catio! Cats and catios are important in the book. At one point you worry to Chris that you haven’t given them enough attention for how present they were, on your lap throughout the writing.

I wish I could write a book about Kiffawiffick, Catullus, and Hildegard. Problem is, it’d probably be boring. They’re too perfect. Sure, they’ve scratched up our furniture, but it’s not really their fault. We own more cat furniture than human furniture.

And dogs are important too – your mother cites her dog Max as “all she has.”

My mom is the biggest animal lover I know. She’s a vegan. She will not tolerate animal cruelty. She had an extremely abusive childhood and abusive first marriage, and she turned to her dogs and cats for love. The book used to have way more dog and cat scenes in it. When she described her pets as all she had, I knew not to take it personally. She was feeling lonely.

Friendships, and particularly friendships with other writers, seem to be a real bedrock element of your life.

I can’t imagine my life without friends—especially writer friends. Writing is hard work, and it’s good to be around people who understand that. I think about my mom’s situation—how she moved here knowing only Chris and me. It was extremely brave of her, and if anybody reading this has an adult parent moving in, do your best to help them find a community. And maintain your friendships.

Your three memoirs almost seem like a trilogy to me… elaborating a particular approach or method to understanding one’s past and one’s family. How do you see it? What has been the development?

Writing memoirs can feel like a betrayal to one’s family, but the greater betrayal is to support the idea that anybody human is perfect. It’s not fair to them. I guess my memoirs reflect my delayed adolescence. I finally see my parents as imperfect parents. My approach to memoir is also changing. I increasingly mistrust hindsight. I don’t think we ever have perspective. I think the moment that we’re experiencing is the truest thing.

Launch details:

Jeannie Vanasco in conversation with Michelle Orange

Wednesday, September 10, 5:00PM

HEX Superette, 5718 York Rd

Related

Source link