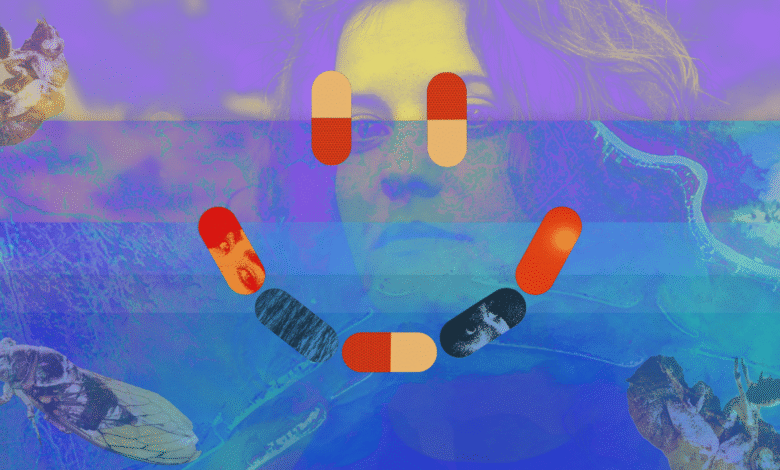

New Cli-Fi Novel Gropes for Happiness through the Dark of Texas Blackouts and Louisiana Heat – Deceleration

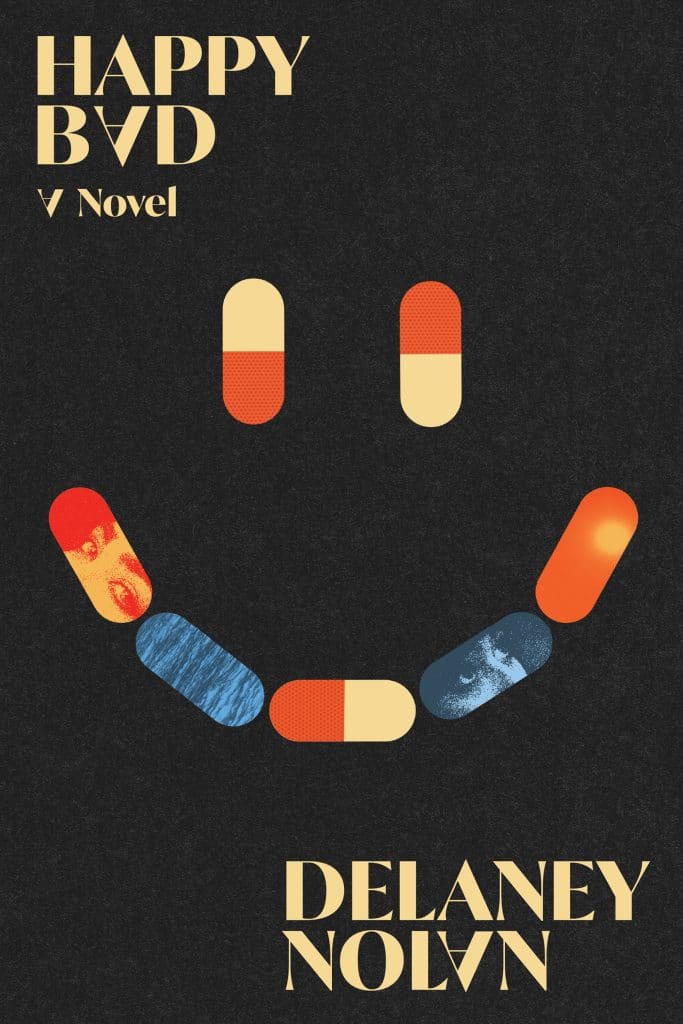

HAPPY BAD

by Delaney Nolan

Astra Publishing House (October 14, 2025)

Delaney Nolan’s many-splendored debut novel Happy Bad is set 20 years hence, and the good news is humanity still exists in a semblance of a world we recognize—if one with severe water restrictions, far fewer insects, and artificial foodstuffs that simultaneously sustain life and diminish it qualitatively. The really bad news, however, is that the oligarchs are still oligarching and the masses are still marinating in an oppressive slurry of corporate and government overreach, greed, and power tripping, especially over young women’s bodies, biology, and behavior.

Set in a residential treatment center for teenage girls, Nolan’s protagonist Beatrice is monitoring the Phase III pharmaceutical trials for TENDER KARE’S new drug BeZen, a powerful mood alterer that “required only water and a swallow, no further sacrifice, and all your troubles would be swept down to the bottom of an inner sea.”

If some of her notations for TENDER KARE swell with creative and comically farfetched pseudoscience, when a heatwave and blackout hit, Beatrice does whatever’s necessary to propel the girls out of a sweltering and mostly abandoned Askewn, Texas, and shepherd them through a mass evacuation towards the gleaming corporate towers of Atlanta.

For all of her exertions, by turns admirable and criminal—and sometimes both—Beatrice’s determination and ambition mirror Nolan’s own in creating a work that is part action novel and, via flashbacks into Beatrice’s upbringing, part analysis of how on earth we got here.

Happy Bad confronts a raised fistful of the most urgent and existential issues of our hour, presenting by force of Nolan’s expansive imagination one detailed and layered vector of possible futures—the one perhaps most likely given the current inattention and inaction on climate. Yet for all of the frequently stunning political insights Nolan offers up on nearly every page, the shining star of this exciting and entertaining work of climate fiction is the writing itself.

A graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop and fellow member of the National Writer’s Union, Nolan’s Happy Bad delivers pure literary pleasure that arrests, surprises, and jolts its readers out of reverie and into refusal of this wasteland of a truncated reality that simply must be rewritten, for the sake of the girls and all of life.

Read for yourself, from a chapter early in the novel that echoes all our lived and witnessed memories of the hurricanes and flash floods of previous climate disasters, courtesy of Astra Publishing House. A Q&A with the author follows.

Excerpt from HAPPY BAD

In the lobby the air was thick with the heat of anxious people. There were maybe forty of us surging around the cramped lobby, all unsure what was going on. A group of young men were arguing behind the desk, each shouting in a different key, but I couldn’t tell if they were employees. I didn’t see Samuel. Papers were scattered all over the ground; I plucked one from the air as a hot gritty wind from the open door blew it past, and two more people blasted inside:

VOLUNTARY EVACUATION, it read. No time frame for power restoration. Leave if possible. Then the useless FEMA hotline number.

It was dim in there. I pulled Teresa backward and wedged us between the edge of the crowd and the doors. We looked outside in silence as the dust storm approached. The lobby grew quiet. The storm looked about twenty blocks away. We held still. People’s eyes were glued on the doors. The lobby grew darker, the sirens somewhat muffled. Ten blocks away. Silent. Five blocks. One. And then it swept over us, and with a great inward gasp the lobby grew dark, very dark.

But the truth, the surprising truth about being within the cataract of dirt? It was nice. We were inside a cool bubble of time. Nothing but dust could reach us, not even sunlight, not even telephones. The doors rattled in the wind as the men who’d been arguing stripped off their shirts. A businesswoman emptied a bottle of water over the shirts, and they—we; I helped—stuffed the shirts into the cracks, between and around the doors, to keep out the fine brown silt, much of which had already found its way in, setting off fits of coughs. The wind and the hiss of sand covered everything. It could have been nighttime, dark and faintly orange. The world existed only two feet past the walls of the rental building; beyond that it stopped.

“It’ll die down,” said a girl in athletic clothes after a minute, her voice breaking through the soft timpani of dirt on glass.

“This is bullshit,” groaned a young man who’d been poking around the counter. “I’ve seen these before,” said the athlete’s boyfriend. “They pass. Don’t worry, everyone!”

“Sure, we know,” muttered his partner, now squatting on the floor, facing away from him. “Does anyone work here?” I whispered to her, kneeling. “Is anyone getting keys?”

She shrugged and looked back at the black dust outside. I texted Frank, chances of van rental not looking good.

The crowd was hypnotized. We’d seen dust storms before, but this was a bad one. Some sat down to wait. Outside, we watched a loose car muffler throw sparks through the dimness as the wind dragged it along the sidewalk. Teresa drummed out a tune on the fire hose cabinet. Once, twice, three times, a pedestrian burst through the doors: Visibility was almost zero, but each time someone resolved out of the darkness, we’d haul open the doors just as they arrived, and they’d stumble in hacking and gasping, and we’d push the door closed ASAP on its pneumatic hinge while someone patted the arrival’s back, congenially beating the dust off their clothes. I guess I was witnessing goodwill. The irritated man who’d been behind the desk now made runs to bring water in wax paper cups. Something about being trapped together was, somehow, lifting our spirits; a sense of camaraderie spilled around. We were part of something! People sat on their heels against the wall, trading Where were you when the power went out? stories. I was sweeping the floor. I was calling my mother. I thought of the Askewn mall, Bing Hooper’s simpering face. I did not want to be stuck here. I realized abruptly that Teresa was no longer at my elbow.

I wheeled backward out of the crowd and looked around for her, white-knuckling my own calm. I had no bad intentions at this point. I walked the lobby. From the desk I plucked up a dusty and discarded surgical mask. I looked behind the desk, checked the toilets, considered the ceiling tiles with a pounding heart. And then I spotted her, sitting calmly in a plastic chair against the far wall, underneath a dead TV. She sat there, patient. Trusting me to figure it out. All the people back at Twin Bridge: trusting me to figure it out. I would have to be bold! I would have to take action!! The truth is, I saw people, children, do reckless things all the time, and they always, always, always survived in some sense, and what did they say about beauty and intelligence? You get to pick just one? I choose neither. I held out the surgical mask to Teresa, and for a terrible moment, we must have understood one another, because she lifted her hands from her lap, untwisted them like a trumpet flower or the cracked bottom of a vase, and revealed that secreted within she held a set of keys.

“You wanted these?” she asked and smiled gently.

I plucked the keys from her outstretched hand.

On a scrap of white paper scotch-taped to the fob, the words VAN FOUR.

“Where did you get these from?” I whispered.

She pointed toward the back, behind the desk. “In there. A key locker.”

It simply wasn’t permitted for me to tell her, good job. I told her telepathically instead and then pulled her to standing. Without speaking, she followed me behind the desk. There was the key locker, standing open. Soon enough someone else would get the same idea.

I continued down a hallway that opened behind the desk, toward a glowing emergency exit sign that no one had surrounded because its sidelight faced a dumpster. I waited until she looped the mask’s elastic around her ears. Gently, I pinched the metal band around her nose to keep it tight. Outside, in the darkness, were the vans. And now was the time to take one. I gripped Teresa’s hand, and under the dim green light of the sign, pushed forward, into the punishing world.

Q&A with Author Delaney Nolan

Frances Madeson: Because your protagonist is named Beatrice and the hardships in the book loosely correlate to circles of climate and societal hell, I checked in with Dante’s The Divine Comedy. My eye landed on this quote in Canto II where Beatrice says:

God in His mercy such created me

That misery of yours attains me not,

Nor any flame assails me of this burning.

Then I thought of your Beatrice, and how she has that character arc of moving from someone who is efficient and kind in a certain way, but also aloof, to the (quoting from the text) “things that happened at work—the vomit, the mania, the tampons thrown at heads—all that I kept in a hazard-orange bucket in my heart, which was sealed the moment I walked out the doors of Twin Bridge.” Shepherding her charges through a heatwave and blackout that begins at the Twin Bridge residential facility does bring her into solidarity with the girls she’s been monitoring, and it’s transformative. I was wondering about the connection with Dante for you?

Delaney Nolan: It’s been a long time since I read Divine Comedy; I remember [Dante’s Beatrice] as a guide, so there’s that. But I don’t think there really was a direct connection. I love the way that you’ve described Beatrice’s movement through the story [Happy Bad], and I think that’s a great way to put it, that in the beginning she’s efficient but aloof, and by the end, she’s brought into a position where she’s in solidarity, but in a way that also makes her more vulnerable.

The Twin Bridge works both ways, doesn’t it?

There were a lot of reasons that a twin bridge felt right as a symbol: this idea of parallels and mutual feedback and going from one place to another as other people are crossing back in the opposite direction.

It is also a little bit inspired by different institutions or organizations I’ve worked with—an actual treatment center, but also the time I was working at a refugee reception center in Greece, and here in New Orleans working in some mutual aid organizations. And I was interested in the way that sometimes these places that are meant to protect and help marginalized and vulnerable communities end up, in the name of protection, recreating some of these same systems of power and control, parallel systems of power and control, that have done this harm in the first place.

At the end of the excerpt, with Beatrice as our narrator, you write: “I gripped Teresa’s hand, and under the dim green light of the sign pushed forward into the punishing world.” What is your writerly vision of the punishing world?

I’m interested in what can be accomplished on the line level and whenever I can find a thought or a sentence that feels like it is holding two things at once, and it’s both describing the immediate action, but also at the same time, speaking to some larger sweep of feeling of the character or the world.

And of course, a big part of this book is my interest in people who are navigating life with reduced capabilities, or who are struggling with just the day-to-day labor of living. And I think so much of writing comes down to that, how do you keep moving through the world one day at a time when sometimes it can be so difficult, even just to go one minute to the next? So I generally wanted to show that it’s difficult out there.

You situated the scene “within the cataract of dirt,” but also “inside a cool bubble of time.” These phrases are so expressively idiosyncratic. How did these marvelous depictions come to be formed?

Part of it is from a bit of reading and research on the Dust Bowl era in the Lower Plains in the 1920s and ‘30s, when there were these huge dust storms that did swallow roads and suffocate cattle. And part of working on this, I was in Nebraska City, and I remember going to a taxidermy museum there and talking to the proprietor, who had been there all his life.

And he was talking about being in Nebraska during the Dust Bowl time, when he was very, very young, and it hadn’t rained in so, so long. And they were outside, and he looked up and saw a cloud in the distance and thought, oh my God, finally rain. And they watched as it got closer, and they realized—it was a huge swarm of locusts.

Hearing stories about things that seem like they should be inconceivable because they are so extreme, and then one day they just begin happening, which is something we all lived through—the pandemic. Just understanding that what is possible in the world can change very abruptly and pretty permanently sometimes.

One of the things that impressed me the most in the book, or that I completely identified with having lived in Louisiana during hurricanes Delta, Laura, Zeta, and Ida, was the vilification of FEMA and the monopoly utility that kept the power off in swaths of New Orleans for weeks after Ida. Why were FEMA and Powergy targets of the book’s wrath, and not a politician or corporate exec? Why go for these kind of institutions?

When I first started working on it, I was thinking about Katrina in 2005 in New Orleans. But then I had my own experiences with FEMA after Ida, there was some frustration sometimes with getting FEMA funds. And both my brothers went through Helene. And now, of course, they’re talking about eliminating FEMA, and so it’s like being mad at some employee of a business, and then finding out that the whole thing is going to shut down and go away, when we just want you to work better.

But I was hoping to not make anyone look like a single bad guy. But rather, look at how some of these overlapping systems that are essentially privatizing utilities and necessary aid inevitably don’t serve us the way people need them to in an emergency. And it is complicated, and there rarely is a single villain. But that’s how these systems end up being so broken, because it’s never anyone’s fault, and it’s always a problem of doing more paperwork, or waiting for the litigation to settle, and so there’s never one person that you can really point to and be mad at. So really, what I was trying to get across is that, yeah, the villain is being forced to navigate bureaucracy for your survival, which also does the work of making it feel like it’s your fault if you’re not able to do that successfully.

This part of the action with Beatrice and Teresa evoked a Thelma and Louise vibe, the way they cross some serious lines. But in your telling they don’t self-destruct, they don’t even consider it. And I found that exhilarating. Without spoilers, what changes for them after they drive away?

We don’t know immediately what has changed, certainly for Teresa, but for Beatrice, as they drive away in the following chapter, the realm of what is possible has suddenly given way beneath her feet, and she is navigating new territory. Part of the challenge was figuring out how to make that both realistic but still energetic and entertaining. In Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, after Raskolnikov murders the old woman, the insane tension and delicious nervousness of him figuring out what to do next, and how to get out of there, and how to get away with it, and this other state it kind of puts him in, where all these things that were possible have suddenly collapsed into a single reality. That is, maybe it’s not something he can navigate as well as he expected to.

So I think what’s changed for her as they drive away is, all of a sudden things have become much more real. And this person who thought that she was capable by virtue of being fairly detached suddenly finds herself stumbling over and over, and aware that she’s stumbling and aware that she’s no longer making sense and navigating things well.

I thought you took it pretty easy on the older generation, with the very sympathetic character of her co-worker Arda. And then in what I found to be an incredibly blistering insight, Beatrice is thinking about a point in her mother’s life when she was overtaken by franticness:

“It wasn’t helped by the cession of the Louisiana coast, an event that made the older generation behave weird to the extreme, that seemed to prompt an epidemic of unhinged among U.S. adults as they could no longer deny that things were changing drastically and irrevocably. Yet everyone seemed surprised.”

That’s a huge part of the secret concern underlying a lot of the book. The base feeling that inspires this book is being at a climate protest in Brussels in 2018, it was one of the Youth Climate protests. I remember being so touched, just heartbroken, looking at—I’m gonna cry just thinking about it—looking at all these kids and their parents. Especially the parents who all they wanted was to keep their kids safe, and to have a world where their kid is going to be able to grow up and be healthy and capable and not have a world that’s too shattered for them to survive.

I think about Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and how what is so frightening about it is the idea at its base: the real terror is this idea of leaving a worse world for your child and not being able to be there to protect them. So that was the fear undercurrent of the book. And then at the same time, this idea of what’s called “shifting baseline syndrome,” which is essentially the idea that as things change, they change slowly enough that we’re getting used to the new normal.

We’re all experiencing that, our slow slide towards authoritarianism, in a political way. But also, when we were kids, we were used to there being more bugs. And kids today have a different idea of having fewer bugs outside as normal, and that doesn’t seem strange, because that’s just what they are growing up and getting used to. As adults also, we slowly get used to a slightly different amount of heat and animals. The idea of slowly getting used to a new normal and being able to deny the changes that way was a huge current [in the novel].

I’m interested in: what will, if anything, make that change finally stark and undeniable, and how people would react to that?

One of the surprising and wonderful parts of reading Happy Bad is that readers get to confront young female rage. You just don’t see it often enough, and this drug TENDER KARE has concocted is explicitly trying to erase it.

God, I feel like we’re all so hungry for more art about it, to be honest. I do think it’s such a powerful and neglected fuel source, basically something that we’ve gotten better at acknowledging over the last one or two decades.

I was kind of a mad teenage girl, and I felt like I didn’t know what to do with that, and I didn’t feel like that was really being recognized or validated, or depicted in art and the media in a way that I could understand.

I see we have a little more art about, like, women being insane or violent, or cannibals like Yellowjackets. But I think there is still a serious gap in the acknowledgement of how angry women are. And we’re just getting angrier too, at least in the U.S., as we are both exposed more to the things that we are missing, while at the same time having some of our rights taken away. You know, particularly here in the Deep South, over just the course of writing this book, abortion was criminalized. So it was interesting to be writing a book that is interested in young female rage at a time when my own human rights were being taken away.

Why did you set it in Texas and end it in South Louisiana?

I was familiar with the area, and East Texas and South and Southwest Louisiana are also the places that are most at risk of deadly wet-bulb temperatures, which is the measure of heat and humidity that ends up being eventually deadly.

A friend pointed out that sometimes these places that are on the geographic or political or economic margins are also the places where new things and new ways of living become possible, because they are outside the scope of observation or surveillance or control. They’ve been sacrificed already, they can live outside the eye.

Without revealing any plot points, I found the ending extremely satisfying, but was maybe a little surprised that you didn’t pursue accountability, albeit fictionally?

Disasters are good cover for a lot; a lot of people got away with a lot of things, terrible things after Katrina, for sure: the white vigilantes in Algiers.

But I think also there isn’t really justice or accountability in real life, which is part of why I felt like the story did not necessarily demand it. Even though it’s sort of a human craving.

-30-

Excerpted from HAPPY BAD by Delaney Nolan. Copyright © 2025 by Delaney Nolan. Published on October 14, 2025 by Astra Publishing House. Reprinted by permission.

Source link