Susan Orlean on a ‘Joyride’ of journalism and storytelling • Oregon ArtsWatch

“If I were a bitch, I’d be in love with Biff Truesdale.”

So begins American journalist Susan Orlean’s profile of Biff Truesdale, published in the Feb. 20, 1995, edition of The New Yorker in advance of Biff’s appearance at the Westminster Kennel Club’s show that year, where he contended for Best in Show (he lost, to a Scottish terrier).

The profile goes on to regale readers with all manner of information people might like to know about Biff, and more — including a minute description of his body, how he spends Christmas, and who he gets along with (everyone, with the exception of one son named Biffle). Orlean spent time with the boxer’s owners and handler, as well as observing him perform in a show leading up to Westminster.

Orlean is a longtime staff writer for The New Yorker and the author of books including The Orchid Thief (adapted in the 2002 film Adaptation) and The Library Book, about the history of the Los Angeles Public Library and the 1986 fire that destroyed or damaged more than one million books in the library’s collection and remains the largest fire suffered by a public library.

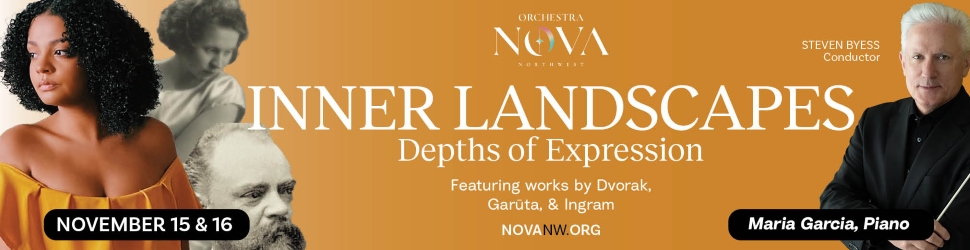

Orlean will appear Saturday at the Portland Book Festival to discuss her newest book, Joyride (Avid Reader Press, 353 pages, $32). Joyride is memoir — the first time Orlean has turned her keen observational eye toward herself.

“The story of my life is the story of my stories,” she writes. Joyride chronicles Orlean’s writing career — from her college newspaper to four years at Willamette Week in Portland, where she said she “became a real writer,” to eventually joining The New Yorker’s staff.

Orlean is one of America’s most singular journalists and one of the most influential practitioners of American literary journalism (also known, variously, as “narrative journalism” or “new journalism”).

Her subjects have included people as ordinary as a group of teenage surfer girls in Maui and a New York City real estate agent to more well-known subjects, including Oregonian and Olympic ice skater Tonya Harding, and the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and Rajneeshpuram in Eastern Oregon. Her books, about seemingly ordinary subjects such as orchids and the Los Angeles Public Library, also chronicle utterly eccentric people, including John Laroche, the gap-toothed erratic horticulturist who is the central character of The Orchid Thief, and Charles Lummis, an early librarian in Los Angeles, profiled in The Library Book.

Orlean has been guided by her curiosity and “the drive from ignorance to knowledge.”

“Writing is a job,” Orlean writes, “but for me it has always seemed like a mission. I felt called, I really did, to describe ordinary life in a way that revealed its complexity and poetry –– to show how rewarding it is to be open to and curious about the world, and how much joy can be found in letting yourself be surprised.”

Parts of Joyride read like a tutorial on how to become a great writer, with Orlean writing at length about craft and the elements of good writing, including detailing the importance of spending time to think about a story before writing it, how to engage readers, and how she realized that the rhythm, musicality, and voice would distinguish her from other journalists.

Joyride also reveals how Orlean endured the vagaries of book publishing, including changing editors multiple times, negotiating book deadlines, a canceled book contract, and other pitfalls of a competitive and fragile industry.

Through it all, Orlean was driven by sheer determination and single-minded resolve to have a successful writing career. “Writing always felt elemental to me,” Orlean reflects. “It was something I wanted to do as soon as I realized it could be done.”

Joyride includes an appendix of five articles, “examples of the work that paved the way to where I’ve landed,” Orlean writes. Those include “The American Man at Age 10,” which appeared in Esquire in 1992. Orlean’s most anthologized piece, it helped catapult her career.

Other pieces include “Be a Joke Unto Yourself,” her article about Rajneeshpuram, published in The Village Voicein 1982, “Devotion Road,” published in The New Yorker in 1995, about a traveling gospel choir, and two shorter pieces published in the Boston Phoenix and Boston Globe.

Orlean will appear in conversation with Literary Arts’ executive director Andrew Proctor in the Newmark Theater at Portland’5. Bright and early at 10 a.m., their conversation is one of the first events to kick off the book festival. On Thursday, the festival announced that, for the first time, the festival has sold out in advance — “Every ticket — from special author events to general admission passes — has been claimed” — and walk-up tickets will not be available Saturday.

The day after the festival, Orlean will be at the Heathman Hotel for Live Wire’s Speakeasy Series. She will appear at noon Sunday with hosts Luke Burbank and Elena Passarello for brunch and conversation. Details and tickets are available here.

Oregon ArtsWatch talked recently with Orlean via email about her new book and her career.

I remember seeing a Tweet from you, some years ago now, that you were considering writing a craft book. Parts of Joyride read to me like a craft book, or at least a tutorial on how to become a distinguished nonfiction writer. Is the craft book inside Joyride?

Orlean: Yes, it definitely is. Rather than writing a book that was entirely instructive, I decided to give it more dimension, and explain the “why” of how I write rather than just the “how.”

You write about honing your writing’s sonic quality: how the writing sounds, its rhythm, and musicality. You specifically mention a love for lists. I’ve also noticed that your writing often uses alliteration, simile, and well-chosen adjectives. What is it about those devices that you find effective and appealing?

The challenge in any piece, or any book, is to keep the reader engaged. That happens not just on the level of the information you’re delivering but on the more subconscious level of how the writing itself engages you. That’s where the poetry of the writing matters: the way it sounds, even in your head, and the freshness of the language, the vividness of the description, the surprise of the sentences. That’s what keeps readers connected and pushing through a piece.

You write that you do not advocate for your story subjects. But you are adamant about getting readers to pay attention, to become entranced by subjects they may know nothing about or be initially repulsed by, to go on a journey from “ignorance to knowledge.” Isn’t that a kind of advocacy in and of itself?

Yes, it certainly is, but it’s more an advocacy for the importance of noticing, the value of learning about the world. When I say I don’t advocate, I am not writing an argument in support of my subjects; I’m writing an argument for learning about them. I wrote about children’s beauty pageants not to encourage people to participate in them, or even to judge whether they are a good or bad thing to do. I wrote the story because I felt it was important to learn about why they mean something to a lot of people and what they are really like. I left it to the reader to decide whether or not they like the idea of children competing in pageants.

When writing about Tonya Harding, you correctly observe that the mainstream media’s coverage of her was “a shallow and mostly sensational account.” You continue, “I hate reporting that relies on coded shorthand, that doesn’t really consider the nuance in a story, that supposes readers share an assumption about certain things.” Isn’t journalism chock-full of this type of reporting now? It seems to only be growing with the 24-hour news cycle and the machinations of the current presidential administration.

We get our information in smaller bits and with more coded language than ever before, so the chance of it being shallow and even inaccurate is greater than ever. There seems to be less space and attention for stories that grapple with nuance and even contradiction; we want things simple.

Your writing asks readers to understand, even empathize, with people and sub-cultures with whom they are likely completely unfamiliar but are still, as you write, “part of the American panorama.” We are lacking that understanding, grace, and empathy in our country right now. First, do you think the decline of journalism –– magazines, newspapers, etc. –– has contributed to this? If so, how so?

I don’t think you can distinguish the chicken from the egg: I’m afraid our appetite for empathy declined and media declined somewhat simultaneously, and it’s hard to figure out which influenced which. I don’t think you can say that media itself led to our current lack of empathy, but it has responded to it and maybe reinforced it. But so many other factors have contributed to the way the world is now, and the decline of media has very complex economic roots that grew out of the rise of the internet and the changing economy, quite separate from an emotional cause.

What should journalists be doing to reverse that tide? Are journalists writing enough about “the American panorama”? What role do you see literary journalism, specifically, playing in this?

Ideally, journalists, and especially literary journalists, would push harder to do stories that might engender a sense of appreciation and discovery about the broader American panorama. But in defense of individual writers, they can’t always control what stories they’re able to do. I hope, at least, that writers advocate loudly to do these other stories and do as much as they can to convince editors to let them tackle them.

While interviewing the daughter of Herbert Leonard, who became an important character in Rin Tin Tin, she gave you the key to her father’s storage unit, which ended up being full of archival material about Rin Tin Tin. What was it about your interview with Leonard’s daughter that compelled her to do this?

I honestly can’t say! I think she trusted me and had a sense that I really wanted to tell her father’s story as fully as I could, and I know she also wanted his story told. I think those factors outweighed whatever hesitation she might have had.

Who’s the quirkiest subject you’ve interviewed or researched: Charles Lummis or John Laroche? Or someone else?

I think Charles Lummis! Which is saying a lot, because I’ve certainly interviewed some quirky subjects.

For Rin Tin Tin, you had a “read this and weep” research task list. Do you have such a list right now? Please do not tell me Joyride is your last book.

Joyride is not my last book — I’m already starting on a new one, and it will undoubtedly generate another To Do list that will loom over me for years.

Source link