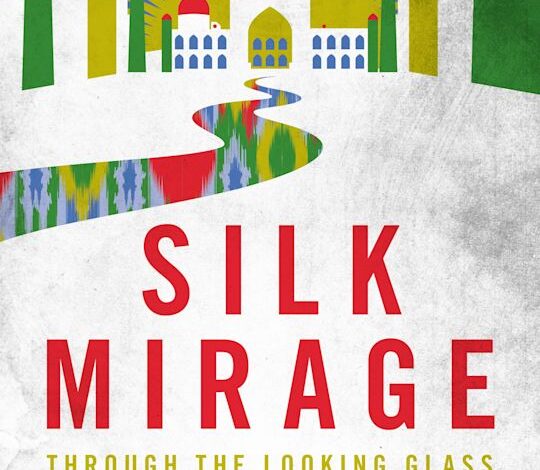

New Book Review: ‘Silk Mirage: Through the Looking Glass in Uzbekistan’ by Joanna Lillis

“Vibrant” and “brutal” are words that British journalist Joanna Lillis uses to describe Uzbekistan in her new book Silk Mirage: Through the Looking Glass in Uzbekistan, released this week through Bloomsbury. But they could just as easily be used to describe the book itself.

In her own words, Lillis, a Central Asia correspondent for The Economist and other media, set out to create “a portrait of Uzbekistan from independence to the modern-day, dipping into history to demonstrate where the country came from and how it got where it is today, and offer clues about where it is going.” She achieves this with a book that is clear-eyed and meticulously researched, detailing how Uzbekistan’s two 21st-century leaders, presidents Islam Karimov and Shavkat Mirziyoyev, have shaped the lives of Uzbekistan’s remarkable people.

The book opens with a summary of the paranoia and violence of the Karimov era (1989-2016), told through Lillis’ experience of having recently arrived in Tashkent in 2001. She lived in the country until 2005, and has spent a lot of time in Uzbekistan thereafter. While the western media that reported on Karimov’s death in 2016 speculated on a battle behind the scenes to succeed him, Silk Mirage is clear that power was always going to pass to Miziyoyev, who had been Karimov’s prime minister for the previous 14 years. Lillis does, though, memorably mention that “there may have been a fierce under-the-rug catfight.”

A recurring topic in Silk Mirage is the repression of the media in Uzbekistan, and local journalists’ need to self-censor and avoid uncomfortable issues. There is none of that in this absolutely fearless book. Lillis gives stark details of Karimov’s human rights abuses, particularly in accounts of the horrific Jaslyk prison. She also confronts his successor’s failure to eradicate some of the injustices in the present day.

When comparisons are made between life under Karimov, referred to as “Old Uzbekistan”, and the New Uzbekistan of Mirziyoyev, the progress towards democracy is described as a qualified success. The country now has a parliament with younger, more accountable deputies; however, “opposition” is still a dirty word, and the proliferation of new political parties is misleading.

Economic reforms have led to the previous official corruption and black market profiteering being replaced with a state that is friendlier to local businesses and foreign investors alike. That being said, there are still restrictions on citizens’ rights.

So, have Mirziyoyev’s plans for democracy and reforms been slowed down by systemic issues – the need for his government to first dismantle the dictatorship he inherited? Or is Karimov’s old ally too much of a product of Old Uzbekistan to fully stop the past from repeating? Lillis leaves the reader to decide for themself.

Silk Mirage dedicates chapters to events in Uzbekistan that have occasionally caught international attention. The last two decades have seen the authorities’ 2005 massacre of hundreds of people in the eastern city of Andijan, which was blamed on an ambiguous Islamist cult; outcries over forced labour and child labour in Uzbekistan’s cotton industry; the ecological crisis in the vanishing Aral Sea; and the (less publicised) violent riots in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic in Uzbekistan’s west, in 2022. On all of these issues, Lillis gives a comprehensive account, based on interviews with Uzbeks who have been witnesses to them.

Lillis also goes further back in the country’s history, to bring to life the city of Bukhara – and the Jadids, a group of enlightened Uzbeks who aligned with the Bolsheviks to play an influential role in the early Soviet Uzbek Republic. The Jadids were killed during Stalin’s purges in the 1930s, but their members are being rehabilitated under Mirziyoyev.

Another interesting parallel between the Old and New Uzbekistan is the role of each president’s daughter in public life. Silk Mirage tears down Gulnara Karimova for her vulgar excesses and dumbfounding corruption; by contrast, Saida Mirziyoyeva – aide to her father, but most visible through her leadership of Uzbekistan’s Art and Culture Development Foundation – is the ambassador that Karimova never was, and a champion of Uzbekistan’s creative industries.

For all that Karimov and Mirziyoyev loom large in Silk Mirage, it is the ordinary Uzbeks whose stories from this mesmerising country shine through. Through Lillis’ reporting, we meet the young tech entrepreneur Dildora Atadjanova, whose app helps Uzbek farmers to sell their crops to exporters. We also meet Agzam Turgunov, a former political prisoner who is now fighting to help others like him clear their names. And we are introduced to the former director of the State Art Museum of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, Marinika Babanazarova, who for years was the director of a vast collection of Karakalpak and other nonconformist art, better known as the Savitsky Museum. The story of the museum is an enthralling success story in its own right.

These are just three of the dozens of human stories that make Silk Mirage such a poignant read. Lillis has held a looking glass up to today’s Uzbekistan, and come back with a true reflection.

Source link