“We the Men” Author on the Importance of Remembrance and Resistance – Minnesota Women’s Press

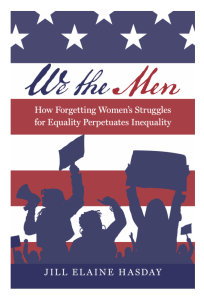

In her new book, We the Men: How Forgetting Women’s Struggles for Equality Perpetuates Inequality, University of Minnesota Law Professor Jill Hasday tracks how erasure has impeded feminist progress in American law and society.

Following our book review, we talked with Hasday about writing We the Men in the midst of the Dobbs decision, the importance of uplifting women’s history, and what the past has to teach us about resisting anti-feminist tides in the present. She indicated that launching the book during this Trump Administration has been unexpectedly fortuitous for book awareness because people “are looking for feminist conversation and inspiration in anti-feminist times.”

How did events that occurred during your writing process impact the book?

I worked on We the Men for about five years and was drafting chapters when the Supreme Court issued Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. I did not expect the Court to overrule Roe v. Wade in one fell swoop. But the Dobbs opinion ultimately felt very familiar to me.

By the time Dobbs leaked, I had already uncovered a century of judicial opinions that relied on rosy pronouncements about America’s commitment to sex equality to rationalize judgments maintaining or exacerbating inequality. Dobbs follows that strategy, repeatedly invoking overstated accounts of women’s advances to defend the Justices’ decision to leap backward and eliminate a constitutional right that women had held for generations. Dobbs is both one of the biggest feminist setbacks in American history and the latest manifestation of a very long judicial tradition.

We the Men is full of vibrant feminist anecdotes from American history. You’ve been sharing some of them on your X and Bluesky accounts as “on this day”-style posts.

We the Men is full of vibrant feminist anecdotes from American history. You’ve been sharing some of them on your X and Bluesky accounts as “on this day”-style posts.

Could you share a favorite anecdote?

One of my favorite stories in the book centers on Anne Davidow, a trailblazing attorney in Detroit. She represented four women who sued to block a 1945 Michigan law that prohibited women from bartending in cities with fifty thousand or more people, unless the woman was “the wife or daughter of the male owner” of the bar. The Michigan statute joined a wave of “anti-barmaid” legislation that the male-only bartenders’ union helped push through statehouses after Prohibition ended in 1933.

Challenging the constitutionality of Michigan’s law was an uphill battle. But Davidow was undaunted and appealed Goesaert v. Cleary (1948) all the way to the Supreme Court. She later reported that Justice Felix Frankfurter heckled her from the bench while informing her that “the days of chivalry aren’t over.” Presumably, Frankfurter either failed to recognize the irony or felt that Davidow’s effrontery in bringing this suit excused him from any obligation to act like a gentleman. Frankfurter wrote an opinion for the Court that dismissed Davidow’s arguments in less than three pages. Eventually, though, she had the last laugh. The Court overruled Frankfurter’s opinion in 1976.

In a recent talk at the University of Minnesota, you highlighted the ERA as a key legal effort in the ongoing work towards gender equality.

How hopeful are you about the ERA’s prospects?

The required thirty-eight states have ratified the ERA. But the last three ratifications came decades after the expiration of the seven-year ratification deadline that Congress inserted into the 1972 joint resolution sending the ERA to the states.

The crucial next step is to push federal lawmakers to act. Congress should either directly recognize the ERA as part of the Constitution, remove the ratification deadline, or ideally both. The Supreme Court has never denied recognition to a constitutional amendment that Congress accepts.

There is no single strategy that succeeds all the time. The key is to develop and pursue multiple strategies. Women are already doing that, which makes me hopeful about the ERA’s ultimate success.

In the face of erasure and anti-feminist momentum, what are the best counter-narratives and actions available to advocates?

Women’s rights and opportunities have expanded in myriad ways over time. But legal authorities have also sometimes reversed women’s hard-fought gains, and the persistence of women’s inequality remains a fault line running through American history. Progress remains in-progress, rather than complete.

My book illuminates how America’s dominant stories about itself shield inequality and encourage complacency by forgetting women’s struggles for equality and forgetting the work the nation still has to do. Recognizing those ongoing patterns can keep us alert and ready to respond when influential voices ignore women or wildly exaggerate American progress. We can look for opportunities to change minds and promote engagement.

We can also share an overriding lesson from the past.

The long history of women’s struggles for equality makes clear that progress is unlikely to be quick, easy, or achieved by anyone acting alone. Generations of women have learned that lesson and persisted nonetheless.

What do you hope to add to the conversation through this book?

The United States Constitution purports to speak for “We the People.” I wrote this book because too many of the stories that powerful Americans tell about law and society include only We the Men.

I wanted to uncover more of women’s history and to bring the long record of women’s struggles for equality into America’s dominant accounts about itself. Remembering women’s stories more often and more accurately can help the nation advance toward sex equality.

Source link