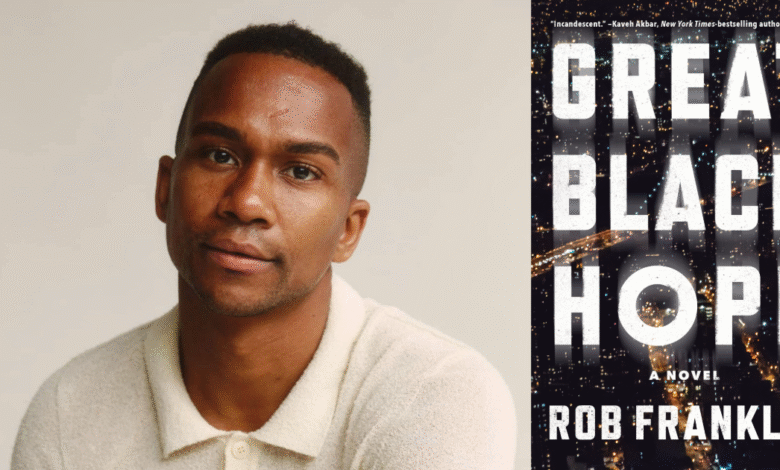

Indies Introduce Q&A with Rob Franklin

Rob Franklin is the author of Great Black Hope, a Winter/Spring 2025 Indies Introduce adult selection and June 2025 Indie Next List pick.

Kim Brock of Joseph-Beth Booksellers in Cincinnati, Ohio, served on the panel that selected Franklin’s book for Indies Introduce.

“Such a roller coaster of emotions in this stunning debut,” Brock said. “It makes you question class, privilege, race, and what it all means in American society. This book will make you question life, it will make you uncomfortable — most of all, it will pull you in until the very last page.”

Franklin sat down with Brock to discuss his debut title.

This is a transcript of their discussion. You can listen to the interview on the ABA podcast, BookED.

Kim Brock: Hi, I am Kim Brock. I am the adult book buyer at Joseph-Beth Booksellers, and I am happy to introduce Indies Introduce finalist Rob Franklin, author of Great Black Hope. How are you today, Rob?

Rob Franklin: I’m doing well, thanks Kim. Thanks so much for having me.

KB: Of course. This is one of my favorite books. This is one I was really rooting for when we were going through the selection. I really like this book.

Rob was born and raised in Atlanta [and is] a writer of fiction and poetry, a co-founder of Art for Black Lives, a Kimbilio Fiction Fellow, and finalist for the New England Review Emerging Writer Award. He has published work in New England Review, Prairie Schooner, and The Rumpus, among others. Franklin lives in Brooklyn, New York, and teaches writing at the School of Visual Arts. Great Black Hope is his first novel, and it goes on sale on June 10. Woo! How excited are you?

RF: I’m really excited! It’s totally overwhelming and exhilarating.

KB: Amazing. You’ve been a writer for a very long time. When did you know you wanted to write a novel and publish it for the world to read?

RF: As you mentioned, I came to writing fiction through poetry. I’ve written poetry since I was in high school. I forged my voice through poetry, but never had a clear sense of what that was working toward. It wasn’t until post college that I really started investing in fiction writing. I initially started working on a different novel — a novel set in Berlin. I’m very grateful to that project because I think it really set me on the path. It proved to me that I could write a novel, because I did finish a draft. It brought me to live in Berlin, and then ultimately, it led me to apply for grad school, which is where I started working on Great Black Hope. It’s been a roundabout path, but I started with a different novel, ended up going to grad school, having this idea, and pivoting. Once I started working on this, I knew I wanted it to be my debut.

KB: Excellent. For those of you who don’t know, Great Black Hope looks at race, class, and privilege, and what it is to be a Black person living on two sides of American culture. Where did the premise for the book come from? Where did you draw your ideas from?

RF: The seed of the idea was the protagonist Smith. I wrote the first pages that would become this idea on the day before my 26th birthday, sitting at home by my parents’ kitchen table in Atlanta. This was before I had moved to Berlin. I sat down without any agenda in mind, and just wrote five or six pages of material. It’s actually no longer in the book, but it was a character sketch of Smith, who, much like me, lived life split between worlds: the Southern Black bourgeoisie world of his parents and the downtown New York club scene. Then I put it away for a year. In grad school, when I was looking back at those pages, I realized I was still interested in writing about this character and about Black respectability politics, and how Black respectability politics can be a hindrance to understanding oneself or coming into one’s own.

Once I revisited those pages and themes, I started to realize that the subject of addiction was an interesting way to approach all of the cleavages between these different worlds. I had noticed in my own life how differently substance use and addiction are talked about in moneyed white spaces versus moneyed Black spaces. How stigmatized and pathologized the word “addict” feels when applied to a Black person. All of those ideas only came through the drafting process, but it really started with this character Smith.

KB: Smith felt so real to me, just because he was not perfect. He’s very complex, and there were flaws in him that you see in people and in yourself. How did you come up with him? What did you draw from to make him feel so 360? I was like, “I think I know you, you might be a cousin or something!”

RF: I’m so glad to hear that. You make a great point, he’s not perfect. I definitely wanted to avoid [that]. I think there can be an impulse for writers, when writing characters from marginalized backgrounds, to give them the moral upper hand or to not want to show them being super messy in essence.

KB: It happens! We are, it happens!

RF: Yeah! Even in Smith’s interactions with his close friend Carolyn — who’s a wealthy white woman from New York — you can see moments when he’s giving in to an impulse of feeling morally superior. He could actually be quite cruel. I wanted to have that texture that makes him feel like a real person.

In building that character, I pulled a lot from my own life. Smith, like me, is from Atlanta, elite and educated, and then he moves to New York. But in a lot of ways, he’s a more passive person than I am. That was a useful characteristic to give him, from a writerly perspective, because he gets to exist in all these rooms. Whether it’s one of his parents’ Christmas parties in Atlanta, a restaurant opening in New York, or a courtroom in Southampton, he’s a cipher for all of these different cultural cues and minor observations — almost anthropological observations — about that world. Because he is often standing there observing and being observed, and he’s very aware that he’s being observed, he’s a way to look into these different worlds. I liked having him be in certain scenes as more of an observer than a participant.

KB: Oftentimes, being a Black woman, I feel like you have to be a chameleon. You have to adapt. If you are in a courtroom, you’re one way in the courtroom. If you’re at the elite Black Christmas party, you’re a different thing. If you’re with friends, you’re a different way. Smith had that too, he had to be different people in different places. I feel like as Black people, we often are called upon to do that. Do you find that? Have you found that to be [true]?

RF: Absolutely. That is definitely a central attribute of Smith. That’s a better word than, you know, I use the word passive, but it’s more this chameleonic quality. It’s this changing — revealing parts of himself, withholding other parts of himself — based on the situation and what he thinks people want from him. And I think that has come at the expense of him totally understanding who he is and what he wants.

KB: Oh, 100%.

RF: That constant performance.

KB: Because the very act of code-switching, it’s like, when do I get to be me? I need to be this person here and this person there. When do I get to be me? Do I even know who I really am? I totally got that with Smith.

RF: Totally. That is definitely one of the things he’s up against in terms of coming-of-age, he’s gotten so good at the constant performance of self that he’s not sure who he is and who he wants to be.

KB: What other type of research did you do while writing this?

RF: There was definitely a lot of interpersonal research, talking to friends and family. For instance, talking to my grandmother. A lot of her life narrative I used to help build Gail, who’s Smith’s grandmother. She grew up on a sharecropping farm and becomes a lawyer. Her life story is a way to bring in the history of the war on drugs and all of the insidious ways it’s transformed itself but still remained. That came out of conversations with my grandmother. She told me about working as a lawyer during the Reagan administration when they were criminalizing drug possession and mandatory minimums were being introduced, and seeing the human impact of that within years.

I knew that history, but it gave me a personal way to introduce that into the narrative. It helped me understand how that could exist without feeling too didactic within a novel. A lot of the research for this project was a process of doing the reading and then figuring out how it could exist in narrative in an organic way.

With the middle section of the novel, which takes place in Atlanta, I was reading a bunch of 20th century Black scholarship on the condition of being Black, like Frantz Fanon, and Franklin Frazier, bell hooks, and Margo Jefferson. I initially had envisioned that middle section as very digressive and essayistic, having full essays on some of these texts that Smith is reading. Through many, many, many edits, I had to figure a way to dial it back and have those texts color the landscape and bring in those themes, without it feeling like I had just written a book of essays in the middle of the novel. I had to find the balance of doing the research, but not showing all of my research.

KB: You just mentioned Margo Jefferson, and she gave an excellent blurb for your book. How did that make you feel?

RF: Incredible. She was very much one of the spiritual predecessors for this book. Negroland was a book that I was reading and thinking about a lot as I wrote Great Black Hope.

KB: Excellent. That’s so wonderful. How are you going to celebrate the release day of your book?

RF: On the actual day, my launch event will be with McNally Jackson Books at PUBLIC Hotel in New York. It’s going to be great. It’ll be with my thesis advisor, Katie Kitamura, who has read so many drafts of this book. It’ll feel really full circle and lovely. I’m trying to get all of my friends to come to that first event. Then I go on tour for a bit. The idea is coming together still, but I’m thinking at the end of tour, I may throw a big party. Really cut loose.

KB: I feel like you need a party in Atlanta. You’re doing a thing in New York, you totally need a party in Atlanta.

RF: That’s a good point. I should. I’m going there the day before my launch, so I’m sure my parents will at least want to go to dinner or something. I’m excited.

KB: Rob, thank you so much. Everybody grab Great Black Hope, it is fantastic. You will want to talk about it. It will make you talk, which is important. Congratulations again on your book.

RF: Thank you so much, Kim.

KB: You’re welcome.

Great Black Hope by Rob Franklin (Summit Books, 9781668077436, Hardcover Fiction, $28.99) On Sale: 6/10/2025

Find out more about the author at robert-michael-franklin.com.

Source link