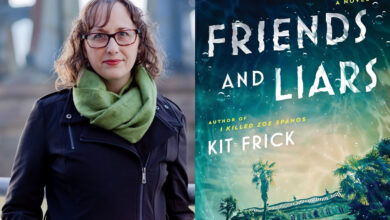

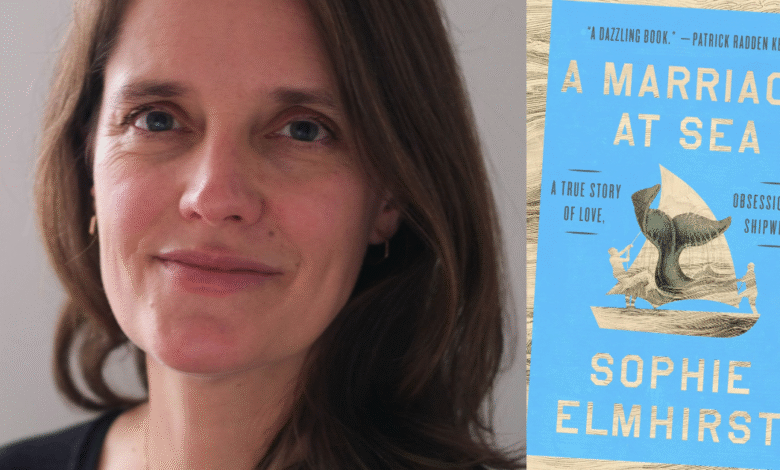

Indies Introduce Q&A with Sophie Elmhirst

Sophie Elmhirst is the author of A Marriage at Sea, a Summer/Fall 2025 Indies Introduce selection.

Stephen Sparks of Point Reyes Books in Point Reyes Station, California, served on the panel that selected Elmhirst’s book for Indies Introduce.

“It’s a rare accomplishment to write a shipwreck book that does something new, but Sophie Elmhirst manages just that with her enthralling debut, A Marriage at Sea,” said Sparks. “This portrait of a couple lost upon seas both literal and metaphorical will keep readers riveted till the last page.”

Elmhirst sat down with Sparks to discuss her debut title. This is a transcript of their discussion.

You can listen to the interview on the ABA podcast, BookEd.

Stephen Sparks: Hi, I’m Stephen Sparks, owner of Point Reyes Books in Northern California, and it’s a real pleasure to be here today with Sophie Elmhirst to talk about her Indies Introduce selection A Marriage at Sea. I’m going to rave about the book in a moment after introducing Sophie.

Sophie Elmhirst is an award-winning journalist who writes regularly for The Guardian Long Read and The Economist. Her work has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, and Harper’s Bazaar, among other places. She’s the winner of the British Press Award for Feature Writer of the Year and a Foreign Press Award. She lives in London, and A Marriage at Sea is her first book.

This was a book that, among the reading, stood out. It was so unique in its approach and its subject matter. It really cut through a lot of stereotypical lost-at-sea nautical adventure stories, because it does so much more that’s interesting, in a genre that — I imagine — is difficult. The book really cut across genres in a lot of ways.

Instead of me just raving, I want to ask you: how were you introduced to this story of Maurice and Marilyn? Did their story hook you as quickly as it did me, as a reader of your book?

Sophie Elmhirst: For sure. You don’t come across stories like this very often, especially ones that you feel like haven’t been told. I couldn’t believe, when I came across the story, that it wasn’t in common legend or the collective consciousness. It just seems strange to me that their story had been so forgotten. I’m a journalist in my day job so I’m always hunting for stories in different ways.

[It] was one of those profoundly lucky things that I was researching a particular piece on people trying to escape the land, and I just stumbled upon their story on a website devoted to castaways and shipwreck stories. Among all these images of grizzled looking lone men, there was this little photo of a man and a woman. She caught my eye because she felt quite unusual in that setting.When I dug a little deeper and found out more, I couldn’t believe it had been as forgotten as it had been. I guess it hooked me in — in the way I hope it hooks in readers, which is just the sheer extremity and drama and insanity of the situation in which they find themselves, adrift in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, their boat having sunk and been hit by a whale. The thing that made me think I could write a book was both of them as individuals and their relationship. Once I knew that there was enough material to excavate their relationship, that’s what made me think, “Oh, this could be the book I’d actually like to write.”

SS: I can imagine, as a journalist and a writer, that you felt like, “Wow, jackpot! I have stumbled upon something here.”

SE: It did feel like that. I don’t mind admitting that it felt like the jackpot. Rarely, you come across amazing stories, but then you find that there’s no material. Or you find that someone else has done it, or someone else is in the process of doing it. I knew that they’d written books, and those were easy to come by, but I have hardly met anyone that remembered them or had read their books. (I have met more people now that my book is out in the world.) It just felt incredibly lucky.

And then to find this wealth of material just beneath the surface, not just the things that they’d written, but media coverage of their rescue, surviving friends and family, and diaries and photographs… There was just so much to draw on and that was the thing that felt incredibly fortunate, I think, because that’s not always the case.

SS: Yeah! Among many things I found intriguing in the book, are both the adventure — being lost at sea and that harrowing travail — but also the way that you bring both their personal and interpersonal dynamics alive. This is as much a story of a marriage and a relationship and how we deal with people, as it is a straightforward nautical tale. What was it about their dynamic that really hooked you in as well?

SE: They were such a marriage of contrast, in a way. As I found out more about them and talked to people about them, [I felt] the sense of almost mystification from people who knew and loved them well. That was fascinating to me, that even the people nearest to them couldn’t quite understand their relationship, and so that made me want to understand it all the more.

The way Maurice does analyze their relationship — often to his own detriment — he’ll say that it was really Marilyn that got him through, and that supported him, certainly when they’re drifting around on the life raft. They were such extraordinarily different people in the way they related to the world and other people. He was this awkward and lonely man before he met her, living quite a dislocated life, and she was this livewire and such a compelling, energetic, positive presence. [There’s] something about how a marriage like that works, then putting that marriage in this extreme scenario, to the ultimate test.

There was something I found to be universal about that. The best stories are ones that are highly specific and, in this case, very extreme, but that have some universal resonance. We all know what it is to hit crunch points or to have [to] face crises with a partner, or with a friend, or a significant other, and what that does to a relationship, what that does to you as an individual, what it reveals to you about yourself, but also about that other person. It just felt like an incredibly rich field of material.

SS: It’s an experiment, in a way. Even in relationships, there’s a dynamic that changes, but you put them in heightened circumstances and let’s see what happens. And this book is “let’s see what happens.” It really shows in that way.

SE: Yeah, totally.

SS: A story about anyone being lost at sea is inherently compelling because I think a lot of us can extrapolate and imagine “what would it be like to be there?” I imagine, then, [that] writing it is somewhat difficult, because you only have so much to work with. You do something really interesting in the book.

I wonder how you thought through the craft component to maintain the tension in the book. Some of it is inherently there, as you said, between [the] two and the circumstances. The book maintains this taut narrative tension throughout, and that is so compelling as a reader.

SE: Oh, that’s good to know! I don’t know how much is conscious [or] how much is instinct. There was one way of telling the story which would have been the more obvious way (and, certainly according to some of the comments on the internet, is possibly the way that they would have preferred) which is just them adrift, and [then] you end with the rescue, and it’s a happy ending. Job done.

That was never the story I wanted to tell; I did want to complicate it and extend it and give a sense of their whole lives, from childhood, [to] them meeting, [and] right to the end of their lives, without losing that tension and that sense of propulsion. I read more fiction than nonfiction, and I wanted to try (and there’s plenty of nonfiction that has done this already and that was an inspiration to me) and write a piece of nonfiction that had some of those great devices and attributes of good fiction — which is a sense of narrative propulsion, a sense of character, of interiority, of going with people through something, and reaching a different point with them. Sometimes in nonfiction, you have a sense of the authors on high, or it being a point of argument. I just want it to be a story, and to try and marshal the material I had into story form.

In terms of how I did that, a lot of that was omission; not including things and trying not to be distracted by too many things. There’s so many rabbit holes and tunnels I could have gone down — and did go down in the research of — [such as] that part of the ocean, or sperm whales [and] how they live, all sorts of stuff. You could have easily crowded it out, and I tried to be quite disciplined about keeping the focus quite narrow and driven by the characters themselves. That was the intention, in any case.

SS: It succeeds! The close narration actually muddles things a bit. When you read a book from someone whose day job is as a journalist, you think you’re going to get one narrative. Then you read this and it feels like it’s somewhere between fact and fiction. You’re marshaling these facts for this end, but the craft component, to me, was really one of the more compelling parts. And that leads to my next question.

The traditional tropes of these stories are male heavy [as] largely men were the ones who went to sea. But Marilyn is such a strong character. Was there any conscious part of your process where you thought “I’m going to subvert some of these tropes of this narrative,” or did that just come about because of who she was and what the story was? Or maybe it’s a mix of the two?

SE: I think it’s a mix of the two. I know the moment I knew I wanted to try and write it as a book, as opposed to just as a piece. I didn’t know what I was going to do with it [at the time] but it was [after] finding the letters that he wrote later in life which he self-published.

A lot of those are just going over the same material and going over their travels and journeys, but it’s after she has passed away, and he’s grief stricken, and lonely, and introspective. He is tearing strips off himself, he has this depressive cast of mind, and he’s going round and round in circles and regretting things and regretting how he wasn’t. It was just suddenly on the page, getting the sense of a man who was so at odds with a swashbuckling hero that you might get in a survival or disaster narrative.

The more I read, the more I uncovered, the more this was corroborated. This sense of a man who was really at odds with himself and was such an anti-hero. I get this sense from readers sometimes [that he] drives people crazy as well — he’s an infuriating man in lots of ways, but that made me all the more fond of him and more interested in him. I think anything that complicates someone or complicates a picture is a good thing. As a writer you want human complexity, or you want the challenge of that, [you want to do] justice to that.

And then, of course, he perfectly allows her to rise to the challenge and to be the real hero of the story. He’s the first one to credit her with that status, he’s the one that will always say that she was the one that kept them going, kept them alive. She quite effortlessly was the driving force, not just on the boat or on the raft, but in all of their lives. That was fruitful in its own way, because it became a very interesting thing to think about, and a sad thing to think about, but interesting in [examining] how relationships work, and how we depend on each other, and the degree to which you’re propped up by someone, or you’re propping up someone, and what you do when that that prop is removed. It all felt like interesting territory.

SS: It really is, it’s so fruitful. There were moments reading the book where I would shake my head and think “I am such a Maurice.”

SE: Me too, me too! I hate to say it, but I got pretty down on myself in the process of writing.

SS: I can imagine!

SE: Wishing I was more like Marilyn.

SS: Okay, I’m not alone in this. I definitely had moments where I was like, “Oh God. I know I would crumble in the same exact way.”

You’ve done such a compelling job already [of] pitching this book to us and telling us the origin and everything. And I hope my enthusiasm is also conveying that to my fellow booksellers; I know that it did on the panel discussions for Indies Introduce.

If you were a bookseller in a bookstore and someone’s asking for a recommendation, and this book is sitting on the table next to [you], what is your quick elevator pitch? What is your handsell for this book?

SE: I should say my first ever job was as an indie bookseller when I was eighteen or nineteen years old. It was only for about six months, but I have brief experience. I think I’d say, “This is, on the surface, one of the most insane and compelling adventure and survival stories you’ll read, but it hopefully offers more than that as well. Beneath the surface of that you’ll find a deeply intimate world of a relationship. There’s much to discover there.”

SS: I would agree, and I would pick up the book after hearing you tell me that. It works on the literal level because it is a true story that happened. I think we’ve all felt at sea, both personally and in our relationships. The figurative level, [and] the meta way that it works, is also so compelling and really well done.

I feel vicariously joyful that this book is getting this recognition already before it’s even been published here [in the United States] and I know your editor at Riverhead, who was so enthused about this, and so [there is] a lot of joy going around. This book is going to be one that’s going to find readers, and it’s up to us as booksellers to make sure we get this into people’s hands. Thank you for it.

SE: Thank you for all your efforts in doing that, I appreciate it a huge amount.

A Marriage at Sea by Sophie Elmhirst (Riverhead Books, 9780593854280, Hardcover, Biography, $28, On Sale: 7/8/2025)

Find out more about the author at sophieelmhirst.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.

Source link