Indies Introduce Q&A with Jemimah Wei

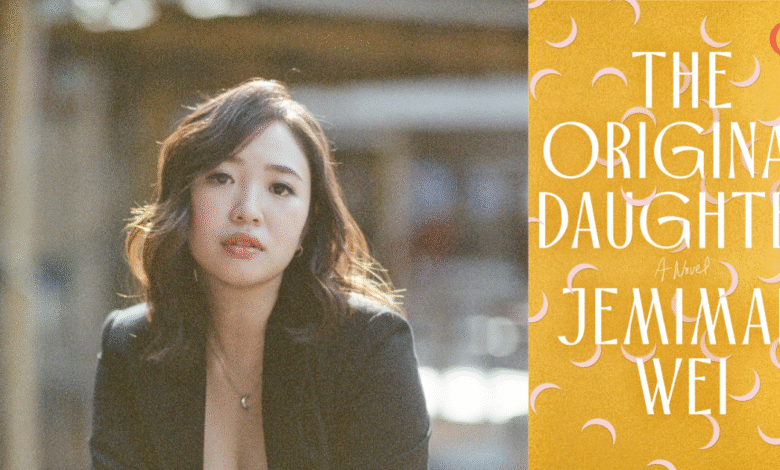

Jemimah Wei is the author of The Original Daughter, a Winter/Spring 2025 Indies Introduce adult selection and May 2025 Indie Next List pick.

Dave Suiter of pages: a bookstore in Manhattan Beach, California, served on the bookseller committee that selected Wei’s book for Indies Introduce.

“Jemimah Wei crafts a beautiful story in The Original Daughter, exploring a woman’s relentless determination to succeed despite her efforts not yielding the anticipated results,” said Suiter. “It’s a soul-searching narrative about a woman who does everything right to achieve greatness but finds herself with little to show for it. Wei contrasts her protagonist’s journey with that of her sister, whose hard work pays off in the ways the narrator wishes her own did. The story is rich with complex family dynamics, a complicated mother-daughter relationship, an estranged father, and a one-sided sibling rivalry. Wei’s portrayal of these ideas adds depth and weight to this compelling tale.”

Wei sat down with Suiter to discuss her debit title. This is a transcript of their discussion.

You can listen to the interview on the ABA podcast, BookED.

Dave Suiter: Hello. My name is Dave Suiter, with pages: a bookstore Manhattan Beach, California, and today, I am speaking with debut author Jemimah Wei about her novel The Original Daughter, which will be released on May 6, 2025. Jemimah Wei was born and raised in Singapore, and is currently a 2022–2024 Stegner Fellow at Stanford University. She’s a recipient of fellowships, scholarships, and awards from Columbia University, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Singapore’s National Arts Council and more. Her fiction has been published in Guernica, Narrative, and Nimrod, among other publications. She earned her MFA at Columbia University, has worked as a host for various broadcasts and digital channels, and has written and produced short films and travel guides for brands like Linnaeus, Airbnb, and Nikon.

Jemimah, I’m so excited to be speaking with you today. We’ve interacted before on Instagram and talked once in the middle of the night, but The Original Daughter is one of those books that just makes me so happy to be a bookseller. It’s going to be so much fun when it comes out, to be selling it to all the customers at pages. And I’m so excited for you.

Jemimah Wei: Thank you so much, Dave. I am so happy to talk to you today. And you know, talking to readers and booksellers — I’m starting to learn that this is part of what makes me love being a writer as well. I just remember so fondly the moment you called me with the news of Indies Introduce, and I’ve been so moved by your support of the book, and those were such lovely words. Thank you so much. I’m so happy to be here.

DS: You’re welcome. So, The Original Daughter explores themes of identity, belonging, and family expectations that are driven by a cultural setting. It’s not just the relation between the two sisters who are the stars of the book — Genevieve and Erin — but also their relationship with their parents and their grandparents. What inspired you tell this particular story and how much was influenced by your own experiences?

JW: When it comes to the question of how much is influenced by my own experience, I always think to myself: they have a family. I have a family. I have feelings for my family. They have feelings about their family. So it’s less the particulars of those things, and more about how I negotiate my relationships through my life. Relationships are really important to me.

About a decade ago, as there was this increasing conversation globally on boundaries and self-love and wellness — all of which I co-sign, I think boundaries are important — I started thinking more and more about how that had an impact on our formation of a self, especially as we try to navigate identity, individualism, and intimacy. Because where I come from, when you love somebody, you’re all up in their business. Even if that makes you want to kind of die, you know? And that, to me, is a really interesting dynamic.

As I’m sure you can tell, I’m a bit of a yapper. I love to talk. And when you talk non-stop, you really notice the silences or holes in stories. Growing up, I kept coming up against these silences around origins, around absences in family. I realized very quickly growing up, that it was very common — not just in my extended family, but in the families around me — for children to be given away and taken in. It’s not something people really talk about, but it was extremely common just a generation or two ago. To me, in the different drafts of this book, one thing that stayed constant was this idea of a returned sibling. Very early it was a returned brother, but it finally landed on the sister, and it went from there.

DS: It’s that relationship that Genevieve and Erin have that really drives that book. Erin just shows up, a fully-formed sister at the age of eight, and turns everybody’s life upside down. But I felt like it was a one-sided rivalry with Genevieve, who was so burdened by her ambition. Erin was just thrilled to be following in Genevieve’s footsteps — the younger sister looking up to her big sister. How did the difference in their identities really drive them and make them so different, even when they were so close?

JW: One really interesting thing I wrangled with was choosing the perspective. This is a first-person book, and you’re very immersed in Genevieve’s perspective. Erin is dropped into her life fully-formed at the age of seven, but she isn’t fully formed. She’s a seven-year-old child. I think that’s one thing that Genevieve really can’t get around, this idea of seeing past herself and her vision of Erin. That limits the generosity she can have with her sister and with herself as well.

I do think that there is this idea of doubling or over-identification that can come with immense, intense closeness that we often find in girlhood. (Maybe boyhood, too. I don’t know, because I’m not a boy.) At that age, you become so close to somebody you want to be almost the same person, and as you try to form your individuality, there’s bound to be friction. There’s bound to be things that you don’t like about each other and that you are surprised that the other person has access to that you don’t — even in terms of our interiority. Learning to navigate that relationship or expand ourselves, to see that is not necessarily the be all and end all, it’s an ongoing journey. For me, it’s not so much about Genevieve being burdened by ambition — though she is that as well. It’s about her learning to be a self while negotiating her idea of a self.

One of my very early notes for the novel was that these two sisters really love each other, but they are the absolute worst people to be around each other, because they bring out the worst parts of themselves, or they force themselves to confront their worst impulses. So generally, her relationship with Erin forces her to confront the things that she’d rather not see about herself. She would like to have this image of herself that she’s a good sister, she’s very loving, she’s there for the other person. But the truth is she, like many of us, is petty, competitive, and wants to win. You can choose to walk away from that relationship and not confront that, and maybe it’s an easier life, but her love for her sister causes her to stay in that relationship.

For me, the question was: What can a relationship and love endure? Instead of having that generosity of self to expand her own vision and think, “Okay, this is something about myself that I don’t love. How can I work to encompass that and not have to negate who I am or negate my love for my sister?” She chooses more disruptive paths.

Erin, on the flip side, has the opposite experience. She’s coming into this family. She doesn’t want to be left behind. She’s been abandoned once before at a very young age, in an experience that’s extremely traumatizing when you’re not fully able to understand what’s happening to you. Erin really needs to learn how to not self-abandon in the face of conflict. To put it in a different way, she’s a bit of a people pleaser. She will do anything to keep the people that she loves in her life, even at her own expense. These two characters, when you put them together, are both the best people for each other in that they love each other, and the worst because they bring out each other’s worst impulses.

DS: Wow. It’s incredible how you can describe that, because the relationship was just so good and the characters were so fully formed. I really enjoyed both of them throughout the story.

JW: Oh, thank you. I mean, I lived with them for nine years. I’m glad they’re out there, and other people can have them now.

DS: Well, thank you for both of them! They’re wonderful. One of the things that was also great was the setting in Singapore, and then later when they went to New Zealand. It plays such a significant role in the story. What was your approach to building that world, and what aspects of the place and culture were important for you to capture?

JW: Those two things for me were different. Singapore is where I was born and raised. It’s where I grew up. There are not many of us Singaporean writers. There are more now, but we’re still a massive minority. (And that’s just a function of statistics; we’re a tiny country.) It was important to me to capture the very specific details of the lives of these people — the flowers they rip off the branches and eat, the noodle shop they like, the habits, the games they play — because I don’t think these are things that make it into bigger, more glitzy narratives. I think that if we don’t capture it right now in print, immortalize it in a separate object, the country will change, and we will lose these things very quickly to the unreliability of memory. Then they’ll get painted over with nostalgia, which is great, but not quite accurate.

This is something I experienced greatly while growing up. Doing research for this book was so hard, because Singapore changes so quickly that to fact check something that exists during this specific year, it’s 1,000,001 emails to everybody I know and their mother! Did this exist back then? Or had it already been determined inefficient and therefore scrapped in the country? So this sense of velocity that I grew up with gave me a sense of urgency. I really, really want to capture these things before they we lose them, and we will lose them. I know that.

For New Zealand, I was really interested in this idea of the Singaporean abroad, because as a country, we’re small. We don’t have a countryside. A lot of countries, you want to get away from the city, you go away. We don’t have an “away” to go to because we’re tiny. We’re a city-state. You go any further and you end up in the ocean. So, a lot of Singaporeans want to leave. They want to explore the world. And there are very few ways to get out, right? You have to have money, you have to get a scholarship, you have to get a get a great job, or marry out. A lot of that is predicated on different kinds of privilege: intellectual privilege, family privilege. I really wanted to know how a girl who felt like she’s at the her absolute limits [could] find a way to leave. So I led her to New Zealand.

Part of that really was working backwards from what I needed the story to do. I work around a really specific geographical event that happens in New Zealand, that does happen in reality. I actually saved up to go for a research trip to Christchurch, in 2016 or ‘17. I just walked around, did research on the geographical situation there, talked to anybody who was willing to talk to me, and put all of that into research into the novel. That was interesting to me, because I went in thinking to myself, “this is going to be the other location in my book.” But when I went there, I learned life influences art, and my vision of what the book could do changed.

Even though Christchurch is an island and Singapore is an island, they’re so different. There’s this sense of timelessness in Christchurch that I experienced as an outsider. And there’s a sense of immense velocity in Singapore. It could be my biases confirming what I wanted to happen since I’d already started working on this part of the book, but I was like, “this is the perfect other country to put in my book.” This sense of having a different time chromosome to a different city or different experience changed the way the prose moved as I revised and wrote, and I really had to discover that as I went along in the writing.

DS: It’s stunning how you can really feel the humidity of Singapore, and then the devastation that comes in New Zealand. The setup and her life there, from the little house that she’s living in, it’s just so fascinating. It made me feel like I was there, and it was really great.

JW: Thank you.

DS: Now, your creativity spans multiple disciplines, from writing, academia, media, doing films — similar to both Genevieve and Erin! How did this shape your approach to their characters, and how did it influence the way you crafted this novel?

JW: One thing I think I really share with these characters is this sense of suffocation and survival. Growing up with this great desire to have a different life. Part of that is being young — well, I’m not young anymore. I started the book over a decade ago, having this sense that I wish there were more that I could do, and having no agency over my life. When you’re young, the external circumstances, be they the machinations of adults or just the life you’re bought into, make you feel like there is no way forward. You have no control. There was this great desire to have a life where I’m not just trying to survive, but thriving. I don’t think this is specific to Singapore, even though we have an abundance of pressure cooker kids. I see this desperation across any modern capitalist society.

With these characters, I thought to myself: what are the different ways you can get out of this situation? When I was young, there was no internet. There was no YouTube or Google. We were just flirting with this idea of something you dial up to, and when you used the internet, your parents couldn’t get on the phone. Then suddenly, very quickly, things changed. The advent of social media, to me, was so interesting, because suddenly it felt like there was this new frontier. There was this new whole industry — totally untapped, because it was brand new — where you didn’t seem to need any inherited privileges to enter. You just needed an internet connection and a really niche interest. If you like shoelaces, for example, somebody on internet is also going to like shoelaces, and you could make a whole living talking about shoelaces. But that may not be true in your everyday life. You might grow up and be like, “I like shoelaces,” and your classmates will be like, “Okay, we don’t care. We like soccer.”

That was a really fertile time, and there was so much tentativeness around what like commercialization would mean for that. Very quickly it did become commercialized. Within a decade now, the internet is mega. All the brands are everywhere. You do feel a sense of skepticism now, but back then, it didn’t feel that way. I really wanted to put that into the book. You mentioned my own experience. I had a long career as a presenter. I got my start because I was scouted and asked to do a reality TV show. I got really lucky, because I was really young, and it could have been a really bad experience. But from the start, I was scouted by a woman and I had really strong female mentors in the industry. Even though it was very difficult at a young age to suddenly be perceived so widely, I was always very protected, and I had a good relationship with my team. I don’t think that’s necessarily always true.

I grew up without a TV, so I didn’t have that sense of the media in my head all the time. Media messaging became very new to me in my early twenties, which is crazy! I think I was a little more equipped to deal with it because it was a sudden, big switch. It wasn’t like I was gradually cooked in it. I really wanted to know what it could have been like in a different world, where I didn’t have those systems of support, where life was different. I think part of the wonder of art and literature is being able to take certain questions that you have and really push them to extreme limits. That’s what I tried to do with this book.

DS: Amazing. You really did it. We talked about it a little bit, how long of a creative process this was for you — you said 10 years. You even traveled to New Zealand and did the research. What was the most surprising or challenging part of writing the book, and how did the story evolve from your initial idea?

JW: It’s gonna sound like a cheesy answer — I’m just amazed that I have a book. I’m surprised that I finished it. It took so long. When I started it, it was contemporary, and now people refer to as historical, which is very horrifying to me. Recently somebody was like, “You wrote a historical novel, right?” I was like, “Absolutely not.” But maybe it’s true, I don’t know.

I grew up in Singapore, and my vision of what it could look like to be a writer was very different. I thought I would just try and finish a book, maybe self-publish, or look for someone to take me. My life was greatly changed by opportunities that came up around how to make money online, and scholarships and how to work the academic system — basically by studying 24/7. That to me, was a big pivot that opened up my world to what being a writer could look like as a life, not just something you do in the middle of the night when everybody else is asleep. That was such a surprise, but it’s a surprise to nobody else, because other people have done it. Other people have written books that are out in bookstores. But that, to me, was a great surprise.

In terms of how the story evolved, I keep thinking because I spent so long on it and I did so many revisions, [it] has changed so much. But I went back and looked at earlier writing, all the way back from 2014, and it’s kind of crazy, but all the bones of the story were there. Everything that was going to happen was already in those early drafts, all those early pieces of writing. I just had to catch up. I had to figure out the best way to tell the story, plot-wise, what situations to put them in, and honestly, how to become a better writer so I could handle the vision for the book. In 2014 I was just, I was not a…I was not there craft-wise. I was not able to do that. So, I had to catch up.

DS: And you said, I mean, originally it was, there was a brother?

JW: Yeah, nuts!

DS: Was Erin going to be the brother?

JW: No, no, no, no, no. I had this idea of, basically, a return sibling. Initially I was experimenting with the idea of a brother that was given away and now comes back, but then the dynamics would be different, right? For example, they would not be able to share a bed with their mom, which they do in the book. And some of those choices are made situationally. You’re thinking: what situations can I put my characters in that would best bring out these questions I really want to have answered? I don’t really want to answer the question of a brother, sister, and mom sleeping in a bed together. That’s not my artistic concern right now.

Other things that changed were… I mean, they feel really big when I’m going through them, but now in hindsight, I can see that the book didn’t change that much vision wise. A really big thing happens in the third quarter of the book, right? This novel was in first person the whole way, and in one draft, I switched to third person after that happened, because at some point a person breaks, and you disassociate completely. I wanted to see that reflected in the craft. That did not work, and it took a whole year of trying that out. I was like, never mind, back to first person. But things like that, that’s why it took so long. It was trying all kinds of ways to make the story fit the best.

DS: Wonderful. Now that The Original Daughter is out in the world, what do you hope readers take away from it? And what’s next for you as a writer?

JW: I’ve always thought about this novel as a love story, but the most unromantic love story ever. That ends up being the question I always come back to when people read the book and talk to me about it. I really hope that people interrogate the particulars of their life as they’re going through it, because we live in a very accelerated world. I don’t think we are meant to live at this pace, actually. When we live in such a ruthlessly efficient world, the things that go are the things that don’t make sense on paper, and a lot of those are relationships that we can’t quite justify in the moment.

I didn’t go into this book thinking you must stay with the people you love, or you must leave the people you love if they cross certain boundaries. But I do think that we need to think about it and not just have knee-jerk reactions based on the way our society moves so quickly. The thing I’ve landed on is that interrogating your own life is working to understand it. It’s a way of owning and reclaiming time, because we can do a lot of things, but we can’t go back in time. I do think love and relationships are there in our lives if we want them, and if we find it worthy to work on those things.

As far as what’s next for me as a writer, I have been lying down a lot after finishing this book and taking a lot of naps because it was a tiring nine years! I just started working on something new, which I don’t want to talk too much about, because I’m scared of scaring it off. But I do feel really grateful to The Original Daughter, because I feel like finishing it gifted me a new stage of relationship to my art. I think that when you work on one debut for a really, really long time, your identity as an artist can feel co-dependent with the work. It can feel like if the work doesn’t happen, you’re not an artist. What you’re working on is not worthy. But now finishing the book, I do feel this great freedom to go in different directions, to develop certain questions I have a little bit more. I feel totally free! Which is kind of great, because I did feel like I was living in this world for a really, really long time.

DS: That’s amazing. It’s been just so wonderful speaking with you today, getting your insights on such a great book and your creative process and the whole thing. I am very excited to read this book again. Cannot wait to get my hands on the hardback copy of it. It comes out May 6. And thank you so much for your time today!

JW: Dave, thank you so much. This is so wonderful.

The Original Daughter by Jemimah Wei (Doubleday, 9780385551014, Hardcover Fiction, $30) On Sale: 5/6/2025

Find out more about the author at jemmawei.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.

Source link