Inside the absurd world of advertising with author Aurora Stewart de Peña

Listen to this article

Estimated 6 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.

The earliest advertisement Aurora Stewart de Peña remembers seeing is a My Little Pony commercial featuring kids brushing pony hair in the sunlight of a perfectly manicured backyard.

What appealed to her was the “endless unstructured time that they had to play and imagine,” the Toronto writer said on Bookends with Mattea Roach.

While the product, My Little Pony, is on display, it’s more than that that makes people want to buy it.

“You are selling a perspective, you’re selling a world,” she said.

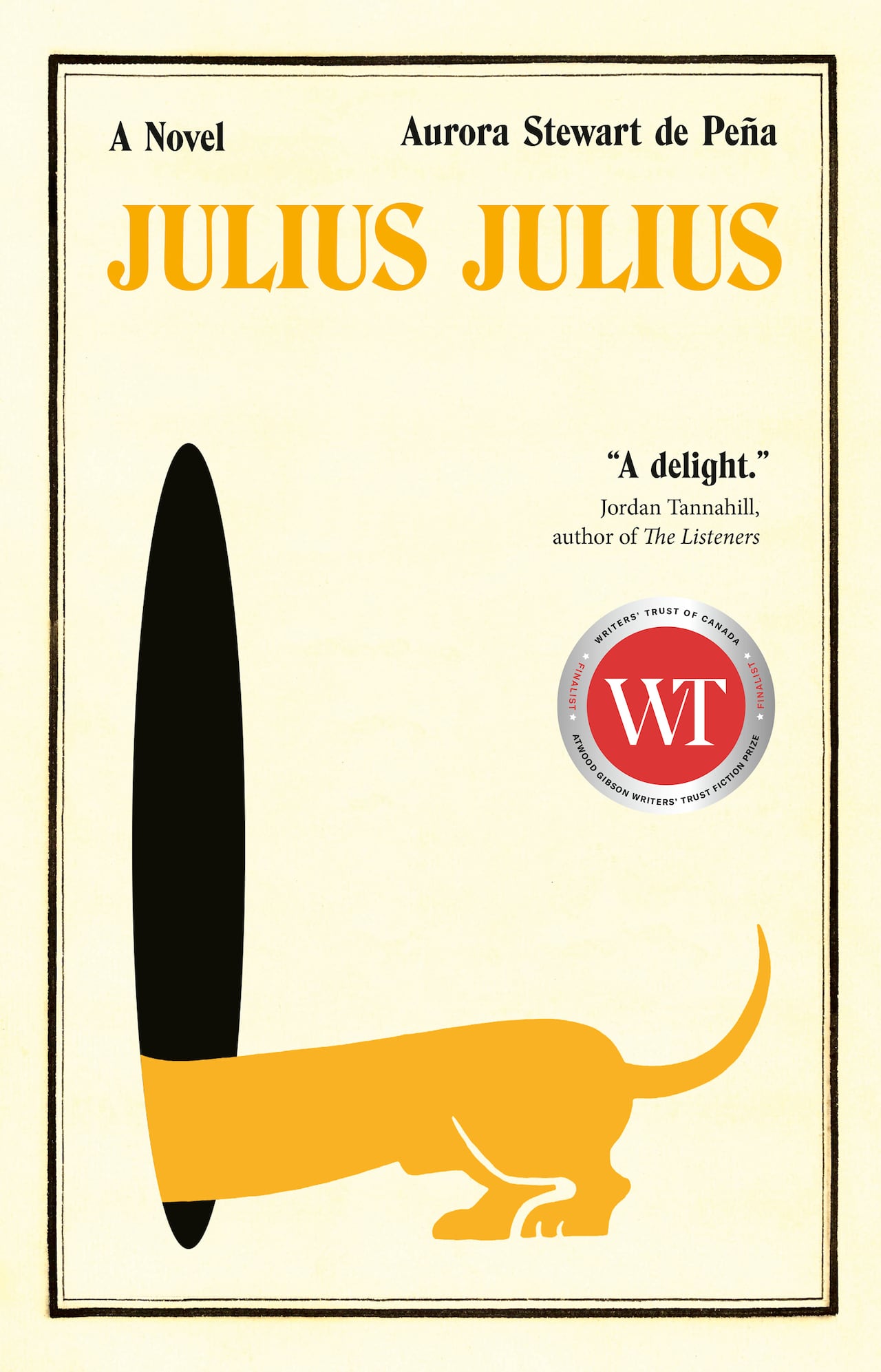

Now, after years working in advertising, Toronto writer Stewart de Peña crafted a satirical novel, Julius Julius, about what it really means to stoke desire, giving readers an inside look into the world’s oldest advertising agency.

At the mythical agency, ghosts roam the boardrooms and an unending lineage of blonde wiener dogs sleep under the office desks. The novel examines the realities of the industry through the perspectives of three people over three different time periods.

It’s also nominated for the Writers’ Trust Atwood Gibson Prize for fiction.

Stewart de Peña joined Roach on Bookends to discuss the world of advertising and its absurd realities.

Mattea Roach: This novel has a lot of the trappings of the ad world. But there are also these magical realist and absurdist elements to it. Why did you want to bring this magical realist style into the world of advertising?

Aurora Stewart de Peña: I think often the work feels absurd and gets into the dream space.

When you work in advertising, you are often working extremely long hours. You are getting to know people so intensely and you are thinking, at least in the line of work that I was doing, very conceptually. And so it gives way to some, I would say, explosions of the subconscious.

It gives way to some explosions of the subconscious.– Aurora Stewart de Peña

I was also thinking about the extremity of feeling that I had while working in advertising and the necessity that I keep it under wraps and appear to be a responsible employee of a big corporation. And so those elements have to do with emotional outputs that I felt while I was working in that world.

In Julius Julius, we are dropped into the lives of three different characters working there and they’re all at different stages of their career. We’re not going back and forth between the characters. We hear them in order. Why did you want to structure the novel in this way?

It’s set up the way that you would do that, you would create an ad. So that’s one reason.

The first person is a strategist, the second is a creative director. So the strategist would brief the creative director and the account person would maintain the relationship with the client. Often an account person is present the whole way through, but in this case it’s an intern and so that person comes in later.

I often felt very siloed in my work — and this is maybe just a drawback of me as an employee, as a person who tends to like to do things on their own, but it can feel very lonely working in advertising. And so I wanted to zero in on these people for whom work is everything and show the obsession that can often grow and how lonely that obsession feels and how isolating it can feel.

I want to dive into the first character we meet in this novel, the senior brand anthropologist. She has some conflicting views about working in advertising. Can you tell me a little bit more about that and why she feels this sense of conflict at this stage of her career and in the role she’s in?

This character in particular is at a point where she is making a decision about whether what she is doing is good and useful or not, because she has this drive to be part of culture and she has this drive to affect culture and she has this idea that affecting culture is a good and useful thing to do and and a legacy that she wants to have.

At the same time, as she gets deeper into her work, she becomes aware that there are systems that she’s part of that create harm. She becomes aware that the workplace that she’s in is ambivalent to the harm that is being caused to her.

So I think that the anxiety that she has runs as a current throughout that full first portion and is about her coming to understand that something she had been determined to be optimistic about is not necessarily worthy of that optimism.

There’s almost this angle of like we should not be too hard on ourselves for buying into the dream that ads sell because it is very powerful. How do you feel about being advertised to?

I’ve heard that take on this before, you know, “Don’t be too hard on yourself.” But what I wanted to demonstrate was the level of work and care and thought that goes into someone making an ad.

Often, when people say I hate being sold to, I think they are thinking of the invasive feeling that comes from someone attempting to push at your identity and saying, “Don’t you wish you were like this? Shouldn’t you be like this? Shouldn’t you care about this?”

I was not hoping that the take away would be, “Go easy on yourself. This is a very seductive world.”

But what I did hope that people would come away from it thinking about was just how expansive and considered and insidious and manipulative this world can be.

Bookends with Mattea Roach27:31A fictional ad agency — and its very real ghosts

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. It was produced by Liv Pasquarelli.

Source link