‘Once you’ve had a rocky and unsafe childhood, you can’t trust safety’: Arundhati Roy | Books and Literature News

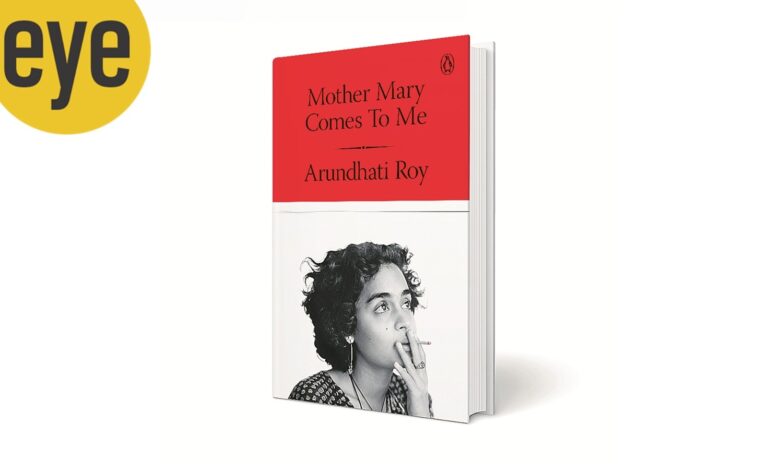

“I left my mother not because I didn’t love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her,” writes Arundhati Roy, 63, in Mother Mary Comes to Me (Penguin Hamish Hamilton), a memoir that traces the arc of her mother Mary Roy’s extraordinary professional life — as the founder of the Pallikoodam School in Kerala and a pioneering women’s rights activist — alongside her complicated personal journey as a single parent.

Where does a writer turn to for inspiration? Is it to the half-healed scabs on the heart that conceal years of hurt; to the filial urge to salvage tenderness from disaffection, or to the disorienting realisation of being unmoored when others seem to have anchors that hold them steady? In Mother Mary Comes to Me, the Booker Prize-winning author and political essayist turns inward to probe the often tempestuous terrain of the domestic to understand the defiance, idealism and deep emotional fault lines that shaped both her mother and her; that informed and sharpened her political imagination and taught her the importance of awareness in a fractured world. In writing the book, Roy does not seek a resolution; like the Beatles song that lent it its name, all she asks of her readers is to read the book “as you would a novel”; and of her memories, to “let it be”. In this interview, Roy speaks about love and estrangement, about inequities in power structures and what it means to finally tell the story one has spent a lifetime circling. Edited excerpts:

Mother Mary Comes to Me is a frequently heartbreaking read. Was it a difficult book to write?

You know, I do not know how to answer that question because I am always writing in my head. But I did not have any difficulty in how to write the book — as in what goes into it and what does not, which you might normally imagine would be difficult — because these are things that are seared into my memory. You cannot forget them. The challenge for me was, can I write this woman? Can I write Mrs Roy? I wanted her to be in the pages of literature, not as a hagiography, but as a woman who had no problem displaying everything that she was — good, bad, whatever. So how do you write somebody without trying to characterise them, to wrap them up neatly or to come to some resolution or allow the reader to form opinions? You cannot. That was the challenge. It was a writer’s challenge, not a daughter’s challenge.

Does that make it a writer’s remembrance or a daughter’s?

Ultimately, I think she was my daughter and I her mother. There was no possibility of ever having a conversation with her — not from the time I was three till she passed away when I had entered my 60s. So this is that conversation. Or rather, it is not a conversation, it is a reportage of a subject that does not normally require it. It was never my instinct to write a book where I try to make her or myself presentable. That would have been pointless.

You write that she liked to assume the role of Ammu from The God of Small Things (1997). How do you think she would have reacted to this book?

I doubt she would have been happy. But I honestly do not know how she would have reacted. She was so unpredictable from one day to the next, one minute to the next. So, it is not of any consequence to me what she would have felt about it because it is not written for that reason, for her approval or to please her. It is written because she deserves to be in the pages of literature, of history.

Was writing the book cathartic for you?

No, not at all. I have been dealing with all this from the time I was three years old and I am dealing with it still. Even when someone is not there, you have to deal with the person and what happened in your past. So that process will never end.

How did this inheritance of precarity prepare you for the unevenness of power dynamics in the world?

It is not just the power dynamic between her and us (Roy and her brother), but living on the edge — not at the bottom, but on the edge – of a very conservative community which made it clear to you that its reassurances and its protections are not for you. So, you end up being a child who is really, all the time, trying to figure out what is going on, what are the unwritten rules and who is what. You don’t realise it at the time but it is interesting because it is not coming from the bottom of the pile, not coming from the perspective of someone who has been oppressed socially for generations. You are looking at it and you are thinking to yourself that you do not belong anywhere in that sense. Even at home, having to handle her, because of her asthma, you could not react to anything that happened. She got my dog killed (“Because she mated with an unknown street dog. It was a kind of honour killing,” Roy writes in the book) but I could not ask where Dido (her dog) was. You just had to swallow it.

Story continues below this ad

So there was a disassociation I had even as a young child — half of me was handling whatever it was — the love or the eccentricity or the anger — and one half was literally taking notes.

You write of your mother punishing your brother for not having performed up to her expectations and your guilt at having escaped it because of your good grades.

It was not really guilt. Guilt is a corrosive thing. It was awareness. It is not that I felt it was my fault. But I was deeply aware that this is happening to me and there is that happening to somebody else at the same time. It is something that lives with me. For instance, I have written this book during the course of a genocide. I have written it while people and children are being starved and broken. I cannot be that person who does not know what is going on, not just in the country or in Gaza, but everywhere, what kind of a society we are edging towards. I never lose that sense of perspective. I am always aware that someone is being beaten in the other room.

Arundhati Roy (Penguin Random House)

Arundhati Roy (Penguin Random House)

Do you still run away from safe spaces?

Yeah. Once you’ve had a rocky and unsafe childhood, you can’t trust safety. You always think, ‘When is it going to explode, when is something going to fall on my head?’ There is always a sense of wariness. That’s one part of it. The other is that if you’re a writer, particularly the kind of writer that I am, who doesn’t know what she’ll be doing next or doesn’t have her life planned, you are always changing. And then you make that safe place dangerous. You may even jeopardise other people. This is why I keep moving away because I don’t want others to pay the price for my writing.

Part of how we locate ourselves in the world is through language. The image of the outsider-infiltrator — the ‘ghuspethiya’ — has become a recurring motif in our political language. How do you interpret this moment in our political discourse in which such language is the defining conversational currency?

Story continues below this ad

Once you start these fires, you cannot control the paths along which they will burn. For all the progress, or whatever you want to call it, that is made in weapons research, drones and AI, what we lack is a philosophy of how to be human in this world. Everything has become accusatory, language itself has become so fragmented. You have this nationalistic language and therapy language and legal language and NGO language and it is all becoming narrow and pathetic.

Do you feel that there is an acquiescence to this rhetoric? That it has affected our capacity for compassion, empathy?

Sometimes I think that a society that practises caste has already institutionalised a lack of empathy because of this hierarchical social structure and then introduced ethnic and religious violence, corporate capitalism and a complete cold-heartedness towards the poor. I don’t think there is any society like Indian society in the world today which is so cruel and uncaring of each other. One of the biggest things that we have to overcome is that kind of hierarchical thinking which closes out the possibility of your feeling something for someone who does not belong to whatever tiny group you claim you want to belong to. It’s political, it’s social, it’s economic but it’s also psychological.

What makes writers dangerous to regimes across the world? Is it their ability to find their own voice?

Historically, writers have been seen, and continue to be seen, as a potential danger to regimes. However, a majority of them are not. A majority of writers are just trying to be safe, trying to be successful and are amenable to being commodified in some way. It is when they are not that they become what they term as dangerous.

What about you?

One of the most radical ways of liberating yourself is to know that you have more than enough. The constant greed of wanting more and more is a form of slavery too, of subjugating and limiting yourself. There’s great liberation in being able to say I have enough or I have more than enough. I think it comes from having been able to make do with so little, I don’t even comprehend it (greed).

Story continues below this ad

Maharashtra has recently brought in the Maharashtra Special Public Security (MSPS) Bill purportedly to curb “urban Maoism”. How do you view this development?

It is not new. Even during Congress time, I remember them saying that the intellectuals are more dangerous. Then Amit Shah said it. The danger that comes from ideas, it is truly more dangerous than the guys with the guns eventually. But this is a sign of absolute insecurity, the absolute inability to accept that something in the system is going very wrong. So, a majority of the people of this country are just being cut loose to go drown while you have a few billionaires keeping up the GDP.

What is your relationship with the term activist now?

The reason that I react to it is because I feel it doesn’t understand activism or writing. The kind of relentlessness that activists have about whatever they’re working on, I don’t have it. I’m an explorer of things and whatever it is, whether it’s a dam or the idea of nuclear weapons or privatisation, everything informs everything else. I can’t stay in that same place and say the same things again and again, which is an important task activists carry out. The other thing that I can’t be is, when you are working with people, somewhere there has to be the ability to be like them, to live like them and all that comes with that life. I don’t have it. It would terrify me to offer myself up to be in the centre of a community because I’ve spent all my time on the edge.

Has the definition of happiness changed for you over the years?

I think if you could understand the things that make you happy, that’s a very liberating thing. For one, it’s not something that you can have permanently. It comes and goes, and you have to accept that. And if you’re a writer who derives a great amount of pleasure from design, from cinema, from so many things, then there’s a huge array of things that make you happy.

What was it like to go back and design the memorial for your mother at Pallikoodam?

It was interesting to conceptualise it because it came out of the fact that we didn’t know what to do. The church didn’t want her and she didn’t want the church. Then it came out of somewhere, the idea that it shouldn’t be a place where things are sealed; it should be a place where things are alive and you can go and talk to her. So the teachers go and read her the marks, the kids go there. She was a person who nobody could talk to. Now they can go and say whatever they want to her. A lot of people do go and speak to her there.

Story continues below this ad

Do you? Is there anything you wish you had said to her that you tell her now?

No, and that’s why this book is to her and to my brother, because we were never able to speak in the years that we had together.