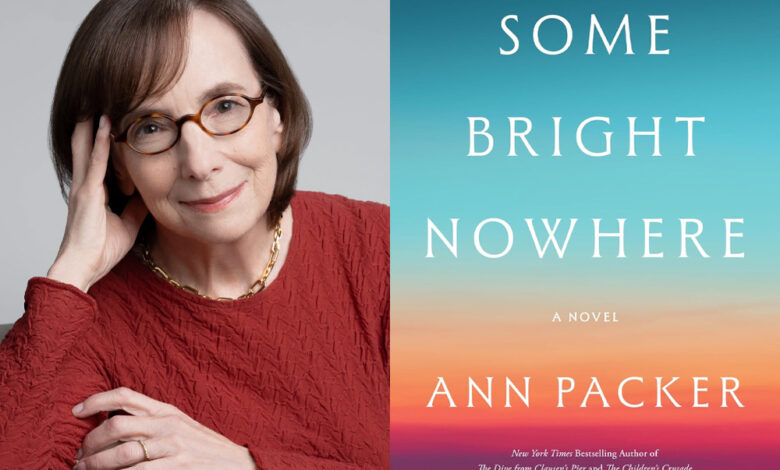

Q&A: Ann Packer, Author of ‘Some Bright Nowhere’

We chat with author Ann Packer about Some Bright Nowhere, which is an intimate and profoundly moving look at a long marriage and the ways in which a startling request can change a couple’s understanding of who they are, together and apart.

In SOME BRIGHT NOWHERE, a couple—Eliot and Claire—have been married for nearly forty years when Claire, nearing the end of a long battle with cancer, asks Eliot to move out so her two closest female friends can care for her in her final weeks. How did you first imagine that moment? What drew you to explore the dynamics of these relationships in the context of end-of-life care?

Many years ago, I heard about a situation similar to the one I portray in the novel. In the story I was told, a woman neared the end of her life, and her husband was deemed inadequate to the task of caring for her, so some women friends stepped in to be with her instead. That was all I heard; I didn’t learn anything about the people involved, what their personalities or lives or circumstances were like. Yet, despite being so thinly sketched, the story stayed with me. Or maybe it’s because it was so thinly sketched that it stayed with me: the absence of detail allowed me to imagine the specifics. I immediately understood the appeal—even the logic—of women doing the caretaking. It was easy to imagine women surrounding a dying friend with love and care, finding ways to ease her discomfort and escort her not just physically but also emotionally to her end. But the idea took for granted not just that women are caretakers but also that men are not. There’s historical truth to this notion, but it also has the power to get in the way of other possibilities. What about the husband in this scenario? Would he be relieved to be replaced, or devastated? Would he become bitter? Would he stay away? How would it affect his view of the marriage, both immediately and in the longer term?

In an expected death, every loved one will have a final communication with the person who is dying. Because you don’t know when that will be, the important things are generally said well before the actual end. But there’s still going to be a last thing you said to them and a last thing they said to you—not necessarily in that order. I thought it would be hard for both the husband and the wife to have their final words to each other witnessed or worse yet mediated by other people.

The novel’s premise came from a real-life situation you heard about nearly twenty years ago. Why do you think it stayed with you for so long, and what finally made this the right time to write it?

When it comes to writing fiction, it’s always very hard for me to answer any question beginning with “why,” because the truth is I mostly don’t know why. On the most superficial level, I can say that I wrote about this situation now rather than ten years ago because ten years ago I was working on something else. That’s a very annoying answer! But it’s also true and I think gets at something deeper, which is that the interplay between my life and my literary imagination is both constant and mysterious. I will say that I tried to work on this idea several few years ago and it didn’t work out, so that’s part of the story, too.

SOME BRIGHT NOWHERE tells Claire’s story entirely through her husband Eliot’s eyes. What drew you to stay fully in his point of view?

This ties back to the previous question of why now, and to what I said about having tried once a while ago to work on this idea. When I first began working with this scenario, I thought I would occupy each of the points of view. I began with the dying woman and moved from her to one of her friends. I imagined continuing on to the other friend and only in the final section going to the husband. But that early attempt failed to grab me. I wasn’t compelled by the characters or the voice I started with. It was some time later that I thought about why that had been and decided that the character whose point of view most interested me was the husband. At that point I started over, and the novel came together quickly after that. As for the why of it, I may have been most drawn to exploring Eliot’s perspective because it’s the most distant from my own life experience.

You have said that a central theme in your work is “the gap between what other people want us to do and what we want or need to do for ourselves.” Given that, it’s not surprising that your books are often praised for their unflinching, empathetic examinations of selfish acts. How does SOME BRIGHT NOWHERE push these ideas into new territory?

We all live in communities, which means we live among shared values. This extends from the grandest—“thou shalt not kill,” to take maybe the most obvious example—down to very minor manners and mores. If you burp you’re supposed to say excuse me; if you sneeze someone else is supposed to say bless you. At the same time, we all live inside our own minds, and it gets even more complicated when you consider that alongside our conscious beliefs and desires are unconscious beliefs and desires, often so powerful and problematic that we do everything in our power to keep ourselves from knowing about them.

For me, what’s most interesting about people is how they balance these two states of living. That’s the gap I’m referring to when I talk about this central theme in my work. Should I do what’s better for you, or should I do what’s better for me? In contemporary life there’s a high value placed on what’s often called “living your truth,” but it’s only a matter of interest because of what you have to do, who you have to cross, what rules you have to break, in order to accomplish it—essentially, what selfish acts you have to commit. So in my first novel a young woman struggled with wanting to leave her badly injured fiancé. In my second, a woman couldn’t bring herself to provide the support her oldest friend needed. In my third, a mother couldn’t bear the strictures placed on her by the mere existence of her family. And now, in Some Bright Nowhere, a man has his heart broken by what his wife wants at the end of her life. Her request can be seen as a selfish act, which makes him into the victim, I suppose. But then he has to decide what to do, whether or not to honor her wishes, which creates the possibility of a second selfish act—the act of saying no. I wanted to explore the effects of Claire’s request and Eliot’s response on the tiny community of their marriage and family.

After a lifetime of traditional gender roles, Eliot has become the cook of the family, even joining a men’s cooking group. Why did you want Eliot to have this vocation, and what role does his cooking play in the novel?

I don’t share my work with anyone until I’ve completed an entire first draft—with one exception. My husband is a writer too, and also a wonderful, very insightful reader. About 40 pages into the first draft of Some Bright Nowhere, I asked him to read what I had so far. He had one specific suggestion: he thought it would be good to give Eliot a way to interact regularly with other men. This made a lot of sense to me, and I found myself inventing a men’s cooking group for Eliot. As is generally the case, I didn’t think about why; I just wrote it. But I can see now that Eliot’s interest in and aptitude for cooking serve to represent his ability to take care of people—of Claire. Cooking is a hopeful, life-affirming, life-extending activity. Eliot has caretaking impulses; he’s not lacking in this crucial propensity. So that can’t be why she wants her friends instead of him.

Beyond that, cooking is very central to my life–it’s one of my favorite things to do–and it ended up being a lot of fun to give Eliot this interest of mine. One of the delights of spending summers in Maine is the appearance, usually in early August, of wild blueberries. (These tiny, delicious berries spoil you for eating regular blueberries.) For the short season when they appear in the grocery store, I spend a lot of time baking wild blueberry pies and muffins and scones. In fact blueberry scones play a small but key role in the way Eliot will carry his experience of Claire into a future without her.

You’ve said you wanted the book to be “like a knife” as you were writing it. What did that mean to you? How did that metaphor shape your editing and pacing decisions?

From the beginning, when I told people what I was working on I would always finish the description by saying I wanted the book to be “like a knife” and then I’d make a slicing gesture with my hand. It seems silly when I recall it, but I think I was using that simile to convey something I hadn’t spelled out to myself, which is that I wanted the book to be very short and very focused. Or, to shift the words slightly, very slim and very pointed—like a knife. To me this is a story about how little we know during the process of writing a first draft. Or how little I know—this varies a lot from writer to writer. For me, the process itself is nearly wordless—not just unanalyzed, not just unplanned, but actually unarticulated—even though the result is nothing but words. (When I start revising everything changes, and I get much more planful.) With this book I think my intention in the first draft to keep it short and very focused created a novel that is quite fast-paced despite being a very interior book. It also led me to leave out some things that both my agent and my editor encouraged me to develop, and the final book is much better for it.

The book is deeply interior, yet grounded in vivid scenes, including a key moment on the coast of Maine. What made you want to set the climactic scene there rather than in the Connecticut town where most of the rest of the book is set?

I mentioned having started an earlier version of the novel with the idea of moving among points of view: first that of the dying woman, then those of her friends, and finally that of the husband. For that last part, I had one idea pressing in on my imagination: the husband surprising the wife and her friends at a house on the coast of Maine. I spend summers in the small town of Brooklin, Maine, and I was very much thinking of the cove where we have our house. I pictured this husband outside a house—not ours exactly but geographically near ours—while his wife and her friends were inside. I had a very dark tone in mind for his entry into the women’s world. And I had a sense that later, with the darkness dissipated, he would carry his wife outside to look at the water.

All of this made the journey with me, from the first attempt to write this story all the way to Some Bright Nowhere. The why is hard to pinpoint, but as I wrote toward the climactic moment, the scene and the idea of Maine were never far from my mind, and I wove references to Maine and to what it meant to the couple all the way through the book, to set the stage. Intellectually I can see that the characters needed to be in a different place for this moment to unfold, but my honest answer is that I’d begun to imagine it even before I started the final version of the novel, and I had to see it through.

SOME BRIGHT NOWHERE is a book about many things – the choices we’re confronted with at the end of life, marriage and gender roles, family and friendship. What conversations do you hope this book sparks with readers?

I’m delighted and honored that my work sparks conversations of any kind, and I wouldn’t want to point readers to any particular topic of conversation over any other. The book, once it’s in a reader’s hands, belongs to that reader and is theirs to engage with according to who they are. That said, I think a lot about the subject of impending death and how that can be a tough thing for people to grapple with. I’d be pleased if the experience of reading the book prompted conversations about the end of life and helped open and normalize engagement with what is after all the only truly inevitable thing we face.

Will you be picking up Some Bright Nowhere? Tell us in the comments below!

Source link