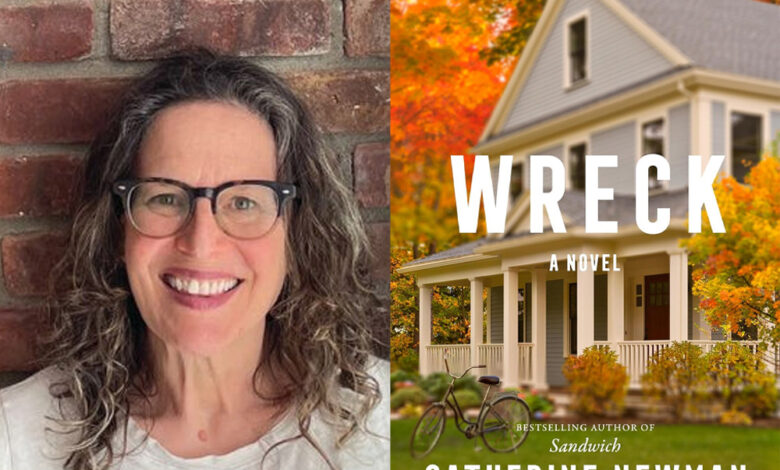

Q&A: Catherine Newman, Author of ‘Wreck’

We chat with author Catherine Newman about Wreck, which is full of laughter and heart, about marriage, family, and what happens when life doesn’t go as planned.

Hi, Catherine! The title WRECK has emotional, literal, and metaphorical resonance. Without giving too much away, can you share a bit about what it signifies?

On the one hand, I think of wreck in the most colloquial sense: “Ugh, I haven’t slept in days, I’m a total wreck!” That’s Rocky—both that she barely sleeps, and that she’s usually kind of a wreck. But also, in this book, there’s a quite literal wreck: a young person with whom Rocky’s kids went to high school is killed in a collision between his car and a train, and Rocky becomes obsessed with this accident and the mysteries surrounding it. Also, in a parallel story, she is being diagnosed with a mysterious illness that is threatening to wreck their lives. If only there were a town in Massachusetts named Wreck, it would really be the perfect title! Ha ha ha. (Excuse my very niche Sandwich joke.)

You write often about the body—its fragility, its failures, its surprising resilience. What draws you to that subject?

We are always embodied, like it or not, even if the part we mostly identify with is our thoughts. And even if our body is failing us. We are not a brain in a jar, for better or worse. It’s one of the big themes of Sandwich—the reproductive and, then, menopausal body—because I really wanted to write about how your body comes everywhere with you, even if it’s not really what you remember about a given time. So, yes, it’s the sand and sunsets and the candy-striped pastel joy of a vacation, but also you had your period or a stomach bug or you were hungry or pregnant, nursing or miscarrying or you had to pee. Wreck brings Rocky’s attention to her body right into the present tense because she’s in the baffling process of being diagnosed with a mysterious illness, even though she feels pretty good. So she becomes obsessed with the secrets her body might be keeping from her, and, in lieu of diagnostic clarity, she spends too much time in her medical portal and she keeps turning to the internet for answers. (This, you won’t be surprised to hear, doesn’t usually go well.) I’m always drawn to books about failing bodies, and three current favorites are: Samantha Irby’s Quietly Hostile, because there is nobody more hilarious and generous than her; Garth Greenwell’s Small Rain, which is a poetic and gorgeous story about a mysterious illness; and Meghan O’Rourke’s The Invisible Kingdom, which is part memoir and part journalistic exploration of autoimmune illness, a hybrid genre I love.

The novel unfolds as the seasons change—from fall into winter. Does this timeline have any significance to your characters and their evolution in the book?

Each of my three novels has taken place in a very specific season. We All Want Impossible Things takes place almost entirely in February; it was based very closely on my real-life experience of losing my best friend, who finished dying during an especially long and brutal February, and all the snow and cold and slush and darkness felt completely integral to the story, as did the cozily illuminated interiors and the fact that the book ends with the beginning of March, which always signifies a hopeful time to me. Sandwich is a beach vacation and so it’s pure summer, of course. And then this book, Wreck, tracks all these transitions—transitions in Rocky’s health, in her emotional well-being, in her household—and that is always going to be fall for me. I love fall in New England so much, and it was a great joy for me to walk around with my eyes open to all of the details of it I might want to write about. Also, I wanted part of the climax of the book to unfold over Thanksgiving, both because that’s a classic moment of family drama and because gratitude is such a huge theme in the book.

Rocky is in the “sandwich generation,” caring for both children and aging parents. In WRECK, both her adult daughter and father have moved in under the same roof. Why is this phase of life so ripe for storytelling?

Not to sound overly unimaginative, but I think I’m drawn to this phase of life because it’s the phase of life I’m currently living through. And yet I do think it’s a uniquely resonant one. Young adult kids and aging parents can both need a fair amount of caretaking, but both populations can also profoundly resent it so, in addition to the caretaking itself, there’s this kind of smoke and mirrors thing you have to do the whole time so as not to jeopardize anybody’s dignity. We’re all so fragile, aren’t we? People want to be loved and cared for, but also to be reassured that they’re vital and necessary. Lucky for Rocky, the very people she is called on to tend are also the people who have the most wisdom and solace to offer her. Unsurprisingly, this is true for me too.

You’ve written memoirs, children’s books, and now several novels. What does fiction allow you to do that memoir doesn’t—or vice versa?

I think about this all the time—the way I couldn’t really write the truth until I switched to fiction. Which is counterintuitive in every way, of course. Memoir seems like it should be the genre that best expresses true experience. I mean, you’re basically saying: This is exactly what happened. And yet! Memoir turns out to be so constraining—both because you don’t always remember everything and because other people’s lives and revelations are at stake. You can’t just blurt out other people’s stories, so you’re stuck frantically gesturing at them, which is impossible. I love being able to make something up to express the bedrock truths of my life as I’ve lived it—my relationships, my embodied experiences, my emotional landscape, the deep and complicated and also shockingly simple love I have for my children, husband, and parents. But I also have to admit that almost all of the best lines are lifted directly from real-life dialogue because I live with the funniest, most generous people in the world.

Will you be picking up Wreck? Tell us in the comments below!

Source link