Revisiting Colonial Indian Short Fiction: A Timeless Reflection on Caste, Patriarchy, and Gender Norms

What can translations of Indian short fiction originally published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries possibly tell us about our lives today? Indeed, why seek out such stories at all in this day and age? Mini Krishnan, who has edited such a series of anthologies of “classic stories” translated from the Kannada, Malayalam, and Odia for HarperCollins India, makes a persuasive case for them in her introduction: “Our translated literature should be seen for what it is and can be: not just a part of history, but a bank, a treasure house of our own pasts because memory is the cement of our identity.”

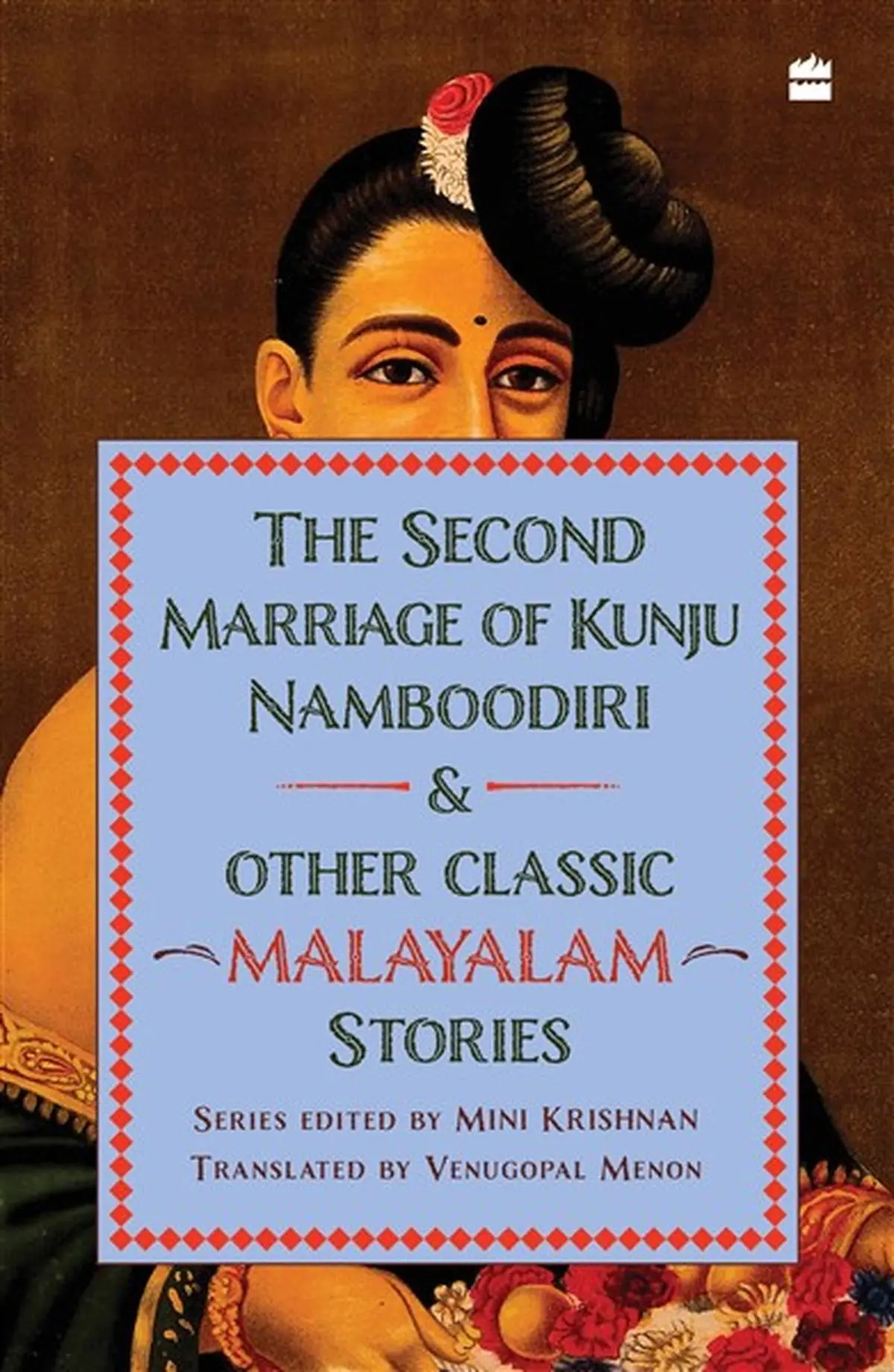

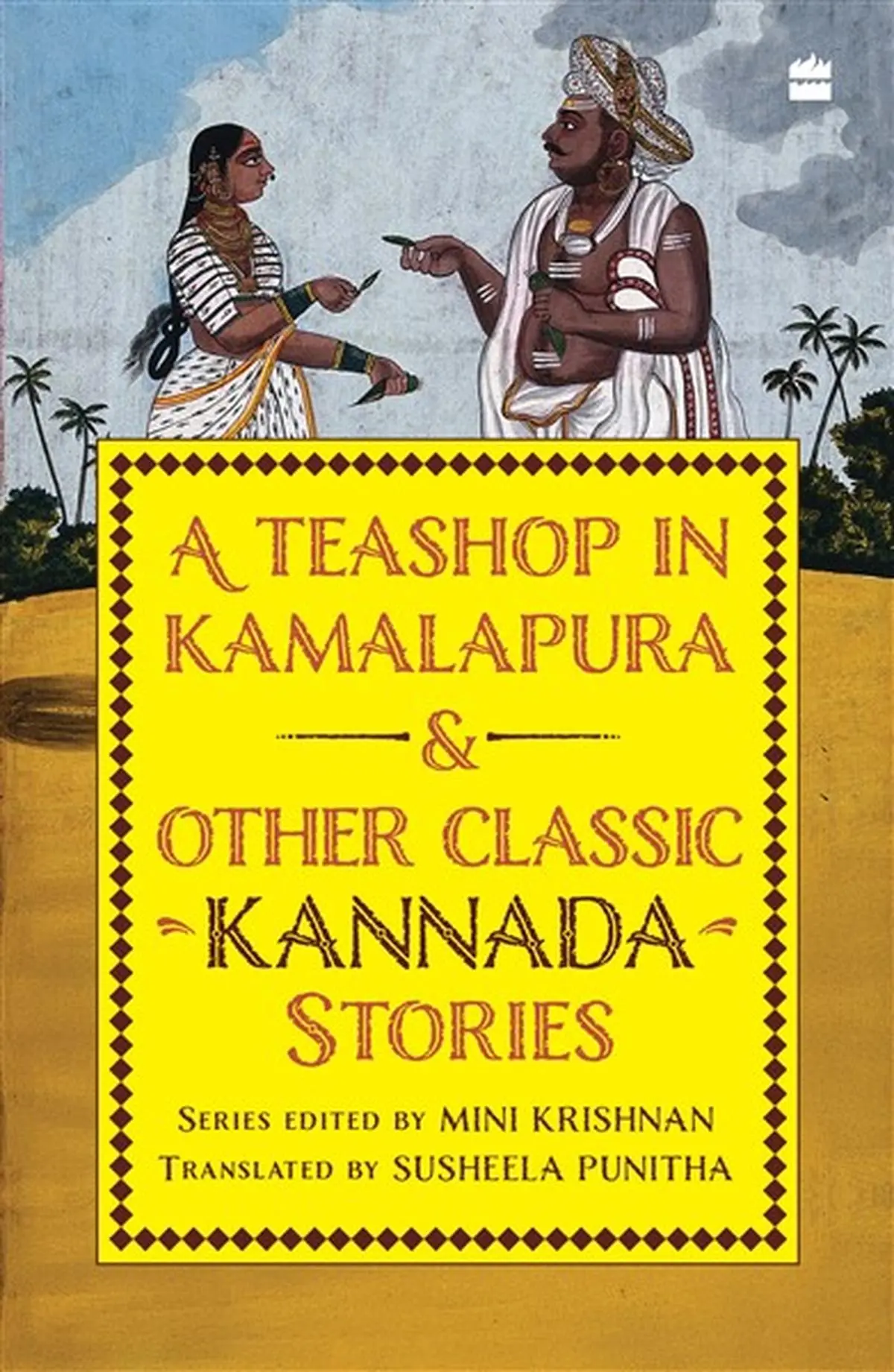

Set mostly in colonial India on the cusp of modernity, and with themes ranging from women’s education and caste politics to fantasy and social satire, the stories across the three anthologies—A Teashop in Kamalapura and Other Classic Kannada Stories translated by Susheela Punitha; The Second Marriage of Kunju Namboodiri and Other Classic Malayalam Stories translated by Venugopal Menon; and Maguni’s Bullock Cart and Other Classic Odia Stories translated by Leelawati Mohapatra, K.K. Mohapatra, and Paul St-Pierre—resonate uncannily with our times. There are stories of male fragility, the sanctification of marriage, and the politics of beauty that unsettled this reader with their unvarnished patriarchy and misogyny. Sadly, they remain as relevant today as they were a century ago.

Also Read | What makes a classic?

In “Two Ways of Living” (originally published circa 1955-65), a Kannada story by Triveni, a horse quips: “How artificial can these creatures be? No one can be so inhuman.” That could well be an observation about the characters of abusive, egotistical men that appear in several stories across these anthologies. Patriarchy, in these stories, revels in a multitude of forms: in the subjugation of women and their consequent abuse but also their sanctification and paradoxically, but perhaps not surprisingly, their objectification.

One of the most striking stories in the Odia anthology, Fakir Mohan Senapati’s “Rebati” (1898), tells the story of a spirited young girl’s love for learning in the time of cholera. It ends tragically with her death but also the deaths of everyone who supports her: her father, Shyambandhu Mohanty, her teacher Basudev, and her mother whom the author manages to leave nameless. It is almost as if they all pay the price for choosing to support the idea of women’s education.

The only survivor is Rebati’s grandmother who curses and berates her for wanting to study in the first place—a reminder that, more often than not, patriarchy enlists women among its enforcers.

The Malayalam anthology brings together stark contrasts. If M. Saraswatibhai’s “Witless Women” (1911), considered one of the earliest feminist stories in Malayalam, turns a tale of male superiority into a delightful satire, Thachetta Devaki Nethyaramma’s “An Ideal Wife” (1919) upholds unquestioning submission to an abusive husband as virtue.

“There are stories of male fragility, the sanctification of marriage, and the politics of beauty that unsettled this reader with their unvarnished patriarchy and misogyny. Sadly, they remain as relevant today as they were a century ago.”

In “Witless Women”, Govindan Nair, the “editor of a paper and a contributor to several journals” declares: “The minute a lady begins to work for money, she loses her dignity and her femininity. Such a lady needn’t remain my spouse.” What Nair does not know is that his wife Kalyaniamma (one of the few female characters in these anthologies who are referred to by name) has been writing under the male pseudonym of Balakrishnan Nair and steadily earning acclaim. “Witless Women”, which makes a clear case for women’s financial independence, ends with Nair promising Kalyaniamma: “We will spend the rest of our lives together, contributing to the world of literature.”

In “An Ideal Wife”, even though Janakiamma gets an opportunity to escape the clutches of her abusive husband, Raghava Kaimal, and go away with her former lover, Balakrishna Menon, she chooses not to. When she finds Kaimal bleeding profusely, she decides: “Serving my husband is my solemn duty. I must not desert him in this state.” This thread of marital sanctity also runs through other stories across the anthologies.

Some of them had this reader wondering at the ways in which colonialism has refracted ideals of beauty for men and women alike. More than one story extols a pale complexion as a sign of beauty, which in turn is seen as synonymous with morality. While “fair skin”, “moderate build”, and delicate features recur as signs of virtue, darkness is all too often coded as evil.

In C.P. Achutha Menon’s “My First Fee” (1894), a Malayalam story of a dispute and its settlement, Shankarankutty Menon states: “My readers would want to know more about the figure of the woman who stole my heart at first sight. Feature to feature, she did not possess great beauty. Her complexion was not startlingly attractive, except that it was more fair than dark.” The conflation of desire, beauty, and complexion here is unmistakable.

On the other hand, in the Kannada story “The Girl I killed” (1931) by Ajampura Sitaram, the protagonist describes Chennamma, who offers sex to her guests to satiate her parent’s vow to God, as “dusky” and “quite attractive”.

The protagonist of “New Tongue” (1933), a Kannada short story by Srinivasa Kulakarni, professes: “I don’t speak roughly to my wife. I treat her like a flower, placing her on my head. What a slender body, tender mind, pleasing face and such wide innocent eyes that can be forgiven at any fault!”

In this story—written from the point of view of a husband who demands that his wife call him by his name, which, ironically, is not revealed—the women ends up getting assaulted by the husband anyway, in spite of her slender tenderness.

It follows that men, too, are bound by this colour code: a fair-skinned man is gentlemanly, while a dark-skinned one is morally suspect. The Malayalam story “Just a Glimpse” (1909) by Moorkoth Kumaran has this description: “He was very dark-skinned; his nature was darker.” In another story, “I Felt Ashamed” (1905) by Kalyanikutty, the narrator says: “He must have been around twenty-two. Very fair skinned; not more than five feet tall. He was of proportionate build. He had a pleasant expression. Overall, a gentleman.”

In the Odia story “The Witch” (1935) by Biswanath Rath, the childless widow Pitei whom the village brands as a witch is “dark, pock-marked, with protruding teeth”, as if her very appearance is justification for persecution.

Within the precincts of patriarchy, the lack of conventional beauty in women is occasionally compensated for by their diligence. In the Kannada story “Vani’s Confusion” (1939) by Kodagina Gowramma—in which Ratan takes to his neighbour Indu because of her “dutiful” nature—the narrator says: “[T]hough the real Indu did not match the beauty of his dreams, her diligence compensated a hundredfold.” The colonial context of beauty and patriarchy cannot be disputed but the question persists: has the postcolonial world resurrected itself from this prejudice?

Some stories intersect with politics more directly. Yarmunja Ramachandra’s “The Idol That Chennappa Destroyed” (1953) draws on the anti-caste, anti-idolatry protests of E.V. Ramasamy Periyar’s Dravidar Kazhagam movement, while others, like Kadengodlu Shankarabhatta’s “My Alarm Clock” (1934), sanctify the patriarchal order through dialogues such as Krishnayya’s, who asks the rhetorical questi: “Isn’t the husband the wife’s God, Venkamma?”

Also Read | San Rechal and the black mirror India refuses to face

Whilst reading these stories, I was often reminded of Mulk Raj Anand’s classic circadian novel Untouchable (1935), which speaks about caste violence and social oppression in powerful ways through its protagonist Bakha. Although a few stories in these anthologies do touch upon caste violence, the feudal system, and oppression, they do not necessarily centre their stories around Dalit protagonists.

Do these anthologies qualify as “classics”? As Krishnan reminds us, they are indeed cultural “memory cement”. Yet their relevance rests less on timelessness and more on what they force us to confront. They remind us that caste and patriarchy continue to thrive in literature and cinema even today.

Across these variegated stories, the boundaries of patriarchy prove elastic: when beauty fails, diligence is demanded; when independence surfaces, obedience is enforced. They lead us to think about the many ways in which we inherit, critique, and transform the prejudices embedded in literature.

In the end, the question is not whether these stories are classics, but whether we can read them as provocations—to measure how far we have travelled and how far we still have to go.

Ilavenil I.T. was an intern with Frontline.

Source link