The boxing ring and the nail salon are not that different for author Souvankham Thammavongsa

If you’ve ever been to a nail salon, you’ve probably been told to pick a colour.

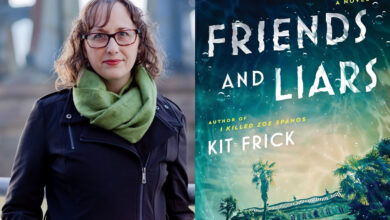

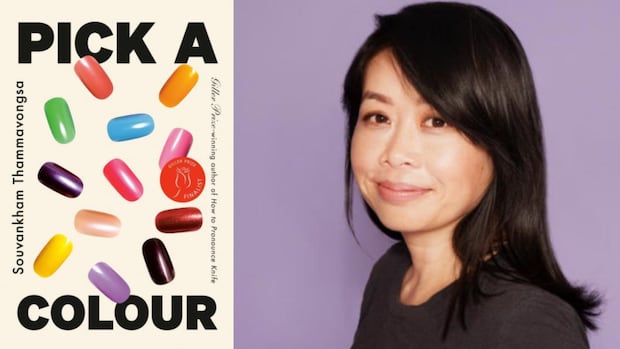

Pick A Colour is also the title of Souvankham Thammavongsa’s debut novel, which takes place in a nail salon over the course of a single work day.

It’s about Ning, the owner of the salon, who was a boxer before she became a nail technician, melding two seemingly different worlds — that of beauty and aesthetics with the hardened, oftentimes bloody, boxing ring.

“I think that’s what’s really interesting for a writer to work with, to create a universe where these two different worlds fit together and to make it feel seamless,” said Thammavongsa on an episode of Bookends with Mattea Roach.

Toronto-based Thammavongsa won the Giller Prize in 2020 for her story collection How to Pronounce Knife. She draws from one of those stories in her new novel, Pick A Colour, which is shortlisted for the 2025 Giller Prize.

Thammavongsa joined Roach on Bookends to talk about her fondness for nail salons and the kinship people find there.

Mattea Roach: What is important about that missing finger as a character element for Ning?

Souvankham Thammavongsa: I’m a writer of absence, so I love the idea of removing something and then never bringing it back for the reader. But to make that removal such a presence for a reader throughout the novel, you never know why or what exactly happened to that finger. You just know that it’s missing and it becomes a character in itself right to the last page.

Ning is smart and quite cynical but she has a sense of humour. She’s almost 42. She’s single. She doesn’t have any children. She calls herself a family of one. What did you want to explore through Ning as a character?

A lot of themes, like the idea of loneliness, what people call love, that it doesn’t actually have to be attached to a person. It could be your work, the place that you show up to every single day, the way that she’s so devoted to her work and to the women around her, her coworkers, her clients.

She is alone, but she’s not lonely exactly. She’s deeply fulfilled. And I think that may come across to others as what they would call strange, but I would not call it that.

Why do you think people might find it strange? Because it is unusual for a person to be so content?

Well, anytime we go to a family gathering, whether it’s a barbecue or holiday, the first question if you arrive there alone is: when are you going to find someone? When are you going to be partnered up, like it’s a disease or like there is something wrong in wanting to be alone.

This book is about the celebration and joy and happiness of choosing for yourself and being alone and content as a woman in her mid-40s.

Are there any misunderstandings, assumptions that people might have about nail salons that you wanted to subvert in this novel?

Yes, the way that nail salon workers have been written about, they’ve been seen as in a pitiful frame, that it’s a lowly job, someone without power, forced to work. But I have cousins and friends who work in nail salons and they make loads of money.

If you’ve ever had a conversation with anyone who works in a salon, they’ve got really hilarious stories and I wanted to show, right from the start, that it looks like they’re not in charge, but they are.

They know everything about the person who’s sitting in my chair just by looking at their toes or their hands.

You’ve mentioned that when you go into a nail salon anywhere in the world, it feels like you can go in and find friendship or kinship. What is that like for you? How does that happen?

Wherever I am, I go in there, and I make an appointment and I’m told to pick a colour. I can bring up anything I want to talk about, whether it’s a great restaurant in that town, even where I might be able to find a job.

Or I can tell a secret that I’m carrying around with me that I can’t tell a friend or anyone I know, and I can leave it there.

Why do you think that people go to these spaces, nail salons, hair salons, and are able to deposit these secrets that they maybe can’t even tell people that are very close to them?

We live in a world where we don’t get that close to people physically. We don’t have permission to get that close to people. And when we’re in that kind of setting when someone touches our hair, our hands or our toes, we feel some sort of closeness that maybe we’re not able to create with language itself.

But then the physical proximity to another person in that setting requires or opens up something where that kind of language is permissible.

Bookends with Mattea Roach25:34Can your nail tech throw a mean right hook?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. It was produced by Katy Swailes and edited by Sarah Cooper.

Source link