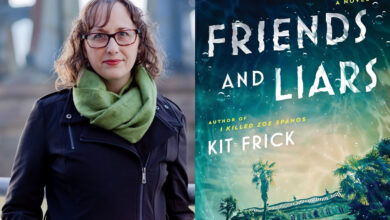

Tim Weed found key to his quest story sailing past Tierra del Fuego

Tim Weed is the author of “The Afterlife Project” and two previous books of fiction. He is the recipient of the Tobias Wolff Award for Fiction, the Montana Prize, the Fish International Short Story Award, and multiple Writer’s Digest Fiction Awards. He serves on the core faculty of the Newport MFA in Creative Writing and is the co-founder of the Cuba Writers Program. A former expert for National Geographic Expeditions, Tim spent the first part of his career directing international educational programs in Spain, Portugal, Australia, and Iceland. Tim grew up in Denver and Littleton, Colorado.

SunLit: Tell us this book’s backstory – what’s it about and what inspired you to write it?

Tim Weed: It’s a quest story, essentially, in which a team of scientists working in the aftermath of a disaster that had brought humanity to the brink of extinction sends a lone test subject 10,000 years into the future to discover whether anyone might have survived. This test subject is microbiologist Nicholas Hindman, who finds himself stranded in a lush wilderness that survived the catastrophic effects of climate change.

UNDERWRITTEN BY

Each week, The Colorado Sun and Colorado Humanities & Center For The Book feature an excerpt from a Colorado book and an interview with the author. Explore the SunLit archives at coloradosun.com/sunlit.

Despite his crushing fear that he’s the last man on Earth, Nick explores this new-yet-familiar world for evidence of civilization. Meanwhile, back in 2068, four surviving members of the team embark on a perilous transatlantic journey to find a second viable test subject, risking heatwaves, oceanic mega-storms, murderous gangs, deranged cult leaders, and a volcanic eruption, among other perils. There’s also a kind of impossible love story conducted across the chasm of 10,000 years.

In terms of inspiration, I can actually trace it back to a single moment. I was working as a traveling lecturer for National Geographic Expeditions, and I found myself on a small-ship cruise through Tierra del Fuego and around Cape Horn. There were some interesting fellow passengers aboard, including an astrophysicist who was the director of Hawaii’s Mauna Loa observatory and a young paleoclimatologist from Princeton.

At the time, I was hoping to embark on a new novel project, one that would incorporate bigger topics like the climate crisis, the biodiversity crisis, and the potentially clouded future of the human species. My interest in this subject matter was partly aesthetic—I thought it would be a fun challenge to take on these big questions in the framework of a novel—and partly for the sake of my own sanity. As I’m sure is the case for many of us these days, I’d been brooding and worrying about the future.

So I knew more or less what I wanted the novel to be about, but I hadn’t really figured out the story itself or how to write it. Then suddenly, in the midst of a casual dinner-table conversation, with the vast unpopulated wilderness of Tierra del Fuego sliding by outside the ship’s picture windows, an idea came to me.

I asked the astrophysicist about the plausibility of one-way time travel into the deep future. He took out a pen and started jotting down equations on a napkin using concepts from general relativity and quantum physics. By the end of the trip, he was able to come up with a theoretically plausible mechanism for one-way time-travel ten millennia into the future.

“The Afterlife Project”

Where to find it:

SunLit present new excerpts from some of the best Colorado authors that not only spin engaging narratives but also illuminate who we are as a community. Read more.

I had permission to run. It would take a lot of research, and numerous full drafts, but the novel that would eventually become “The Afterlife Project” was on its way.

SunLit: Place the excerpt you selected in context. How does it fit into the book as a whole and why did you select it?

Weed: There’s a chapter late in the book that actually takes place amid the ancient ruins of Denver and along the Front Range, and I thought of excerpting that given the Sun’s Colorado audience. But because of where it is in the narrative it contains some important spoilers, and would require additional context to fully understand.

The early chapter that appears here is basically setting the stage for the 2068 timeline, in which the remaining scientists on the team sail across the Atlantic Ocean in a solar-powered yacht to a small volcanic island north of Sicily in search of one or more additional test subjects.

SunLit: What influences and/or experiences informed the project before you sat down to write?

Weed: I was inspired by novels such as Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road,” Peter Heller’s “The Dog Stars,” Emily St. John Mandel’s “Station Eleven,” David Mitchell’s “Cloud Atlas,” Richard Powers’ “The Overstory,” and Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings”—each of which offered specific lessons about approach and technique that I applied to “The Afterlife Project.”

I was also influenced by a particular place that’s important to me: a little hilltop outlook on a local trail system I often hike or run, with a sweeping view of forested valleys, foothills, and distant mountains. I returned to this particular place frequently while I was writing the book to reexperience the feeling of what it would be like to be a stranded time-traveler scanning an uninhabited wilderness for signs of his fellow humans.

“The Afterlife Project” was also directly inspired by a number of nonfiction books about deep time, the history of the planet, the five mass extinctions life on Earth has already undergone, and speculations about how the future would unfold were humanity suddenly to disappear. These are actually some extremely interesting books if you have any interest in these topics. Here’s a link to that book list.

SunLit: What did the process of writing this book add to your knowledge and understanding of your craft and/or the subject matter?

Weed: Don’t write to the market. It’s really a much better idea to write what’s truly organic to your heart and your imagination; to write the book that you would truly want to read, but that doesn’t yet exist. I mean it’s okay to think about the market before you start, and you’ll need to think about it when it comes time to pitch and sell it. But I really advise against focusing on the market while you’re writing.

I wrote a weird, dark, unconventional, objectively far-fetched novel. I didn’t set out to make it that way, it just happened. I couldn’t not write it; it turned out to be one of those books that felt like it was being dictated from on high. When a story feels like that—when it starts to tell itself like this one did—you just have to ride the wave and hope for the best. As Mexican novelist and filmmaker Guillermo Arriaga put it to me a few years ago at a conference, you’re writing for what is in your own particular “species.” You have to trust that there are other members of that species out there, and that they will eventually find your book.

Learn about the market, of course; study it and understand the genres you’re working in. But if you try to write purely for the market, the muse is very likely to turn her back.

SunLit: What were the biggest challenges you faced in writing this book?

Weed: You might call it “psychological management.” Writing a novel is a lot of work. It takes months and even years of steady, daily, incremental creative labor, and that creative labor is hard: mentally, emotionally, energetically.

I didn’t have a literary agent for the entire time I was drafting “The Afterlife Project.” Though I’d already published two books of fiction, what I was doing was completely speculative in both senses of the word, and it was also a pretty far out premise, not like anything else I’d ever written, and not directly comparable to any existing novel that I knew of. It was a big leap in the dark, in other words, and the hardest challenge was just holding on to my sanity and sense of self-worth; finding ways not to despair as I used up all my writing hours over all that time without having any idea whether or not it was ever going to get published.

But it paid off! And that’s a message I would convey to others out there who are struggling with the long-term creative labor that goes into writing any novel. Each novel you write is a profound and worthwhile education. If your work-in-progress doesn’t end up making it out into the light, the next one will, or the one after that. You just have to keep going.

SunLit: What do you want readers to take from this book?

Weed: First and foremost, I want them to be entertained. I’m a big believer in the intrinsic value of escapist fiction, and I wanted the novel to be suspenseful and alive on the page in a way that made it difficult for a reader to put down—and in way that when they finish it, they will feel a sense of catharsis, or satisfaction, and will be glad to have read it.

I suppose part of my goal in writing “The Afterlife Project” was also to give readers an emotional experience that makes it clear what we as a species currently have, and what we stand to lose.

If there’s one piece of wisdom I would wish for people to take away, it comes from the geologist Marcia Bjornerud, in her wonderful nonfiction book “Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World.” That is, it’s not the end of nature we’re contemplating; rather, it’s the end of the illusion that we’re not part of nature. That we’re not fully embedded in the ebb and flow, the stew and ferment of life on this immensely rich and complex 4.5 billion year-old planet.

SunLit: Tell us about your Colorado roots. Do you have any book events coming up in the state?

Weed: My ancestors on my mother’s side came to Colorado in the early 20th century, living for a time as sharecroppers in the eastern part of the state before moving to Denver. My grandfather became a general practitioner and worked at St. Luke’s hospital in Englewood; he was also the company doctor for the Public Service Company of Colorado (PSCo) for many years, where I was lucky enough to hold a summer job during college.

My paternal grandparents moved from Chicago to the foothills above Golden in the 1940s, looking for a new start in the wake of the financial ruin they’d experienced in the Great Depression, and ran a little country store in Genesee Park, near their home at the Mount Vernon Country Club. My parents both grew up here, and I myself was raised partly in Denver and Littleton. My mom and stepfather still reside in San Juan County, and although for complex reasons I currently reside in Vermont, I’m a Colorado writer at heart, by both heritage and upbringing.

In terms of book events, I’ll be at The Tattered Cover (Aspen Grove) on July 11, the Mesa Verde Literary Festival on July 12, and Townie Books in Crested Butte on July 15. Would love to meet any Colorado Sun readers at one of these events!

SunLit: Tell us about your next project.

Weed: My next novel, coming out in 2026 (also from Podium Entertainment), is “The Gatepost,” a contemporary portal fantasy blending science, ancient cosmology, psilocybin hallucinations, and the vast expanse of geological history. Recent comps might include Susanna Clarke’s “Piranesi,” another portal fantasy with a character stuck in an uncanny and possibly hallucinatory parallel world, and Eleanor Catton’s “Birnham Wood,” a literary thriller in a rural setting with the hidden machinations of a powerful tech entrepreneur looming in the background.

A few more quick items:

Currently on your nightstand for recreational reading: “Burn,” by Peter Heller; “No Lie Lasts Forever,” by Mark Stevens; and “The Dark Tower and Other Stories,” by C.S. Lewis.

First book you remember really making an impression on you as a kid: JRR Tolkien’s “The Hobbit” (followed quickly by “The Lord of the Rings”).

Best writing advice you’ve ever received: Get writing! Don’t hoard your ideas, or save them for some hypothetical future use. When you get an idea for a story or a novel, write it now. Don’t worry, you’re not squandering your inspiration or your best ideas; new ideas and new inspiration will backfill behind it. Also, if you can, try to write at least a little bit every day. Incrementalism conquers the world.

Favorite fictional literary character: Unfair question! So I’ll cheat by naming multiples: In terms of older novels, maybe Tolkien’s Gandalf or Robert Graves’ Claudius, Graham Greene’s Wormold, or Larry McMurtry’s Augustus McCrae. In more recent novels, Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell, Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, and Kasuo Ishiguro’s “artificial friend,” Klara. All of these literary characters have stuck with me like old friends.

Literary guilty pleasure (title or genre): The early spy novels of Ken Follett and John le Carré. Though come to think of it I don’t feel at all guilty for appreciating the work of these master storytellers.

Digital, print or audio – favorite medium to consume literature: Print is still tops in my book, though I’ve also been appreciating audiobooks quite a lot lately.

One book you’ve read multiple times: John G. Neihardt’s “Black Elk Speaks.”

Other than writing utensils, one thing you must have within reach when you write: A heavy, smooth, rock that fits nicely in my hand. My “worry stone.”

Best antidote for writer’s block: Keep the muse on your side by showing up every day and holding yourself to getting some words down on the page. One secret that I learned from an oil painter is that it doesn’t have to be good, and it doesn’t have to be a lot. Sometimes a single brush stroke (or for a writer, a single sentence) is enough, as long as you “touch” the work every day.

Most valuable beta reader: I’m part of a writing group and have a few good friends who are willing to read and whose opinions I trust. Currently, though, I’d have to say that my most important beta reader is my literary agent, Deborah Schneider. I’m so fortunate that she’s a good reader who understands storytelling and the market and is also extremely honest.

Source link