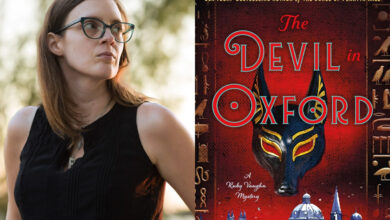

Writer Hernan Diaz heads to Tulsa | City Desk

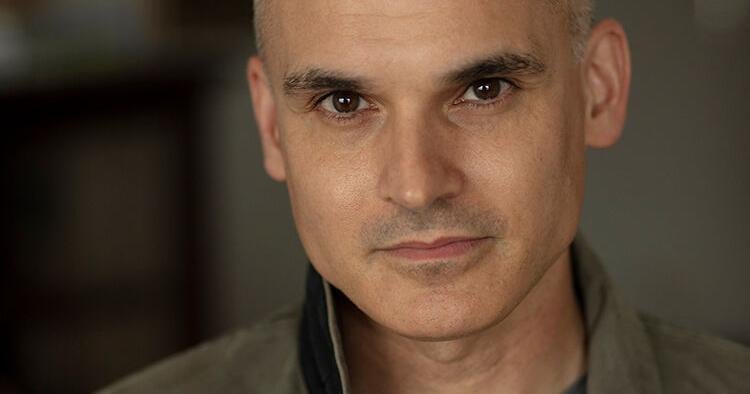

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Hernan Diaz is coming to Tulsa Dec. 4-5 to accept the 2025 Peggy V. Helmerich Distinguished Author Award given by the Tulsa Library Trust and Tulsa City-County Library.

With three books published in 37 languages, the Argentine American writer is a recipient of the John Updike Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Whiting Award and a fellowship from the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers.

His first novel “In the Distance” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award, among other distinctions.

“Trust,” his second novel, also garnered many prestigious distinguishments including the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2023; it was listed as a best book of the year by over 30 publications and was named one of Barack Obama’s Favorite Books of 2022, as well as one of the New York Times’ 100 Best Books of the 21st century. “Trust” is also currently being developed as a limited series for HBO starring Kate Winslet.

Diaz spoke with us ahead of his visit to Tulsa from his home in Brooklyn.

What was your origin story of becoming a writer? Was there something that prompted you, or did it develop in you organically?

There was nothing else in the cards for me, I never wanted to be anything else other than a writer. I started to write as soon as I learned how to write — short stories, awful poems — and then I became an academic and a critic. So I knew from very early on.

I became an academic because I was uncertain that I would be able to make a living out of writing … I was hoping to become a full-time writer since I was a child and it only happened last year when I quit academia.

Who were the writers that inspired you growing up?

Oh, so many of them. I grew up in Stockholm, and I loved reading comic books. That was a big, big influence for me. And I think my writing is still very informed by that visual component and how you drive a story forward without necessarily, overtly narrative elements, but just through atmosphere. I’m thinking of the wordless panels in comic books, you know, that can do so much narrative work.

But again, there’s just no text … of course a novel is always text, but I’m interested in those moments that kind of push you to further a narrative situation through unexpected means. So comic books were very important.

Then two Argentine writers were also hugely important to me — (Julio) Cortázar … his short stories were very important for me, and (Jorge Luis) Borges, arguably one of the greatest writers of the 20th century if we care to rank writers, which is a silly endeavor to begin with

And then I think Franz Kafka, too, was a huge, huge influence of my teenage-dom. And Edgar Allan Poe … They’re very unstable writers in the most productive sense of the word, I mean how boring is stability in art, right? They really do make you reconsider the very notion of experience — how we interact with what we have agreed to call reality, who we are as holders of that experience, and how we may convey that experience to others. That’s why Poe, for example, is kind of the godfather of unreliable narrators.

And I think what’s at the core there is experience, and reality, and how we may hope to communicate this to others, and what distortions come into play in that communication. These are things that interest me always, in everything that I write.

Your first published work of fiction “In the Distance” came out in 2017. Can you describe your writing journey up to that point? What challenges did you face?

During all those years I was writing and being universally rejected by the publishing industry — in different countries, I may add — but mostly in the United States … I went through a big heartbreak being unable to publish the previous novel before “In the Distance” that I still believe in as a book, but it shall remain unpublished.

I didn’t have an agent, I didn’t have a publisher, obviously, I didn’t have any connections … So “In the Distance” I sent cold up to a slush pile of a small independent press that accepted submissions once a year, one day. They took it and they published it, but they could just as easily not have taken it or published it, and I would still be writing in total obscurity, but I would still be writing.

“In the Distance” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

What is the driving force that keeps you in your chair, writing through all the challenges?

I love the craft. This is not a sound business model, becoming a fiction writer (laughs). I just love language. I love books. I love beautiful sentences, reading them, hopefully producing them. And if I didn’t love it, I wouldn’t do it.

Although I love it, it’s also true that some days are very difficult and very frustrating and just plagued with doubt and thinking you suck, and thinking that the book sucks. And sometimes that’s OK if you’re on month number two of a project.

But if you’re on year number three, and you think that the book sucks, then that’s really not a good feeling to have. So it is scary … I take (writing) extremely, extremely seriously. There is no cynicism. There is no outside of it. Even if it fails, or if I feel that it’s failing — and I don’t mean commercially, I mean on the page — it’s really a matter of life or death. For me, it feels the stakes are very high. So sometimes that is not an awesome feeling … That is a possibility of a writing day.

(But) other possibilities are just joyful, and I’m lost in it, and I feel that I’m taking dictation from someplace else, which is the best feeling. You’re kind of surfing language, and it’s great, and ideas keep coming in, and you’re excited about where the whole book is going. You’re excited about a felicitous sentence, and you’re excited about the sound of a word next to the sound of another word, and that’s why you do it. But it’s a mix of back and forth.

Set in the mid-19th century, “In the Distance” follows a young Swedish immigrant who finds himself penniless and alone in California. As he moves east across the U.S. searching for his brother, he faces many harsh and inhospitable conditions and situations. What was the inspiration behind telling a tale of such vast loneliness and isolation?

I’m not entirely sure. I try not to think about that myself a lot. I think that everything I write has to do with isolation and disorientation to some extent, but mostly isolation … Even as an academic I was interested in that, but I find that if I ask about this too overtly, if I look at it too directly, I might break it.

So I think the answer to why I write about these things is, the books themselves are the attempt at trying to answer those questions … I think maybe it also relates to what we were talking about with Poe and Kafka. If you think about it hard enough —being a human being — doesn’t it in the end confront you with a certain sense of disorientation?

We’re not entirely sure why we’re here and where we’re going and what’s going on, like those are questions that have haunted humans forever. We’re also radically alone. We, of course, we live in community and hopefully we find love in our lives, but we experience the decisive things that are in our lives, and our death itself, completely alone.

And we are also confined and sequestered within ourselves, ultimately, and everything we do — and I include art and I include love and relationships — is our attempt at breaking through that, that solitude, and connect with others. And I won’t speak for others and say whether they succeed or not, but I think it’s a permanent struggle that speaks to our inherent solitude. And these are things that concern me, that I try to put in a less bombastic way than I just did right now in my books.

Your second published novel “Trust” explores themes of extreme wealth and power, and how these two factors can contribute to shaping a narrative — whether that is truthfully or otherwise. How does telling the story of “Trust” in its four metafictional parts — a novel-within-a-novel, an unfinished manuscript, a memoir and a diary — serve to enhance the novel’s overall message?

The notion of message in literature is a little suspicious to me. I have a hard time adhering to that because a message is something that is sort of conveyed. It has this kind of utilitarian dimension.

I think literature is sprawling and messy and thrives on ambiguity and a certain kind of happy sense of confusion. At least the literature that I enjoy. I like a certain kind of diffused lack of clarity, while sensing that there is control, that it’s not just a mess. But I think, when we talk about messages, we’re in the realm of efficient communication, which is not something that I’m into.

But to honor your question I would say that I was very interested in how power is reliant on narratives to perpetuate itself … Power really demands a certain kind of scaffolding that is verbal, that has to do with storytelling in order to exist. All forms of power surround themselves with a certain kind of storytelling paraphernalia. And that’s why censorship is so crucial to certain regimes, for example.

But so, for me it was, “OK, who?” Who gets to tell the story that later will become history? How are these stories told? By whom? From what place? Why are we more inclined and prone to take some stories to be more robustly anchored in truth rather than others? Why do we automatically associate certain genres with truth and excuse other genres to have that relationship to truth? Like we believe that historical document has more truth content than a novel, and we also believe that, I don’t know, a personal diary has more truth content about a person than a narrative about that person.

Needless to say I take issue with all of these things, and instead of presenting all these issues in a monographic way I thought, oh, wouldn’t it be fun to actually enact these different forms of storytelling, these different genres, these different points of annunciation, these different speakers, these different voices, and have readers feel what it means, like, to be touched, hopefully on your skin, by each one of these voices. And then engage readers in an active way in deciding, or at least examining their own presuppositions — like why was I more inclined to believe this version over the other?

“Trust” is featured on the New York Times’ 100 Best Books of the 21st Century list.

How did the idea of writing “Trust” in a four-part structure come to you? Or was it always the starting point for the novel?

No, it wasn’t. It was a long process of not knowing what shape the book would have. And then I think it came to me by thinking that wealth, (in) paraphrasing (Walt) Whitman, that wealth contains multitudes. Because any great fortune is the collection of, you know, the labor of all the people who made that fortune possible and whose work was ultimately expropriated in one way or another. That’s what a fortune is.

So I felt that to do justice to the theme of the novel — which is extreme wealth — there had to be a certain kind of polyphonic, choral quality to the book. And I didn’t know what that was going to look like. And then I realized, oh, maybe, maybe it will be a novel within the novel about the richest man in the world. And then I thought, oh, but maybe the novel is ghost-written. That was a very lucky day for me. And then it kind of took off from there. But it took a long time; it didn’t present itself to me in one single vision. I wish! That would have been so cool.

Among the many prestigious distinctions your writing has garnered, “Trust” won a Pulitzer Prize in 2023 and was also named one of The New York Times’ 100 Best Books of the 21st century. What does it feel like to just walk around as a person with these kinds of achievements?

It feels different considering, as I was saying at the beginning of our conversation, that for most of my life and writing life, I’ve just done this in total obscurity. So it does feel different. It’s very joyous and I don’t take it for granted. I don’t feel jaded about any of it. I’ve experienced the other thing, and this thing feels, you know, it’s a wonderful, fortunate thing that happened, and I still can’t believe it. It’s really great.

At the same time, it would be disingenuous of me to say that it doesn’t come with a certain amount of pressure and expectations. And that is real. And also the truth is that when I’m writing, all of that fades away. It’s really about the work. And writing as beautifully as I can, and writing the most heartfelt prose that I’m capable of. And there is no room for other considerations at the time of writing.

How do you know you’ve landed on the right idea or the right inspiration that you can craft a whole book from?

Each book feels very different, and sometimes it’s very clear from very early on. I normally read a lot toward each project before I start really writing. So if it feels like a chore to read novels or nonfiction or historical documents, whatever it is toward a book, if it feels that I’m bored, then I know it’s doomed.

And then I suppose, once the writing starts, if I feel the idea is strong enough for me to overcome the first really atrocious attempt then I stick with it, because it’s always terrible when you start. So if I love the project enough to keep going through the nausea that I feel looking at my awful sentences, then there’s probably something there.

Do you have anything new in the works now?

Yeah, I just submitted my book to my publisher. I’m waiting to hear back with her notes. There is no publication date, but there is a whole novel (laughs).

Any advice for aspiring writers?

Well the first one is very commonplace: read. I’ve been traveling so much across the world, meeting with young writers in different countries and from different backgrounds. And it’s very shocking to me that sometimes some of these aspiring writers are not readers, which, I don’t even understand why you would want to become a writer if you’re not an avid reader to begin with.

But I think that is the way to learn how to craft, how to understand what it is you want to do, and measure yourself against other authors and think, Oh, I wish I could do characters like George Eliot … I wish I had Joy Williams’ sense of humor, and at the same time metaphysical depth and levity, and so on and so forth … Only you will know what the right direction is. So that’s the first thing.

Fall in love with language that happens through reading; there’s no other way. And then allow yourself to suck on the page. Allow yourself to be awful. It doesn’t matter. And keep going. Allow yourself to fail, is what I’m trying to say. But also know that writing — if you’re living literature, really — writing doesn’t always happen at your desk. Trust the moments when you’re away from your desk because things happen in your brain. But be hungry. Be avid. Be open and allow yourself to feel. And go for walks.

Have you been to Tulsa before?

I’m very thrilled to visit Tulsa. I’ve traveled extensively throughout the entire United States, but for some reason Tulsa has eluded me. I don’t know why. So, very excited to rectify this terrible error.

Rapid fire book questions: What’s a book you always find yourself returning to?

“Moby Dick.”

A book you often gift others with?

“This Is Not a Novel” by David Markson

What book are you wanting to read right now?

Exactly the book I’m reading. I had never read “Emma” by Jane Austen. I’m halfway into it, and I can’t believe how fantastic it is.

Tickets can be purchased at tulsalibrary.org/helmerichaward

Source link