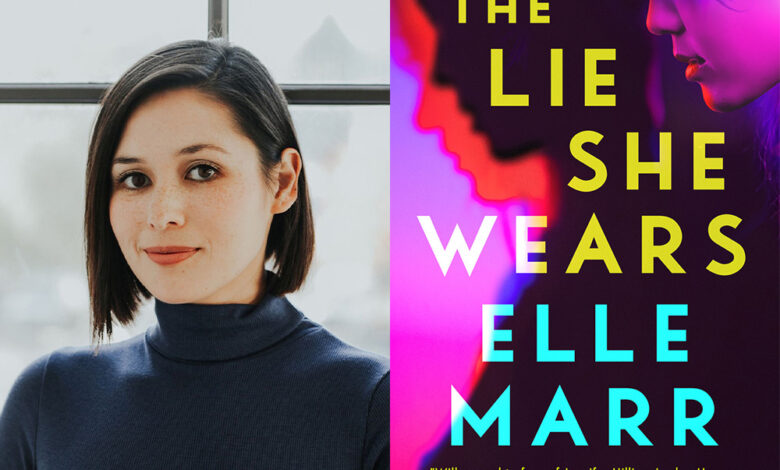

Q&A: Elle Marr, Author of ‘The Lie She Wears’

We chat with author Elle Marr about The Lie She Wears, which follows a daughter who inherits her mother’s deadly secrets in a chilling novel of psychological suspense. PLUS you can read an excerpt at the end of the interview!

What inspired you to write THE LIE SHE WEARS?

I’ve always been fascinated by the art world. When I found myself dwelling on the research I had done while writing The Alone Time, which features a character who specializes in post-modern art, I knew I wanted to explore that world more in my next book. I began to think about art museums and what kind of person would become an art curator, what would drive them to study something at such length, while knowing that an object’s entire story would perpetually be out of reach.

A recurring theme in your work is family trauma. What draws you to this particular theme, and how does it play out differently from your previous books?

Trauma is a recurring theme in my stories because it’s a universal facet of life. No one escapes this world without some jarring event or conversation that stays with us, that returns to us when we’re lying in bed, trying to go to sleep. In THE LIE SHE WEARS, my main character Pearl explores a softer kind of childhood trauma, that is in no way less potent: neglect. She is constantly battling the messages she internalized at a young age, even to the point of imagining her mother Sally’s belittling voice after her death.

Without giving too much away, you turn the tables on the typical male serial killer role in this new book. What drew you to this idea?

In the past, film and books have hyper-focused on male serial killers—a trend that continues in the media today for certain valid reasons. But in my research while writing my previous books, I learned about the traits of female serial killers, and also how underreported their numbers can be. I wanted to explore our assumptions as readers, then turn them on their head.

Your protagonist is a museum curator, and your descriptions of Pearl’s work are so evocative. What’s your take on research, and how do you do it?

Research is a must during any book that I write, but I rarely undertake huge trips for the sole purpose of researching a premise. Instead, I’m constantly documenting and exploring ideas, places, or events that stick with me. In a way, I’ve been researching art museums since falling in love as a child with the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California, where I grew up; whenever I’m in a new city, I make it a point to visit the local offering, and have been lucky enough to hit many major museums globally. For this book, delving into the world of an art curator’s perspective was pure fun. But it was also educational in that I was able to examine primary and secondary sources online, and I was lucky enough to speak to the art curation team at the Portland Art Museum and learn more about their practices. Discovering the Smithsonian’s published guide to art curation was another highlight for me.

Why is representation of AAPI stories so important to you?

I grew up without a lot of Asian-centered stories on my bookshelves. I didn’t see them available in my local bookshop, or on my TV, and as a result it seemed like my culture wasn’t as valuable or important. That has changed considerably over the years, and I’m so honored to add to today’s more diverse, mpdern options now.

Who was the most difficult character to write, and why?

Sally, Pearl’s mother. She is particularly flawed, having survived a difficult childhood herself and ultimately carrying those scars with her into motherhood. I needed her to be someone with whom the reader could sympathize but also readily believe the complicated loathing that Pearl feels for her. Sally is an enigma, as many mothers are to their children at the outset. The subtle forms of neglect and abuse that she wielded on Pearl added layers to their relationship that required some nuanced wording on my part.

Your book had so many surprising plot twists, I was honestly shocked even at the very end. Do you figure out all of these twists and turns ahead of time, or do they come about as you are writing? Can you tell us a bit about your writing process?

This book was a trip! I thought I knew the ending and wrote about three different versions of it. The final chapter kept changing based on what was most top of mind for me at the time of writing, during the final six months of 2024. I usually map out the major twists and turns, but this book was firmly in control during the drafting period. Every time I thought I knew what was going to happen, the characters pointed me in a different direction. While I love how THE LIE SHE WEARS turned out, it had a much more dynamic writing process than my previous books.

What do you hope readers will get out of reading your book?

This book is about growth. Each of my characters goes on a journey to understand themselves better; some are more successful than others, while one refuses any introspection at all. Although the heart of this story speaks to the mother-daughter dynamic, I hope readers will recognize the underlying dangers of emotional stagnancy.

Do you have a favorite quote or scene in THE LIE SHE WEARS that you find yourself going back to?

There’s one scene wherein Pearl is questioning her mother’s best friend, urging the friend to spill details from Sally’s life. The friend replies, “Can’t a mother have her secrets, even in death?” This echoes the theme of the mother-daughter conflict that quietly dominates most of the book, though as a shadow from the past. I also love one of the major twists in this book, nearly at the end. Since to talk about it would be to spoil it, I won’t. But it’s one of my favorites that I’ve written, and is a complete game-changer to the narration.

How did you decide on your book’s title and cover design?

For the title, I wanted something evocative of both the figurative lies that we inadvertently (or intentionally) wear when occupying different social circles, and literal masks to highlight their role in this book. Most people adjust their behavior to accommodate their environment in ways that we would find reasonable. Some, however, take it to extremes. The cover design was meant to suggest the many faces that my characters adopt in this story.

Were there experiences in your personal life or career that came in handy when writing this book?

My grandparents used to collect masks, similar to those that Sally does in this book. I always thought they were beautiful, but occasionally terrifying to behold in the middle of the night. The empty eye holes and glitter that marked each of them in some way struck me as sinister yet hypnotic. I definitely drew on my real memories of tense, midnight walks to the bathroom, and tried to imbue this story with Pearl’s alternating appreciation of these masks and her fear of them.

What advice or words of wisdom do you have for fellow writers – other than run!?

Don’t undertake this writing thing lightly; come to the table with your ideas prepared—and at least well considered, if you’re not into outlining. I think everyone’s process is valid (lots of writers I know are pantsers); but for anyone struggling with time management, mentally preparing yourself in advance to write a story is so key. Most of us write because we love it, right? Lean into that and don’t forget it. Especially on the hard days when the words are stubborn.

EXCERPT

Chapter Two – PEARL

Everyone harbors secret fears. A creature under the bed, a stranger following us home, an image burned into the mind’s eye from a horror film viewed at a too-young age.

Not everyone chooses to specialize in their fear.

Plywood shipping boxes, plastic containers, and high-tech steel-reinforced cases overflow the storage docks of the windowless warehouse hall. Shoddy light bulbs flicker overhead, casting ominous shadows at nine in the morning. I usually avoid doing this task on my own, but I set my shoulders and clomp forward in my asexual flats anyway—essential footwear for any woman in historical studies. Gunmetal-gray scaffolding extends for rows from the doorway where I entered. The numerous aisles still fail to convey the extensive backlog of artifacts, waiting to be chosen for display in one of the museum’s many exhibit halls.

As associate curator, I should be more comfortable searching through the wooden crates and plastic bins, perusing the white sticker labels slapped on top that often include notated shorthand and country abbreviations. But this is my first real museum job as a hired expert—no more seeking coffee orders as an intern—and, until now, most of my time has been spent researching my subject. Griffin, my boss and chief curator of the museum, has been dangling a promotion over my head since I was hired six months ago. I need to get this right, even if it means staring at the source of my childhood nightmares.

A Tibetan mask painted black with white spirals jeers at me through a plastic storage crate. I shudder, turning away.

“Pearl, right? What’s your poison?”

A man emerges from the third row to my right, wearing blue coveralls and holding a box from this morning’s delivery from Seattle.

Xander, the director of collections, sports a too-chipper grin, considering the ghosts surrounding us.

I return a smile. “Twelfth-century China.”

He clicks his tongue, bowing slightly as he flattens a hand across his chest. “Right this way.”

We pass an endless series of tools, then turn right midway down the hall and along older rusted shelves. A laminated sign announces we’re approaching Islamic art as our footsteps echo against Neolithic pottery shards, plaster casts of Greek busts, and other items from the epochs that museum curators deemed too disparate to form a collection worthy of display.

When I was first hired as associate curator of Asian art, I was elated. Thrilled that my PhD in Art History from Stanford wouldn’t go to waste and that I’d be one of the youngest associate curators on record at the Portland Art Museum at twenty-seven. I was so excited to share the news with my mother Sally, who first seeded my love of unrestored tapestries found in thrift stores across the greater Pacific Northwest. Then I learned my chief task would be to cobble together an exhibit with zero budget in time for the Halloween season, when it’s taken me six months to understand the museum’s existing inventory. Sally wasn’t impressed by my new job. When I shared the news, she spilled her tea across the counter, deliberately, then told me to clean it up.

But that’s a bygone worry now. A bittersweet memory, I suppose.

A woven straw doll glares at me from a clear circular bin and an aisle dedicated to the Chinook. What are you looking at?

After my mother Sally died in a car crash four weeks ago, Griffin told me I could take as much time as I needed to process the loss. The offer lifted some of the depression cloud that had been following me. Had been trailing me since Sally’s diagnosis of cognitive decline.

“The next two rows should offer what you need.” Xander gives me a thumbs-up. “You excited for the unveiling of the new floor?”

“If by ‘excited’ you mean terrified, yes.” I offer a smile to soften the vulnerability of my joke, but Xander doesn’t laugh.

“Sure. I was too for my first big project.” He nods. “You’ll do great.”

I murmur my thanks as he goes, feeling as awkward as when I started back in April, when something scrapes in the aisle behind me. I turn toward the sound. But only shelves of dusty crates face me in response. The aisle extends another fifty feet, replete with half-empty receptacles. Deteriorating fabric swatches in need of restoration are visible through certain containers, along with thick plastic-wrapped tableaux, ancient paintbrushes, and ornate headdresses.

You never cared this much about anything, lazy.

I step forward. Closer to my quarry. A heavy metal door slams shut from the southmost corner of the room. Although the Portland Art Museum offers over 100,000 square feet of gallery real estate, the storage areas occupy another quarter of the property. So many discarded relics that will wait years to see a patron.

You care more about this than you do your own mother.

I clench my jaw, fighting the urge to argue. Force myself to focus on the labels instead of the haunting echo of my mother’s voice. The first week after Sally’s death was the hardest. I stayed in my apartment most days, sitting alone on the love seat in front of a Netflix marathon. Then, after the funeral, I started imagining her voice in some twisted form of masochistic grief, whenever I began a risky task or project that I knew I wasn’t ready for, like cleaning out the gutters of the ranch house. The knee-jerk habit of conjuring up my mother’s most disappointed comments has only grown more frequent, more poisonous, recalling her frustration with me. Though I know I’m in control of my thoughts, and even the ones that resemble Sally’s oft-voiced opinions of me, the memory of her angry tone is a shock when I’m feeling exposed.

I follow the labels, now only haphazardly listening for the scraping noise. At the end of the aisle, where the shelves nearly touch the back wall, the years progress to reach the twelfth century and span the continent until “China” is legible in black ink against white adhesive.

“Gotcha,” I whisper. “Now who’s lazy?”

When I learned there were over four thousand items of Asian art gathered here, ranging from historical to contemporary, from South Asian to East Asian and everything in between, my chest tightened. As if spring cleaning had arrived yet again and my mother had banished me to the attic to organize the plastic rice bowls she saved across two decades. I was overwhelmed at the thought of how to highlight so many in an exhibit—how to prove myself to my employer in this make-or- break moment of my budding career.

Then I recalled the foundation for my interest in museum work. The catalyst to every random roadside antique store pit stop my parents made during family trips, and the motivator that made midnight visits to the bathroom a harrowing experience in our hallway: masks. Asian cultures, across countries and regions, have employed a decorative and practical range of facial coverings. My first exhibit could be no different.

Do you really think you can do this? You barely finish your dinner.

I pause before stacked shelves of preserved jewelry and headpieces. A quick scan of the content labels confirms this might take a while. The only way to tell whether the boxes house the masks I need that relate to twelfth-century China—when opera and funerary masks were in common use—is to crack each one open.

“Good thing I had caffeinated boba today,” I murmur.

The first three crates reveal early on that they’re not what I need. The fourth—sourced years ago, judging from the black scuff marks around the opaque base—provides a half dozen Jing masks from the seventeenth century. A solid win, though not my target era. The painted and patterned masks, still commonly employed for Chinese opera performances, come with newspaper that dates from 1962 lining the bottom of the bin. A reminder of how long this museum and my predecessors have been hoarding items without properly cataloging them.

Something scrapes again from the next aisle over. A box? I pause shuffling the crisp strips of paper. I thought I was alone.

Lifting my head, I make eye contact with a face, then startle backward. My throat constricts before I register the mask peering from the bin on the next shelf up. A Buddha with fat cheeks and a lolling tongue. Empty eyes return my stare without blinking.

You don’t even know what you’re doing.

I exhale a long, controlled breath. Shake my head at the way I leaned into the jump scare. “Literally could have chosen anything for my dissertation. You did this to yourself, Pearl.”

Scrape. Scrape. Scrape. That noise again.

I reach for my phone from my back pocket. Tap the flashlight option on the home screen, then slide my feet toward the end of the aisle, eyeing the floor for darting four-legged bodies. Rats and other rodents are common to museum storage spaces—hazards of cool, dimly lit environments meant to protect and preserve artwork and cultural objects.

“Hello?” I say. “Anybody there? Xander?”

A shrill chime erupts from my hand. The name of my mother’s estate attorney appears at the top of my phone screen. The attorney with whom I scheduled a meeting that started fifteen minutes ago. “Shit.”

“Hi, Mr. Singh,” I answer, my pulse still amped. “I’m so sorry—I know I’m late.”

“Hey there. Just wanted to see if now still worked for you.”

I nod to a bamboo scroll beside me, to its faded, curling calligraphy. “Yup. I’ll be there in ten.”

Will you be picking up The Lie She Wears? Tell us in the comments below!

Source link