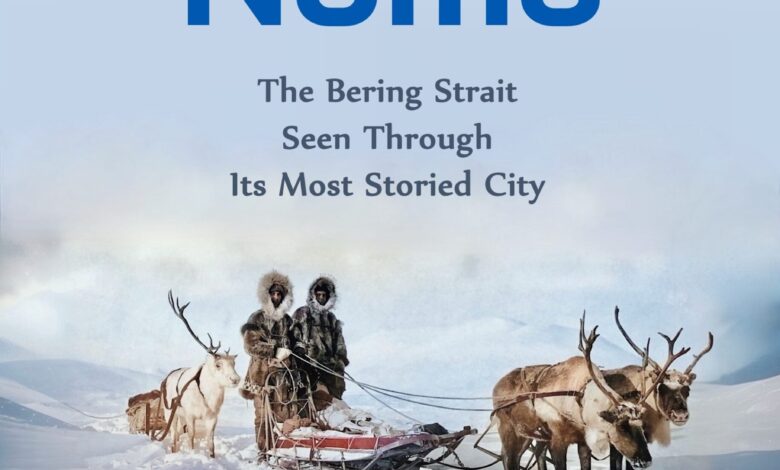

Author’s Deep Dive Into Alaska’s Far Out Town

The following appears in the October issue of Alaska Sporting Journal:

Mention Alaska and your first thought might be of iconic salmon runs heading up pristine rivers, massive big game animals like bears, moose and caribou sharing the Last Frontier with its people, and perhaps endless summer daylight that describes the “Land of the Midnight Sun.”

And there’s the Western Alaska city of Nome, a tiny, hearty and historical melting pot of a community of just under 4,000 hard on the Bering Sea’s Norton Sound.

Nome is now known for its isolated location, dreary winters and gold dredging vessels made famous by the Discovery Channel series Bering Sea Gold, but it also has a colorful past – both in good and bad ways – that one-time Nomeite and author Michael Engelhard was fascinated by.

“In truth, Nome’s contrasts at once can jar one and stimulate thought. There is racism, poverty, femicide, domestic and substance abuse. There is laughter, beauty, resilience, and vibrancy, too,” Engelhard writes in a new book that captures whatever perception you might have about this quintessential Western Alaska town.

Trained as an anthropologist with a degree from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Engelhard worked

for 25 years as a wilderness guide and as an outdoor instructor. His books include the National Outdoor Book Award-winning memoir Arctic Traverse (see our August 2024 issue), the cultural history memoir Ice Bear, and the essay collection he’s published now that discusses, among other things, how dwindling caribou herds around the turn of the 19th to 20th century made reindeer herding big business, even amid Nome’s gold rush heyday chaos.

The following is excerpted from No Place Like Nome: The Bering Strait Seen Through Its Most Storied City, by Michael Engelhard and published by Corax Books.

BY MICHAEL ENGELHARD

“THE DEER IS LIKE MONEY”

In July 1897, among a sales ad for walrus heads and news of the discovery of antique Eskimo armor made from iron slats, the following appeared in The Eskimo Bulletin: “The success attending this year of the mission herd of domestic reindeer at the Cape [Prince of Wales] speaks well for the faithfulness and skill of our Eskimo herders, all of whom are Christians. Each of them has driven more than 500 miles during the winter.”

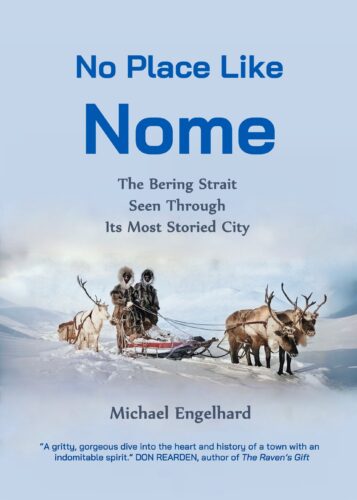

The author and publisher was William Thomas Lopp, teacher at the Congregational mission and, briefly, superintendent of the Teller Reindeer Station. The wintertime long-distance reindeer driving had been done entirely in reindeer-drawn sleds with the driver balanced on the runners, dog sled-style.

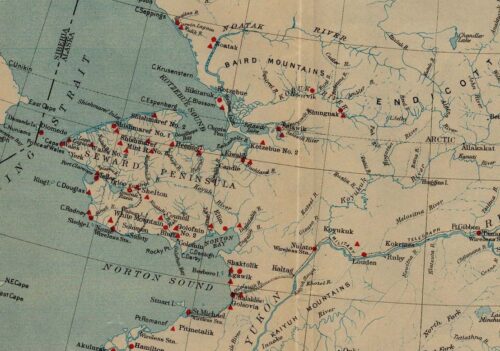

Only five years before, on Independence Day, the Teller Reindeer Station had been established, with flag raising, cheering and 53 Siberian reindeer landed at Port Clarence, the only sheltered port on the Bering Strait coast. This breeding stock laid the foundation for a total of 640,000 reindeer on the Seward Peninsula and would shape the welfare and livelihoods of its Alaska Native residents for the next 40 years.

BY THE END OF the 19th century, commercial hunting had depleted the region’s whale, walrus and caribou populations, and starvation haunted the coastal Iñupiat. Following his belief that “God blesses aggressiveness,” the Presbyterian Reverend Sheldon Jackson – Alaska’s General Agent of Education – had made five trips to Siberia in 1892 and imported 171 reindeer to aid Western Alaska’s Native residents. Four Chukchi Siberian men accompanying the initial shipment were employed as herding instructors. Iñupiat traveled from hundreds of miles away to determine what the white men at Teller were up to.

Jackson used herding as a means for teaching Alaska Natives of both sexes modern domestic skills, English and math, so they could do business with whites. But Jackson had another agenda: Manifest Destiny. Not only would reindeer turn hunters into herders, he thought, but also “utilize hundreds of thousands of square miles of moss-covered tundra … and make these now useless and barren wastes conducive to the wealth and prosperity of the United States.”

For ages, however, this “barren waste” had meant security to people who were not ranchers, miners, or farmers. Their crops were the North Country’s wild animals. “Any time that we wanted an ‘apple,’” said Iñupiaq leader Eben Hopson from Barrow, “we went out and got it. We got what we wanted to live on, got what we needed.” But the locals fast-learned the new economy. “The deer is like money,” one herder observed.

Selected by the mission teachers, Iñupiaq “apprentices” (boys or men) got five years of schooling, together with room and board. The first year, an apprentice earned two of the reindeer in his care, the second year five and the third year 10. After five years, a herder was loaned enough reindeer to increase his herd to 50 animals.

From the beginning, tensions flared between the missionaries and the Chukchi, who when thirsty, lassoed a reindeer doe to drink directly from her teats, “quaffing it with as much enjoyment as if it had been pure nectar.” More offensive to their supervisors was the Siberians’ practice of guiding the salt-loving reindeer by marking the ground with streams of urine. Such behavior, in the eyes of the missionaries, would do nothing to help civilize the local Iñupiat.

In 1894, the missionaries recruited 16 Saami in Lapland to replace the Chukchi as herding instructors. A Christian role-model clause in their contract bound the Saami to behave “orderly and decently and to show discipline.” Each Saami herder received 100 deer for three to five years of service. The local Iñupiat soon warmed to the newcomers, calling them the “Card People,” because their traditional Four Winds hats reminded the Iñupiat of kings’ and jacks’ headgear on playing cards. The Iñupiat herd-ers-in-training were less happy with their subordinate status, the monotony of the work compared to fishing and hunting, and the lack of immediate payback.

THE WINDS OF OPPORTUNITY blew a family into Nome that would become its richest, shrewd promoters of reindeer meat as well as the Christmas holiday, especially Santa and his sleigh. In 1903, Carl Lomen and his father, Judge Gudbrand J. Lomen of St. Paul, Minnesota, moved to Nome after a working vacation there at the height of its gold craze. Carl’s mother, four brothers and one sister soon followed. Lomen senior hoped to profit from disputed mining claims but ended up forging a corporation with several backers: Lomen & Company.

Carl’s first encounter with reindeer paints a rather citified picture of him. Wandering the tundra near Nome in the summer of 1900, he came upon a herd and froze in his tracks. He was ignorant of reindeer habits and feared they might attack.

Conflict over the best rangelands soon mounted. Eventually, Lomen controlled the prime grazing grounds, charging Eskimo herders a use fee and collecting a herding fee for each Iñupiaq reindeer that got mixed up with his herd. While the Lomens hired Native herders and bought their excess steers, these were largely token gestures. Still, with breeding stock from firmly established mission herds, new reindeer stations sprung up in Iliamna, Barrow, Kivalina, Nulato and as far inland as Bettles.

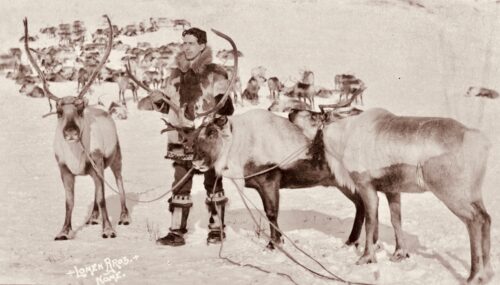

deer leg. The widow of a Teller Reindeer Station trader, Mary once owned the largest herd in the North Country. “Mary adopted 11 children, some of which had been orphaned by the epidemics. She trained them and other Iñupiat to become ‘deer men,’” the author writes of one of Nome’s many colorful historic figures, “and soon they ran herds of their own.” (ALASKA STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES)

Some Iñupiaq herders benefitted, if only temporarily. One of them was “Sinrock Mary,” born in 1870 to a Russian trader and an Iñupiaq mother as Changunak, who would become trilingual and eventually accompany Healy and Jackson, sometimes to Siberia, working as a linguist and interpreter.

She would later become known as the “Reindeer Queen of Alaska.” Raised in St. Michael, she married the Teller Iñupiaq herder Charles Antisarlook in 1889, and the couple moved to Cape Nome. Charles had already built his own modest herd, the first to be owned by an Alaska Native. When he died from measles in 1900, Mary fought and succeeded in keeping her half of the herd. She started to sell meat to local businesses and the Army station. Her second husband was not interested in reindeer, so Mary adopted 11 children, some of which had been orphaned by the epidemics. She trained them and other Iñupiat to become “deer men,” and soon they ran herds of their own.

At one point, “Queen Mary’s” herd was the largest in the North, but she kept living simply fishing, gathering berries and greens, and preparing skins for sewing. A Swedish schemer claimed to be her third husband in an attempt to disown her. Changunak had long witnessed the effects of disease and unlawfulness upon her people. Miners staked claims inside grazing ranges, and reindeer were lost to rustling. Clearing claims by burning the tundra’s vegetation deprived reindeer and caribou of forage. In addition to encroachment upon Native hunting and fishing grounds, new diseases preyed upon people – smallpox, influenza and measles. Over half of the Native population in Northwestern Alaska had died by the end of 1900, a mere two years after the mad rush for gold had begun. ASJ

Editor’s note: You can buy the book at https://www.amazon.com/No-Place-Like-Nome-Through/dp/B0DX4ZGLJT or at your local bookstore. For more on author Michael Engelhard’s other books, check out michaelengelhard.com.

Sidebar: A LIVING TRADITION

During the 1960s, Alaska Native owners were selected to become private reindeer herders with designated ranges. In 1968, the Bureau of Indian Affairs took over range management by issuing grazing permits and monitoring range conditions. Soon after, modern range management techniques, in part developed with the University of Alaska, Fairbanks Reindeer Research Program, were applied to herding. With passage of the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, Alaska Natives were drawn deeper into free enterprise, and several regional and village corporations sought to revitalize reindeer herding as viable economic ventures.

Currently, there are approximately 20 reindeer herders and 20,000 reindeer in Western Alaska. These herders belong to the Reindeer Herders Association, part of the Kawerak, Inc. Natural Resources Division. This group provides assistance with improving herd management and developing a viable reindeer industry to enhance the economic base for rural Alaska.

Some modern herders use satellite collars to locate their herd, and at summer roundups near Teller a helicopter – hovering 8 feet above the ground – helps funnel reindeer into corrals. The pilot is Donald Olson (Iñupiaq), a medical doctor, Alaska state senator, and also the great-grandson of one of the original Saami herders. Nowadays, the most lucrative reindeer product is velvet from the new antlers, a homegrown Viagra for Asian markets. ME

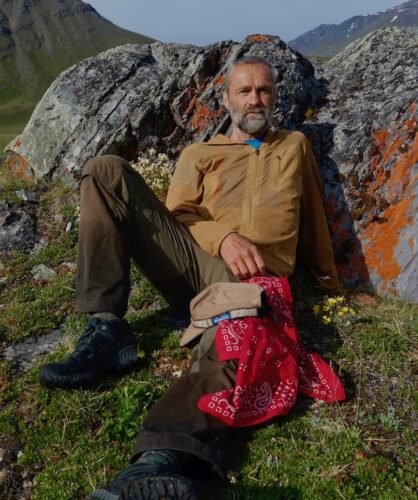

amenities might also get to people,” says No Place Like Nome author Michael Engelhard, who lived in the remote city along the Bering Sea for three years. “You have to live in Nome for a while to see and appreciate its true character and that of its people.” (MELISSA GUY)

Q&A WiTH NO PLACE LIKE NOME AUTHOR MICHAEL ENGELHARD

Alaska Sporting Journal editor Chris Cocoles caught up with No Place Like Nome author Michael Engelhard on what makes this community such a “storied” city.

Chris Cocoles Congratulations on this latest book, Michael. What was your inspiration for writing about Nome?

Michael Engelhard I lived for three years in Nome, and as the book’s subtitle says, it is the most storied city I’ve ever lived in. Positioned at a crossroads of continents and cultures – North America and Asia, Anglo and Iñupiaq – it is rich in characters and history dating back at least 15,000 years, when people traveled there from Beringia, the land bridge now submerged. Over the years, I’ve written articles about Nome and the Bering Strait for various magazines and, realizing that there was much more material waiting to be explored, I decided to more fully portrait the town and region.

CC What an historic, fascinating, complicated, if not at times tragic, backstory Nome has. Can you put into words what the research was like for you working on this book?

ME The book was largely written while I no longer lived in Nome, and with the multitude of facts, checking each one personally was beyond my reach. Plus, frankly, there can be ideological divides in Native communities about conservation versus development, for example; the same as in any society, really. Orally transmitted stories are another good example: Different versions usually coexist, so it’s impossible to find the “true” or “official” one. I tried to double-check the correctness of facts, usually from not one but several sources. The University of Alaska Fairbanks’ oral history department has done incredible work interviewing elders and recording them, and I used those archives, plus visual sources (old photos, film clips, etc.).

CC Probably the first time I ever heard about Nome was the movie Stripes, when the obnoxious Army Captain Stillman gets banished to a command in Nome. Do you think that’s the perception people have for Nome – that it’s a dreary place you don’t want to end up in?

ME That may be the case. It doesn’t have the scenic values of, say, the Alaska Range. It’s a more subtle beauty of tundra and rolling hills – though they have the Kigluaik Mountains near town, a 48-mile miniature Brooks Range of peaks up to 4,714 feet above sea level. Some people rock-climb there. It can seem forlorn on overcast days, with the gray sea as backdrop and the wind howling. And it is almost always blowing. Being without big-city amenities might also get to people. You have to live in Nome for a while to see and appreciate its true character and that of its people.

CC As you describe in the book, gold is a huge part of Nome’s identity. Can you explain a little bit about that connection?

ME In 1899, after the gold fields in the Yukon’s Klondike had all been claimed or exhausted, the “Three Lucky Swedes” (one of them was actually Norwegian) struck it rich on Anvil Creek. The town originally was called Anvil City, after a rock outcrop on a nearby mountain. So, the action then shifted to Nome, which could be reached much easier, by steamer, rather than over the arduous Chilkoot Pass from Skagway or up the Yukon River from its mouth at St. Michael. Some Sourdoughs in Dawson even hit the trail on bikes and rode on the frozen Yukon River all the way to Norton Sound that first spring. Even latecomers still had a chance to make money from the “Poor Man’s Diggings” – Nome’s beaches, which hold gold-bearing sands and could not be claimed individually. That’s where also much of that current reality TV show takes place – Bering Sea Gold – on the beach and offshore, where amateur miners on pontoon boats dredge up the ocean floor and sift it mechanically.

CC The other component that defines the city is dog sledding, including the Iditarod connections. How important have these remarkable working dogs and their mushers been to the people there?

ME There are no more “working dogs,” per se, in the region, but Nome definitely remains a dog town. The Iditarod brings in big revenues from tourists and journalists who come to watch the finishers on Front Street. But the race has lost some of its luster. Many of its sponsors are now corporate or backing out over allegations of animal cruelty; the race start last year was moved to Fairbanks, north for the fourth time, since Southcentral Alaska snow at its start was in short supply again; and most Nome mushers no longer exercise teams on the Iditarod Trail for fear of getting hit by a snowmachine.

CC Alaskans are known for their toughness, but does a Nomeite have to be even more resilient than a typical resident of the Last Frontier?

ME I don’t think they are tougher than rural Alaskans elsewhere (though they might like to believe so). They are just facing challenges that differ from those in other places; many of those are logistical. All fuel, heavy equipment, construction material and trucks have to be barged in during the summer, for example, and storms can delay those shipments. The town also experiences some pretty serious flooding during storms, and blizzards that create rock-hard snowdrifts, which bury roads. The Native cultures, before first contact, however, had adapted to this harsh environment. As people sometimes pointed out to me, their ancestors really were tough.

CC What’s the fishing and hunting scene like in Nome?

ME The fishing is good, though not by Southcentral Alaska standards. There are salmon and Dolly Varden at the mouth of the Nome River, and some starry flounders. But it’s, of course, best known for its crabbing; Bering Strait king crab is simply to die for. The hunting isn’t the best. Not a lot of cover for moose, and bears and caribou are scarce in the area. (Perhaps still from overhunting during the first gold rush and commercial whaling times?) On the other hand, you can see muskoxen right in town, sometimes near the Alaska Commercial Company store, where they play “King of the Hill.” You can also see them grazing right by the runway while planes take off. I think they may hide from prowling grizzlies in town, somehow knowing that they can’t be hunted within city limits. Beyond those, it’s a different game, and you can see muskox skins drying on people’s porches.

CC You did a deep dive into some of Nome’s most interesting personalities like wildlife author Sally Carrighar, photographer E.S. Curtis and missionary/reindeer herder William Thomas Lopp. Did they really help you understand the soul of Nome?

ME I think so. It is vital to link the past with the present. The two are not sovereign countries; we have one foot in each. History first and foremost is storytelling, and the stories of these famous individuals (and a score of lesser-known ones) helped me to understand patterns. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “All history becomes subjective … there is properly no history, only biography.” The fable of the elephant and the blind men, in my opinion, gets it wrong: A bigger understanding does hide in the sum of smaller ones; in this case, individual lives.

CC What’s one very overlooked component of Nome that we should all know about?

ME If anything, I’d like readers to acknowledge that this is not an American backwater and never has been, and that history there reaches so much deeper than the 1899 gold rush, when “Anvil City,” as Nome was then called, was founded. With the newly developing geopolitical situation and the Northwest Passage now largely ice free, Nome and the Bering Strait might well become hot spots again, as they were during the Cold War and even during the Russian period.

CC Is there an only-in-Nome story that stands out to you from writing the book?

ME There are so many. Stories nest within stories there, like Russian dolls. But here are some glimpses that for me perfectly capture the spirit of Nome: On a cold, stormy early summer day, I was beach walking with my wife. Some Iñupiat kids were out swimming and frolicking like sleek seals, amid bergy bits of sea ice. During the 2011 “blizzicane,” I saw kids riding BMX bikes into rough surf. I really admire that kind of spirit and hardiness. Nomeites have strange customs, too. After Christmas, people put their trees out on the sea ice (when there is any) and call that the “Nome National Forest.” (The town is surrounded by treeless tundra, which feels more arctic than subarctic, culturally and biologically, though it lies at roughly the same latitude as Fairbanks.) CC

Source link