Dead Ringers | Walker Mimms

The first time I saw a sculpture by Tatiana Trouvé, in an uncommonly dim gallery at a museum in Mougins, in southern France, I assumed that I had found three blankets stacked tidily on a chair, supporting a book. The piece was called The Guardian. It was, I would later learn, one of a series by that title. Other iterations include chairs or stools propping up stacks of suitcases, reading material, and the like, with certain items maybe wedged into the pile—a shoe, say. Here, it seemed, was an artist who arranges unassuming piles of stuff, like Damien Hirst or Tracey Emin used to do.

If anything can be art, it has to be clever. Blankets? I passed. On my way back through I saw the trick. Those textiles that looked so fluffy and buoyant were in fact carved granite and marble. The stool was bronze, its rungs distressed in patina as if by years of heels. I’d been genuinely had, by some of the most impressive photorealism I had ever seen.

Trouvé’s craftsmanship is the opening gambit—but only the opening—of a large and startling retrospective that recently closed at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice. There were about seventy-five sculptures, some of them installations of hundreds of pieces, many of which a janitor might unknowingly sweep up, like the custodian who threw away a Hirst installation of ashtrays and beer bottles at the Eyestorm Gallery in London in 2001. (“I didn’t think for a second that it was a work of art,” he told The Guardian, vindicating conservative museumgoers everywhere.) There were also 150 works on paper, mostly small studies or Covid-era lockdown drawings, but also some very big, atmospheric, painterly drawings with scenes apparently set in galleries, and mounted on canvas. I found them to be smoke breaks from the demands of the sculptures. “Comestibles,” as James Turrell calls his prints.

In the sculptures, the game is likeness. Some Guardians sit on bronze quilted “blankets,” polychromed into dead ringers for the real, blue things you should pad an armoire with when you move. One unwieldy piece from a series called Notes on Sculpture stars brooms with individuated bristles, wedged among tall tangles of construction-grade tension cable—again, very illusionistic rust-painted bronze—that’s been hung with coat hangers carved from marble and crammed with cast detritus: cigarettes, a matchbox mid-spill.

So much time, so much money. The payoff of Trouvé’s work is the way it perverts our understanding of monuments. Since her sculptures speak the language of memorialization, you might expect them to be about the objects they seem meant to commemorate—all their rich patinas, all their fine stone gleaming like mortadella or milk-glass. But stare long enough and all you see are all the accidental forces that might lie behind these scenes. The objects in Nelson (2021), a few racks hung with coat hangers in marble and onyx and shopping bags in marble and bronze, seem to know perfectly well what they’re up to—who hung them there and where they’re headed and why, and who Nelson is—even if you don’t.

When she makes you “see through” her objects in this way, Trouvé is transcendent. She called the show “The Strange Life of Things” because, I think, she understands the tricks that time and memory play even on the most enduring materials. We commemorate things in stone and metal because we flatter ourselves those materials will last. Unless Venice really sinks, Verrocchio’s equestrian statue of the captain-general Bartolomeo Colleoni could stand another five hundred years. But how many people today remember Colleoni’s victory at Brescia? We remember the folds in the neck of the bronze horse he rides.

If your name is “Trouvé,” or “found,” it means that someone in your ancestry was raised in a French state home for trouvées—orphans. This Trouvé was born in 1968 to French and Italian parents, raised in Senegal, and art-schooled in the Netherlands and in France, where she now works. Represented by the mega-gallery Gagosian, she has shown in America rather quietly, most publicly in a Central Park commission of 2015, a rack of spools representing the paths in that park, which was high in concept but low in visual beauty.

That was before she honed the impressive vocabulary on view in Venice. Her practice these days (as dealers call it) consists of collecting items from her life of no particular nostalgic value, then casting them one by one in silicon, at her Paris studio, for future replication at Fonderia Nolana, a foundry in Naples to which she decamps for weeks at a stretch when it’s time to finish new work. A room-size installation in Venice arrayed thousands of components, in bronze and marble, awaiting future use: dried flowers, old padlocks, tin cans, spools of wire and Marseille soap, dried lizards, hairclips. And many books, each with a crisp, laser-cut author and title: tomes by anthropologists (Deborah Bird Rose), novelists (Le Guin, Eduardo Lalo), economists (Michel Husson)…

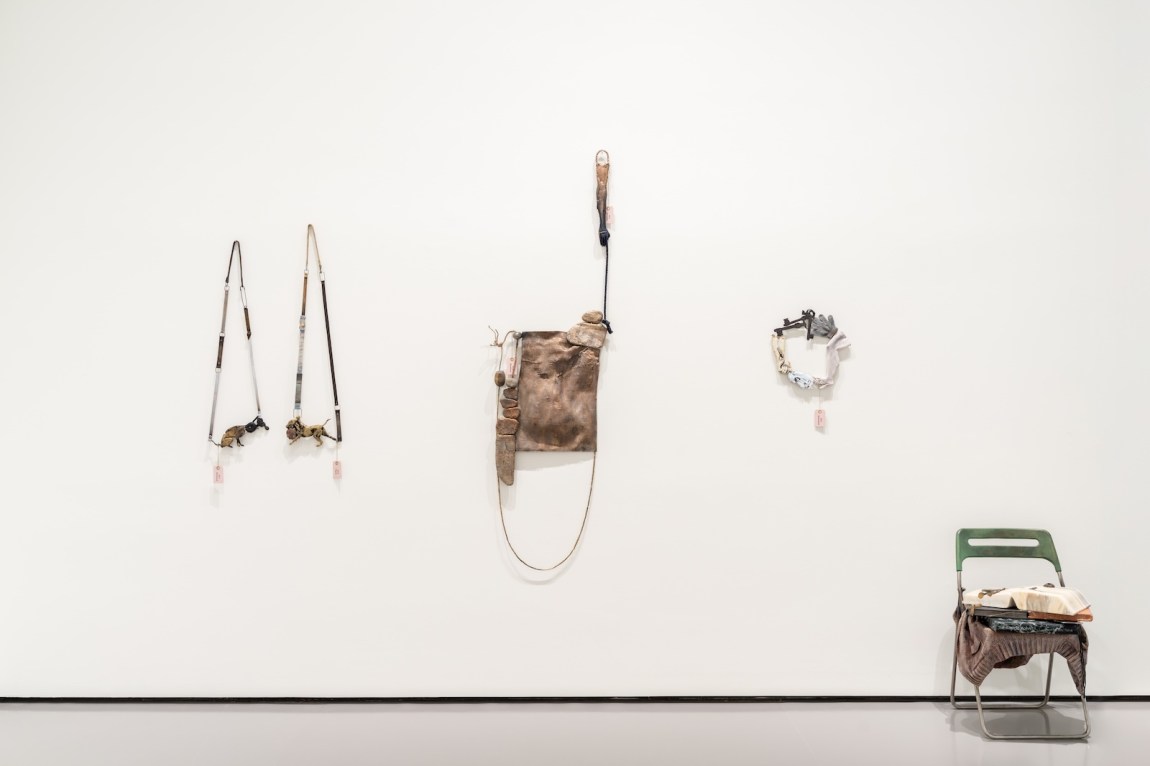

When assembled just right, her brooms and trusses and vacated seats have a bizarre compositional unity, almost a consciousness or animism. This quality is most accessible in her small wall-hung sculptures, like little Rauschenbergs without his mischief, named for the cities where she found the ingredients: a question-mark-shaped run of painted bronze cigarette butts from Graz, Austria, or a sideways “P” of beach metal from Orford Ness, on the coast of England, patinated to a tetanus-inducing shade of rust.

Art-history-wise, you want to place this obsessive mind, but it’s tough. Despite her name and her apparent fondness for Duchamp, Trouvé isn’t really a “found object” artist. Her assemblages are too mannered, baroque. (Some are painted with esoteric diagrams.) Neither is “assemblage” really true, because she makes everything. (Or nearly. The occasional real-life object, usually twine, sort of disappoints you in a show so rooted in an assumption of credibility, though you feel no right to complain.) Her devotion to illusion—braided bronze shoestrings and lanyards, cracked pleather seats—seems to place her with the recent wave of photorealists who want to shock us with the unlikely materials they choose for their replicas: Kathleen Ryan’s huge glass-bead sculptures of moldy food, Zhanna Kadyrova’s sliced rock loaves of bread evoking wartime austerity in her native Ukraine, Lucy Sparrow’s cutesy felt bodegas, Brandon Ndife’s politically ambitious cast resin junk, Kiyan Williams’s White House cast in dirt.

But no fit there, either. For one thing, Trouvé’s copies are pretty much resistant to any angle of contemporary society or politics. They are unfashionably, hermetically psychological. Because of all the accidents of circumstance they seem to allude to, these monuments commemorate all the unconscious ways that the physical world impresses itself upon us, much like the stick charts of ocean swells made by Marshall Islanders, the opinionated atlases of Saul Steinberg, or the “brainscapes”—cerebral maps of locations and objects—that neurologists have discovered we unknowingly form in our cortexes and access every day.1 The many marble books in the show, aside from proving that Trouvé is multilingual and world-curious, have mainly been chosen, as far as I can tell, less to identify her work with any particular literary or historical tradition than to allude to the liberating powers of premodern modes of thought: How Forests Think, The Dawn of Everything. In Venice she mocks the hubris of the naming project with a suitcase in bronze, labelled with a hundred possible titles, mediums, and dates for the work shut within.

Setting her most apart is medium. No sculptor alive, at least no sculptor I’ve seen, remains so true to modernity in what is basically a language of antiquity. Charles Ray is edgier, Martin Puryear and Andy Goldsworthy more sage. Trouvé makes dispassionate, ironic, effervescent anti-monuments using profoundly inconvenient methods of a distant past. She selects her hunks of marble, onyx, granite, and sodalite from a wholesale yard in Naples where stones from demolished buildings are brought for purchase, she told me by phone. Her foundry of choice there, Nolana, cuts the pieces to size. At that point she uses a chisel for shape, then grades of sandpaper for texture, until the puffer jacket or purse emerges.

For the metal, also with Nolana, she mainly uses the lost-wax method, in which bronze is poured into the empty shell between the cast of an object and an internal support, then cooled, then smoothed. It is the method of Benin and ancient Greece. With soft items, like the string bags that cradle her stone books, she must cut the bag flat, cast it in ten pieces, then solder the sides back into a three-dimensional whole. Then patinas: blacks, browns, yellows, Statue-of-Liberty greens that draw attention to the metallic nature of the illusion, as do the flopped, alloy-colored firehose forms of her claustrophobic installation The Residents (2021–2025). When she casts a thistle, such as the one that dangles upside-down from the rusty plaque of Orford Ness, she can only take a mold of such a fragile item in a way that incinerates the original. The bronze becomes the only record. Or a partial record: bronze cools at a reduction of about three percent.

Stone is tricky, too. It likes to crack. These problems make planning tough for any sculptor, let alone a joiner. When Trouvé wants the two materials to meet flush—as in the case of a 2019 Guardian in which a pillow spills from an armchair and puckers to cradle a portable radio, as if the sitter has just dropped the device to go check her laundry—she must file down the bronze radio by degrees, then check its fit in the marble cushion, then repeat, many times, till the two are snug enough to uphold the illusion.

At this scale, material polychromy has been basically extinct since Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier in the nineteenth century. You couldn’t help but place Trouvé in the Renaissance and Baroque lineage as you passed the churches of Venice—all that book-matched marble, inlaid flooring, and ironwork—on your way back from her exhibition. With the drawings, the show was probably too big, and it gave no sense either of her thirty-year development or of her prospects for future success in more modest venues. But the mere acreage of the palazzo, a four-story eighteenth-century building that has been exhibiting art since the 1950s, allowed Trouvé to pull off some extravagant reveals. False museum “benches” that are in fact sloppily heaped casts of the very silicon molds that Trouvé has used to cast her sculptures. Rooms partitioned by enormous gates of bronze tree branches. Increasingly involved sheets of “cardboard,” padding glass room dividers or painted with fictional atlases from Italo Calvino. False galleries visible only through glass but full of further, semi-familiar sculptures that seem to hold the key to all the abandoned scenery you’ve just walked through. Tall and texturally beautiful fences of dried bronze—the result of an exploded cast, formed like a skin by the foundry floor it hugged when wet. A ground floor paved with asphalt and inlaid with casts from Trouvé’s collection of manhole covers. Walk across it, and it feels like a real street, or maybe several streets overlaid. Climb to the upper stories, look back down, and the floor is a night sky: dots shining on black.

All of this puts you, physically, between Trouvé’s surrogates for real-life things and the impressions, or negatives, that those things leave behind. These are sculptures about everything but sculpture. They remind you that objects as you know them—the madeleine when you were seven, the hair clip you left on the seat-back this morning—are in fact collections of unreliable and unverifiable mental associations that can only be made truly public through extravagant reenactments, like a seven-volume novel or a palazzo full of bizarro copies. Trouvé plays with this cognition on the grand scale. She understands how memory works and isn’t afraid of the mind-numbing effort required to teach us.

Source link