Dreaming of writing a book? This is the masterclass of how to do it

A friend of mine is opening a bookshop on a high street in Thomas Hardy’s Wessex, not far from Stonehenge. I confess that this sentence sponsors peculiar joy. To envisage this imminent and noble communitarian enterprise is to feel better about virtually everything: world politics, our economy, the intolerable cool of haute couture, the climate crisis, and the state of the nation, perhaps even my summer holiday.

It’s as if, with the prospect of Chloe’s bookshop, a new planet has swum into view. Tables stacked with bright new fiction; shiny rows of tempting paperbacks; local classics such as Jane Austen; racks of audio cassettes; the new boom market. Words, words, words. Books will furnish a room, but they also supply pocket-sized and portable classics. The free range of our imagination is the only departure lounge for the flight of the mind.

A bookshop is more than just a get-out-of-jail card. In summertime, when the living is easy, with cross-channel sailings on the horizon, it can conspire with that old dream of leaving, the escape into a redemptive idyll. Almost all bestsellers, including the now-notorious book, The Salt Path, contain some trace element of truancy, real or imagined.

This may be why so many readers believe they have a book in them, and why they nurture the fantasy of 15 minutes’ fame. Another reason for the grisly fascination with The Salt Path scandal? Publisher’s greed and self-delusion (nothing new there).

Samuel Johnson had the best riposte to the wannabe authors who landed their manuscripts on his desk. “Sir/Madam, your book is both good and original. Unfortunately, the parts that are good are not original, and the parts that are original are not good.”

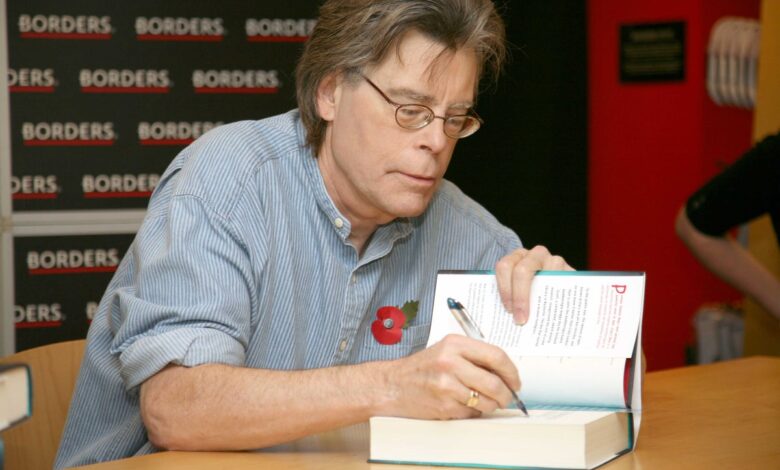

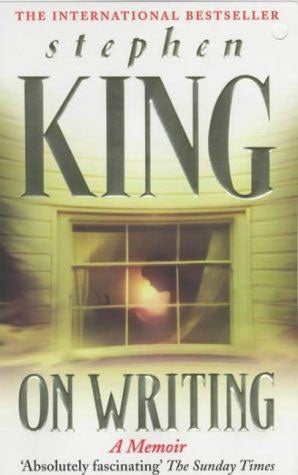

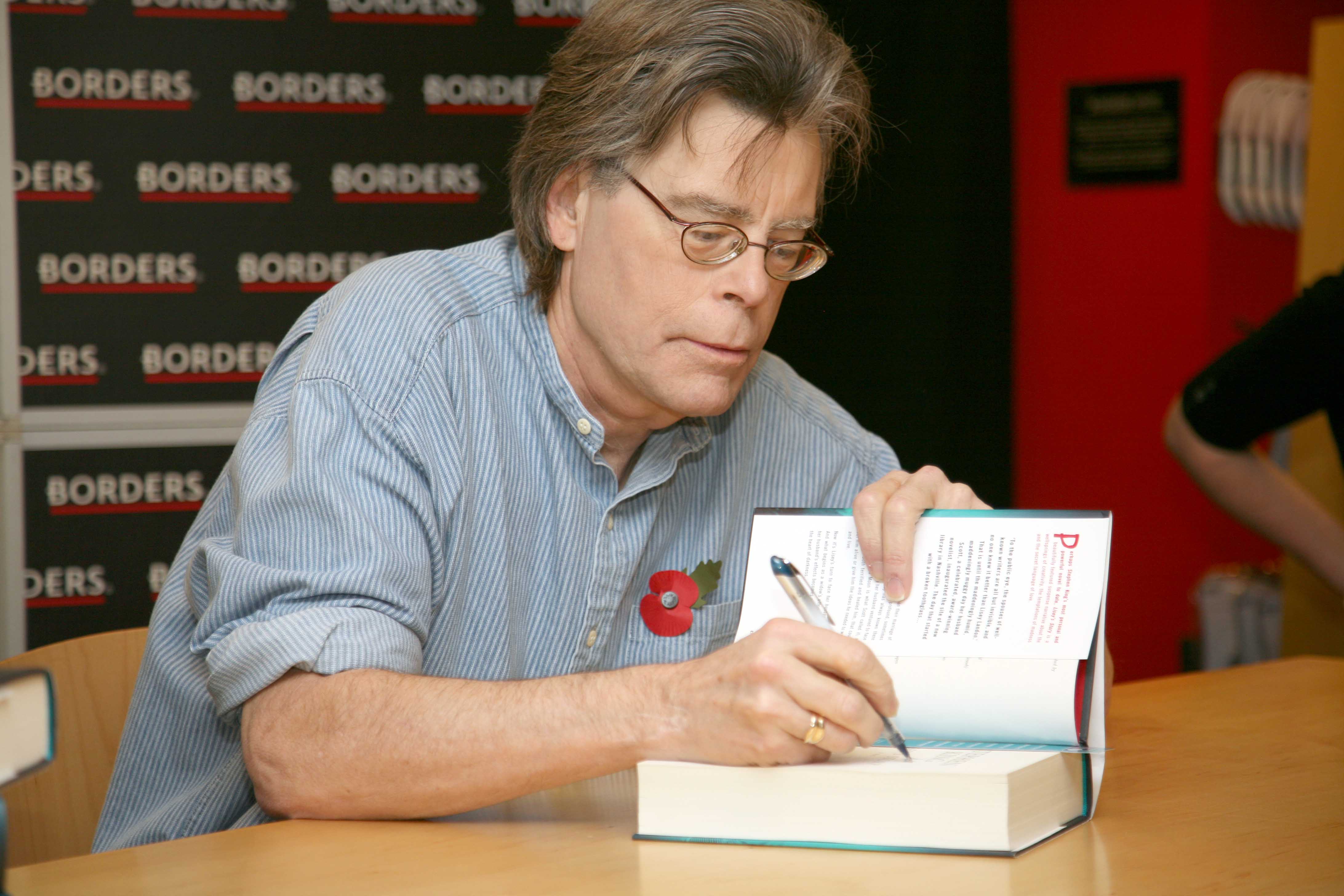

But what constitutes good or bad writing? One man who, like Hamlet, knows a hawk from a handsaw is that perennial bestseller, Stephen King. Twenty-five years ago, the author of Carrie, Misery, and The Shining published a memoir of his craft with an unassuming title, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft.

In the years between the millennium bug and the rise of the orange clown, On Writing has become indispensable. Don’t take my word for it. The names who now marshal their words to salute a masterclass in contemporary letters include Donna Tartt, Margaret Atwood, and Val McDermid. Perhaps John Grisham has it best: “If you dream of writing novels, start with this timeless book.”

King himself is never less than quotable. His opening salvo has the whiff of grapeshot that comes with all his writing: “This is a short book because most books about writing are filled with bullsh**.” He was ornery at the end of the 20th century, but for reasons we’ll come to shortly, King now sounds almost dithyrambic. This “hardback classic” arrives tricked out with sky blue end-papers, a bookmark, and a foreword “On Joy.”

Joy is the vibe, King says, he habitually gets from his “delight in the story”. And it’s this variety of joy – shivers of dread and wonder – that he wants to pass on to his audience. Like every successful writer of fiction, in any genre, I’ve ever encountered, in person, or on the page, King is all about story, story, story. He shares this preference with his polar opposite, EM Forster, who declares, in Aspects of the Novel, “Yes – oh dear, yes – the novel tells a story.”

King, who, in blurb-speak, is “one of the great storytellers of our time”, knows more than most about the DNA at work here: a narrative gene in our Stone Age brains that will always insist on an answer to the question: “What happened next?”

King may not be intimidated by the mysteries of the novel, but he’s under no illusions. Writing fiction is “a difficult, lonely job”. Writing a long book, for him, is “like crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a bathtub. There’s plenty of opportunity for self-doubt.” Like Hamlet, the novelist can find themselves, in the middle of a first draft, exclaiming “O what a noble mind is here o’erthrown.”

To meet this challenge, King’s magic formula is plain and simple: you just have to do two things “above all others” – read a lot and write a lot. Such advice, of course, is never plain, and rarely simple, and it disguises the raw, uninflected drive that King, as our guide, brings to every line he writes. The more you read, he writes, “the less apt you are to make a fool of yourself with your pen”.

At the same time, he accompanies the example of his craft and ambition with the practical wisdom of basic common sense. He advocates writing at least 1,000 words a day (he habitually cranks out an awesome 2,000). First and last, King, the writing mentor, is hands-on and down-to-earth. He seasons these instructions with many asides drawn from shared experience, buttonholing the rookie novelist with his own f***-ups and vicissitudes.

His method? To put one word in front of the next. His ambition? To entertain and hold his readers’ attention. He’ll do this come hell or high water. Even when events conspire to stop him from writing, he’ll keep on keeping on… writing.

On 17 June 1999, King was taking his daily walk down an obscure stretch of blacktop highway in western Maine when a blue Dodge van swerved onto the hard shoulder (King’s hard shoulder). The driver, one Bryan Smith, claimed he’d been distracted by the antics of his rottweiler Bullet snaffling fresh meat from the back seat. Actually, Smith had a terrible record as a rotten driver and an ocean-going weirdo. His first thought, having pranged King, was that he’d just “hit a small deer”.

Mercifully, King was not going to die, but his impact injuries had reduced him to a bag of bones, in the words of his surgeon, like “so many marbles in a sock”. Just five weeks after his shattered frame was helicoptered off Route 5 in the aftermath of his contretemps with the Dodge van, he says, “I began to write again.”

In the face of such dedication, I agree with Atwood, Tartt, McDermid – and yes, King’s devoted publishers, who have splashed out on this souvenir volume – On Writing is indeed a classic.

There are many definitions of what a classic text is, of course. Inevitably, the issue is intensely subjective. Classics, for some, are books we know we should have read, but haven’t got around to. For others, classics are the books we’ve read obsessively, many times over, and can quote from. For some an addiction; for the rest, quite scary.

One necessary, but not sufficient, characteristic of a classic is that it should be available. As Chloe, the bookseller, likes to say, “Dead, but in print.”

In an era when the literary tradition we inherited from the late-20th century is being redefined, it’s become a list that still includes Charles Dickens, Austen, Charlotte and Emily Bronte, George Eliot, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Taylor and Penelope Fitzgerald, but few other certainties.

The so-called common reader instinctively knows what they believe to be a book for the ages. One thing’s certain: come the autumn of 2025, there’s a high street in Hardy’s Wessex where you’ll be able to indulge your curiosity about the works of at least one classic American writer who – praise the lord – is happily not dead yet.

Stephen King’s ‘On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft’ (Hodder, £22) can be bought here

Source link