Indies Introduce Q&A with Julian Brave NoiseCat

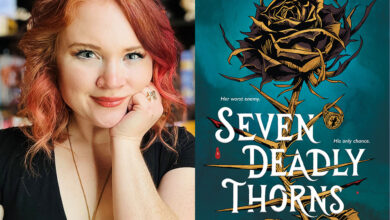

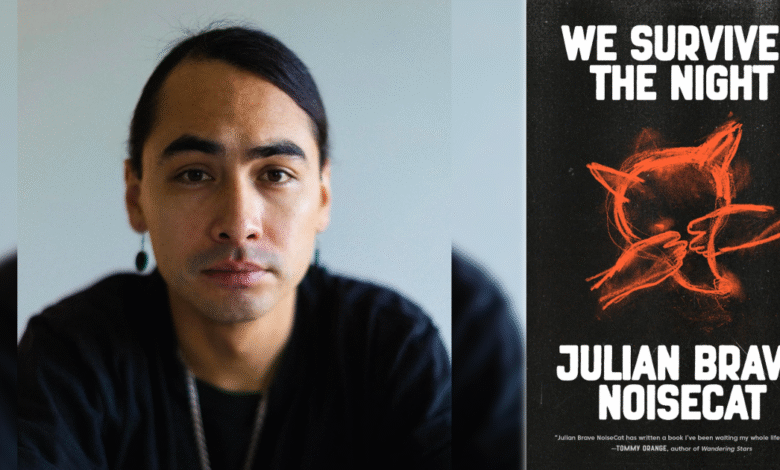

Julian Brave NoiseCat is the author of We Survived the Night, a Summer/Fall 2025 Indies Introduce selection.

Marisa Spence of Ballast Book Company in Bremerton, Washington, served on the panel that selected NoiseCat’s book for Indies Introduce. She called it “a unique and necessary Native American tale, woven with history, stitched with memoir, and embroidered by myth.”

NoiseCat sat down with Spence to discuss his debut title. This is a transcript of their discussion. You can listen to the interview on the ABA podcast, BookED.

Marisa Spence: Hi, I’m Marisa Spence. I’m a Marketing and Social Media Manager and bookseller at Ballast Book Company in Bremerton, Washington. I was on the Indies Introduce panel for the Summer/Fall 2025 titles, and I’m excited to talk about one of our selections, We Survived the Night.

Julian Brave NoiseCat is a writer, Oscar-nominated filmmaker, champion powwow dancer, and student of Salish art and history. His writing has appeared in dozens of publications, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The New Yorker. NoiseCat has been recognized with numerous awards including the 2022 American Mosaic Journalism Prize and many National Native Media Awards. He was a finalist for the Livingston Award and multiple Canadian National Magazine Awards, and was named to the TIME100 Next list in 2021. His first documentary, Sugarcane, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary. Directed alongside Emily Kassie, Sugarcane premiered at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival, where NoiseCat and Kassie won the Directing Award in US Documentary. NoiseCat is a proud member of the Canim Lake Band Tsq̓éscen̓ and descendant of the Líl̓wat Nation of Mount Currie. We Survived the Night is his first book.

Hi, Julian!

Julian Brave NoiseCat: Hey Marisa, good to be in conversation with someone from Bremerton! Ballast Books!

MS: Yes! That’s your hometown, right?

JBN: Yeah — though I’m not there that much these days — that’s where I live.

MS: Yeah, that’s fair. It’s a beautiful part of the world, for sure.

JBN: It is! Also the quality of life is good, it’s a beautiful part of the world, very down-to-earth place. I really love Bremerton.

MS: I love the artistic community there as well. Thank you for joining me on the podcast today! We Survived the Night was a book that I read earlier on in the Indies Introduce selection process, and I had a hunch from the get go that it would make the final list.

It’s so full of heart and the depth of research hooked me from the start. It was really layered, and there was such a uniqueness to its form. It has a perfect balance of history, myth, memoir, and folk tales. Did you know going into the project that that was how you wanted to tell the story, or did the pieces fall into place as you worked?

JBN: Thank you so much. That’s such a kind thing of you to say about the book. That is what I worked really hard to try to achieve, and it was definitely not something I achieved on the first draft. I’d say that the book really transformed when I made the decision to move in with my dad, who I lived with in Bremerton, for two years while I wrote We Survived the Night. This is a man who left my family when I was six or seven, and I saw him less than two dozen times between the ages of six or seven to adulthood. I even had to lend him money to come to my own high school graduation.

We definitely had some history and some distance, and suddenly we were living across the hallway from each other. I was working on my book, as well as a documentary called Sugarcane that came out in 2024. He was an artist, so he’d be out in the studio during the day, making his art, and then at night, we’d hang out, smoke a little something, and play games. He’d tell me stories about his life and I’d tell him stories about mine.

As that was going on, I was thinking very purposefully about what traditions I felt I had a responsibility to carry forward as an Indigenous storyteller working in the wake of what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has described as a cultural genocide that nearly wiped out our language, our way of life, and our way of looking at the world and telling stories.

I was reading our old oral histories in century-old ethnographies, and I felt myself really drawn to these ones that are probably the most popular in our oral histories called the Coyote stories. These are stories about my people’s trickster ancestor, this guy called Coyote, who was sent to the earth by the Creator to set things in order.

While he did a lot of good, he was also up to no good a lot of the time; he was a great creator and destroyer. He was always out trying to trick people and then himself getting tricked. He filled the rivers with salmon and populated the lands with descendants and then he abandoned us. He used the salmon to his own advantage to try to marry into every single village along the rivers that he could. He was a bit of a scoundrel, and yet he also achieved incredibly important and great things.

Most importantly about Coyote is that he died and resurrected many times; he was a great survivor. In fact, he died and resurrected so many times that our people didn’t even bother to count. Not that it’s a competition with Jesus or anything, but in our stories, Coyote definitely died and resurrected a lot more times than Jesus died and resurrected.

In this story about this survivor, this great creator and destroyer who made the world through complicated actions, I saw so much reflection of the man who I had moved in with, my own father, and his father, and also the Indigenous world more broadly, wherein I think that there are many Coyote-like figures. If we look at the world right now, I think it’s hard not to say that this is a world that’s being made by tricksters in their tricks.

I felt that this tradition that I came from, this storytelling tradition that has basically died out — I’ve only ever heard a Coyote story told out loud by a member of my own family one time in my entire life — I believed that this tradition had something to say to literature, to the humanities, to nonfiction, because we’ve always considered the Coyote stories nonfiction.

I really wanted to try to do something that I’d never seen, which is to write a narrative nonfiction text in the form of a Coyote story that would bring this dead tradition of my people back to life on the page, because I saw that it had so much truth in my own life and in the world as I saw it.

MS: That’s really interesting that you see your people in the story of the Coyote, and find that sense of relatability between them. Earlier you spoke about this evisceration of storytelling, mythology, the language, and I’m wondering if the title We Survived the Night actually has anything to do with that, with this death and resurrection, or surviving the violence and atrocities that people have faced.

JBN: It absolutely does, but it also is another thing that I derived from my own people’s culture. In this case, it’s our language. The very first thing I knew about the first book I wanted to write was that it would be called We Survived the Night. That was because, in Secwépemc, my people’s language, a language that I’ve spent time learning with my grandmother — a language that now only has two remaining fluent speakers on the Canim Lake Indian Reserve, and has nearly almost died out — the way that you give the morning greeting is you say “Tsecwíncuw-k,” which literally means “you survived the night.”

I thought a lot about what it must have meant for my ancestors to greet one another in the day by saying something as profound as “you survived the night.” What did that mean in the winter of 1862 to 1863 when two-thirds of our nation died of smallpox? What did it mean to say that to one another in the days after they took the children away to the Indian residential schools?

I also think about the almost dark comedic sensibility in the word, and the way that my own grandmother, who taught me the language, sometimes uses it. When she would teach me language, she would have a coffee mug that had “Tsecwíncuw-k” written across it, which I thought was so ironic. It was “you survived the night” in a language that is barely surviving the night, to a woman who herself is also a survivor.

Sometimes when I say “Tsecwíncuw-k” to my grandmother, she’ll say something like wry and witty, like, “Oh, don’t remind me.” That gets at so much of what it is to be Indigenous, what it is to have lived in the wake of the near entire death of your people and your way of life. But it also captures our sensibility and our relationship to that story. I’ve always felt that the book would follow in the structures and ideas that are indigenous to my own people and our own experience. That began with the title and the word that it’s referencing in our language.

MS: It’s interesting that it has so much related relatability to the history and past violences that were committed as well. Do you think it has any relatability to present-day — because the book We Survived the Night has a lot to do with modern day Indigenous people and their cultures and how they live?

JBN: I think it’s relevant to contemporary Indigenous life. If you look at the statistics of misery, including our expectation of death age, especially for Native men, we fall at the bottom of all of these categories statistically. My dad likes to joke sometimes that he’s 66 but he’s 95 in Indian years. I think he’s now past the expected age of death for a Native man in this country and in Canada.

It’s a real thing. During the writing of the book, I attended ten funerals for members of my nation, over half of whom I was related to and the majority of them were people who are under 45. The existential reality of being a Native person is still a very real one.

In this current moment, where we have questions about the death of our way of life in America, questions about the death of democracy, about the rise of authoritarianism, I also think that the story of Indigenous survival has something to lend to a much broader audience than just Indigenous peoples. The story of how people survived what was an arguably theocratic and authoritarian system that deprived us of the basic right to parent our own children, might give some understanding of the roots of authoritarianism that are homegrown right here in North America, but also tell a story of resilience and hope and resurgence in the wake of that kind of reality, because at the same time as Native people are still succumbing to the legacy of colonialism and cultural genocide, we are also coming back. The book is full of stories of political leaders, of activists, of artists, of nations, of grassroots community organizers who are helping bring back our people on our way of life and our culture, and actually having some significant success in doing that.

MS: Yeah, there are so many important stories to be told, and in a way, telling the story helps keep everyone alive. I really like that you’re doing the book, but you also are telling stories within other media, such as your film Sugarcane, which was nominated for an Oscar. Congratulations to that again!

How are the movie and the book connected to one another, and how do they tie into each other and tell these different stories?

JBN: I wrote and directed Sugarcane at the same time as I wrote We Survived the Night, so they inevitably influenced each other. While that’s true, you don’t have to watch Sugarcane to read We Survived the Night, and you don’t have to read We Survived the Night to watch Sugarcane, they are distinct projects. We Survived the Night has a much broader scope of story that it’s telling. We Survived the Night is more broadly about what it is to be Indigenous to the United States and Canada today whereas Sugarcane was more specifically about the system that nearly wiped out our people and our way of life. The way that that really shaped the writing of We Survived the Night is that I spent all this time thinking about this system that had made it so that I had to relearn my people’s language. So much of our culture has been lost; it created a situation wherein the way that I learned the Coyote stories, for example, was by reading old ethnographies rather than learning them from my own family members.

That made me approach the act of writing a book and telling stories in a very purposeful way, and that was to ask myself what my responsibility was as an Indigenous writer, as an Indigenous storyteller who works across multiple mediums. What do I have to help bring back? What are the pieces of my people that were taken away and nearly cast into the wastebasket of history, that have been positioned as though they have nothing to add to storytelling, to the humanities, to our understanding of the world, that actually, on the contrary, really do.

On its face, it’s ridiculous that we don’t look to the traditions of First Peoples to understand this continent. We’ve been here for thousands and thousands of years; we were here when the coastline looked different, we were here longer than many of the forests that now cover the continent, we were here before the waterways took their present shapes. The stories that we tell in one of the Coyote stories that I write about in the book talks about when the salmon first went up the Fraser River. Interestingly, the place where we place the dam that prevented the salmon from going up the river is the same place where archeologists and experts who study this thing say there was an ice dam at the end of the last Ice Age that also prevented the river from taking its present course.

My point here is that these are stories that have elements that are thousands of years older than the Bible, and that get at how an entire group of people understood the world and how it transformed themselves and our role in it in a way that was actually quite capacious, that has room for both wonderful acts and complicated self-serving acts, and that also still rings quite true today. Again, I would return to the current events, like you can’t tell me that the current president, who you know is the most powerful person in the world, is not, in his own way, a trickster, and that this world is not made by tricks. The entire continent of North America was stolen from its First Peoples — that’s as great a trick as I could ever imagine.

I feel like I have to insist over and over again that we need to take these stories and these traditions seriously, because, of course, they get at so much of the truth of this land in this world.

MS: These stories are still so important. We Survived the Night still lives in my own heart, and I read it six, seven, eight months ago, and there are so many themes within it that resonate today and will continue to resonate and that are so important for people to dig into.

A lot of these themes were so dichotomous with each other, but they ring true and they hold weight and they hold depth there, they are relatable for everybody and they are themes that need to be told in stories today; love and hate, pain and peace, life and death, and those are themes that are true basically in every story, but are just so particularly important in We Survived the Night. How did it feel to explore these themes in the current climate, but also with a book that is so close to your own personal self?

JBN: I think that part of what is so special about nonfiction is that nonfiction is about how we choose to live our life and to observe the world and the stories we see around us. In fiction, you get to write the scene in whatever way is the most creative and powerful and all that sort of stuff. In certain ways, that has a leg up on nonfiction, except that in nonfiction, we actually get to be there for the story. It’s a real story.

In many instances, it’s a story that you were present for, that you chose to live in that way.

If you think that through to what that means for people whose way of life, whose way of seeing the world, of telling stories and of being, was nearly wiped out, what is really profound about approaching this book, making the decision to move in with my dad, and spending so much time traveling to my own Indigenous community and many others across North America, was that it called me to live in a very Indian way, a way that felt much more purposefully true to my people and my ancestors after making a career on the East Coast, thousands of miles away from where my people come from.

What I have come to understand about the way that we tell stories is that to tell a story about someone is to say that you know them. It’s to say that you have spent enough time with them that you were with them when this happened, or you know this story about them or their ancestor, or about who they are, something funny, something really insightful, something sad, something that combines those things.

In that way, telling complicated stories about complicated people acknowledges the fact that we are all complicated human beings. That we all have things about ourselves that are wonderful and deserve to be embraced, there are things that maybe make difficulty and pain for others around us, including the ones we love. At the end of the day, telling a story about someone that sees them fully is to say that I know this person so well that here’s a story that I, and I alone, can tell about them, and that is evidence of my love for them.

That’s what I see my own people do very often when we tell stories about one another. I really wanted the book to be part of that act of getting at some hard truths that have hurt me and other people, but doing it in a way that still had love for the people who I was telling a story about.

MS: Yeah, I definitely agree with how vital it is to keep telling these stories and to keep creating art, especially as you mentioned earlier, in the current political climate. Some people say that storytelling and art shouldn’t be political, but I’ve always said the art is war, and it’s so important to be making these statements and to be telling these stories and to continue loving one another through the stories.

JBN: I think that it’s possible for us to tell stories about difficult histories, even ones that include members of our own family. There are lots of forces in the world that would like us to shy away from telling hard stories about one another and our nation. I just think that it is very possible to tell hard stories in a critical yet loving way, and I really hope that that tradition does not die out.

MS: We Survived the Night has a lot of different themes; it ties in the history, mythology, your own personal life, it contains multitudes. But if you could describe it in one word, what word would that be?

JBN: I’ve used a lot of words from my own language, from Secwepemctsín, so I will spare the listeners yet another. There’s a thing about German words, for whatever reason, in literary and academic circles, and I picked up a new German word while I was writing and researching We Survived the Night, and it is “weltanschauung,” which means a particular philosophy or view of life, or the world view of a group of people.

One of the things that I’m really interested in conveying in this book — like the Coyote stories for example — is the weltanschauung of my people. It’s my hope that doing nonfiction in this unconventional Indigenous way, bringing our nonfiction traditions in conversation with more conventional traditions of memoir and journalism and criticism, helps continue the renaissance and resurgence of Indigenous art and storytelling that I’m seeing all across North America. It’s a really beautiful thing that I hope continues.

MS: I think it will, especially with the publication of We Survived the Night. It’s out very soon, and I know a lot of booksellers are already so excited for it, and especially after listening to this interview, they’re gonna have even more to talk about and even more excitement for it. I hope you’re excited that it’s publishing soon as well!

JBN: I’m super stoked. We love the indies, and I’m really grateful to all the mom-and-pop shops out there that are keeping our artform alive and getting books into readers’ hands. It means the world.

MS: I appreciate that so much, and I know everybody who has ever worked and will work in an indie bookstore would appreciate that too.

Thank you for joining us on our podcast, congratulations again to We Survived the Night on the Indies introduce selection, and I can’t wait to see what else you bring us.

JBN: Thanks, really appreciate it.

MS: Thank you!

We Survived the Night by Julian Brave NoiseCat (Knopf, 9780593320785, Hardcover, History, $29, On Sale: 10/14/2025)

You can learn more about this author at julianbravenoisecat.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.

Source link