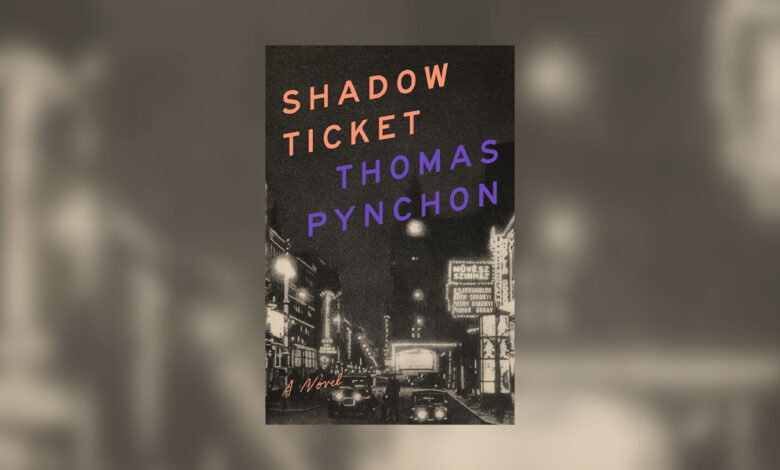

Thomas Pynchon’s New Novel Is a Feast of Milwaukee Oddity

If you have ever read a paragraph of a Thomas Pynchon novel – the proto-hippie California double-speak, the switchback internal monologue, the future flashback, the West Coast geographic specificity, the every-which-way plot plus the possibility that every word is the shaggiest dog story you’ve ever read (until the next page) – then you might be as surprised as me to discover that Pynchon’s new novel, Shadow Ticket, is set in Depression-era Milwaukee.

I purport not to “get” Pynchon’s novels insomuch as they can be “got,” but I dig them quite deeply for their periscopic polyrhythmics, their inevitable underbelly, the psychedelic noir, the pragmatic paranoia, their belligerent honesty and ultimately, their heart. The famously reclusive writer’s books are rich with characters unglued by the 20th Century and all its unfulfilled promise: for my money, no author better dismantles and repositions the American dream. Like the soldiers force-fed LSD by the US Army at Edgewood Arsenal, Pynchon’s people struggle unwittingly versus unnamed, unknown sources of influence, guided by love, by lust, by the green-glow of Gatsby’s psychosis at the always blooming American horizon, unsure if the growing light in the sky is the sun, nuclear fallout, a happy ending or the end of the line.

Pynchon worked at Boeing in the early 1960s, witness to the Cold War projectile hysteria, shaking hands with the engineering madhatters whose very fingers twitched above the doomsday switch. In other words, if you’ve yet to read him, it’s important to know that Pynchon frequently writes about what went wrong in the American 20th Century, often from the perspective of complex, confused, horny, hungry, unforgettable and slyly sympathetic humans, all trying to piece together the confetti of jigsaw they’ve become. Pynchon’s tales of counter-counterculture California in The Crying of Lot 49, Vineland and Inherent Vice, as well as the belligerent erection of American missiles in the 1974 National Book Award-winning Gravity’s Rainbow (yes, I’ve read it and no, I don’t understand it) made coastal sense, relative to his obsession with America’s violent frontier, but suddenly, at age 88, Pynchon has poured an historical fiction mickey into Milwaukee’s very own Brandy Old Fashioned.

How does Pynchon place his periscopic stamp on Cream City in his Milwaukee-centric Shadow Ticket?

For starters, it’s Prohibition in our fair city – you can imagine how well that went down – and the cops are busy, but so are the bootleggers, the pinsetters, a “one time male flapper,” a lost Hungarian submarine and some little German guy with Chaplin’s mustache. There’s Brady Street Italians getting fingered for every violent crime, ham radio enthusiasts catching signals under the Holton bridge. Pynchon sprinkles “Milwaukee bildungsroman” (I had to look that up), Bowling Ball Hospitals, Korbel Brandy (of course), sheepshead, radioactive cheese and so much more Milwaukee-specific sauerkraut into the story. And he nails the nomenclature: at the Milwaukee Courthouse, steno girls are “gossipping around the bubbler.”

Another prime example of Shadow Ticket‘s local specificity: “Uncle Lefty has tactfully avoided mentioning that the streetcar route takes them across the Menominee Valley via the Wells Street Viaduct, 90 feet up, iron, black, rickety in the wind, not for nervous passengers or even those with their wits about them who’d prefer to get across in one piece.”

So what’s the story about? It’s 1932 Milwaukee and Prohibition is nearing its end, but the speakeasies and all the accompanying crime, repression and chaos of the blossoming Depression are in full implosion. Pynchon’s main man is Hicks McTaggart, a self-described “gumshoe” who packs heat and finds scraps aplenty with crooked cops, cocky mobsters and the occasional “truculent little Bolshevik.” Hicks, as he’s referred to throughout the novel, was one of Milwaukee’s finest and a former skull-busting strike-breaker, but he’s recently turned Private Investigator after he began to “feel a spiritual heavysetness sneaking up on him.” Like turning a Julie Andrews ditty into a Coltrane masterpiece, the weight of consciousness twisting his characters toward a desperate reach for redemption is one of Pynchon’s favorite things. Hick’s main squeeze, a singer named April, might also be the main squeeze of an organized crime boss, and between their nights dancing in Bronzeville and a meeting via “Paramount platters, straight out of Grafton,” they must part because Hicks has some debts to pay.

Hick’s debts mean he’s on the job, like it or not, to track down Milwaukee cheese heiress Daphne Airmont, who, against the wishes of her wealthy family, has “gone hepcat.” Daphne split town southbound to the Windy City (or parts unknown) with a clarinet player of the dreaded Jazz persuasion and the Airmont family is aghast. Daphne’s departure makes headlines throughout the Midwest, headlining papers like Lowlife Gazette as being on a “DAIRY DEB SIN SPREE.” This is more than her cheese-baroness mother can digest. Against his will, Hicks is hired, coerced, forced by…who? The Arimonts? The newly minted Milwaukee branch of the FBI? MPD? All of the above?

Hard to say, but he’s off and running to parts within and beyond Milwaukee but not before we consider how high the Menomonee street cars once ran, Original Sin on the Southside, Wisconsin Lasagna (raccoon, anybody?) and the most Pynchonian question of all, asked by The Department of Cheese Studies at the UW branch in Sheboygan, best left unanswered so that you read Shadow Ticket immediately: “Does cheese, considered as a living entity, also possess consciousness?”

If questions like this intrigue you, my fellow Milwaukeean, and you are a fan of all the oddity and glory to be found among the Streets of Old Milwaukee, Pynchon’s new novel is most certainly your Ticket to ride.