Graphic storytelling evolves in Longform’s third anthology

This is the third volume of the Longform anthology of graphic narratives, the first having been published in 2018. The title refers to the group of comics artists and self-confessed fans who are its editors. The original group consisted of Pinaki De, Debkumar Mitra, Sekhar Mukherjee, and Sarbajit Sen. This time, Argha Manna joins De and Mitra as an editor. The book contains 17 stories and 1 interview, with Joe Sacco, the well-known cartoonist, who was back in the limelight recently with his book War on Gaza.

Comics anthologies are one way Indian publishers have engaged with the medium. Some of them are thematic, like the First Hand volumes (edited by Vidyun Sabhaney, 2016, 2018) that focussed on non-fiction. Others, like This Side, That Side: Restorying Partition (edited by Vishwajyoti Ghosh, 2013) focussed on the historical event of the Partition, which created India and Pakistan.

In relation to anthologies like these, Longform seems to position itself as a free-flowing collection of experiments with the form of comics. The word “comics” is not used in the title. It describes itself as “An Anthology of Graphic Narratives” instead. Immediately, that allows for a certain flexibility with the medium. Many of the works, therefore, are in a space somewhere between comics and a picture story.

Also Read | Shift, control, caste

The very first work, “Text Box” (Anantha Sriya A.), is a case in point. Composed of minimalist drawings that sometimes function as illustration and sometimes as a sequential panel, the work also has free-floating text without any drawing associated with it. At one point, there is a whole page of text without paragraph breaks that bleeds into the edge of the page, with parts of words deliberately cut off. This turns the text almost into an image of its own. The text unboxed, as it were.

Longform 2025: An Anthology of Graphic Narratives

Edited by Debkumar Mitra, Pinaki De, and Argha Manna

Vintage Books

Pages: 320

Price: Rs.1,499

The story is told in the first person, by an unnamed male narrator who is almost unseen, except once from the back. A passport-size portrait drawing of the narrator’s daughter is the only other “character” that appears. The narrator ruminates about following his passion for painting. No other cultural specifics are given. Only at the end—a double page of large text in Telugu that reads: “The world speaks many tongues…”—do we get a hint of cultural background.

Moments of clarity

The editors clearly intended that as a sort of manifesto for what is to come. Diversity and plurality is the motto, while the voices tend to veer towards soliloquies and interior monologues. A moral lesson is delivered in such a soliloquy in “My Conversation with God” by Khushi Chauhan. The son of a brahmin temple priest is forced to take up his father’s job but has health issues inhaling incense. He moves cities, takes up other jobs, marries, and then loses his wife to illness.

Alone, he turns to the Gita. A shloka entreats him to look inward. He has a moment of clarity. This inward gaze is evident in many of the other stories. “Grief” (Avanti Karmarkar) literally has a person tearing her chest to reveal the darkness within. The spiral becomes a symbol of going ever inward. This subjectivity turns into memory and nostalgia in stories like “City of Missing People” (Priyankar Gupta), “An Elegy” (Santanu Debnath), and “Remembering” (Sid/Pyre).

Longform positions itself as a free-flowing collection of experiments with the form of comics.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

“City of Missing People” is a nostalgic look at the city of the author’s childhood and youth. Told in an allegorical mode that suits the comics medium, the city of Kalishahor (Kolkata) is depicted as a gloomy nightmare that has lost its people and its soul. There are only ghostly remnants of its past. In “Remembering”, painful memories are brought to the surface: a pregnant womb rips apart to turn into a huge eye. Such metaphors haunt this volume.

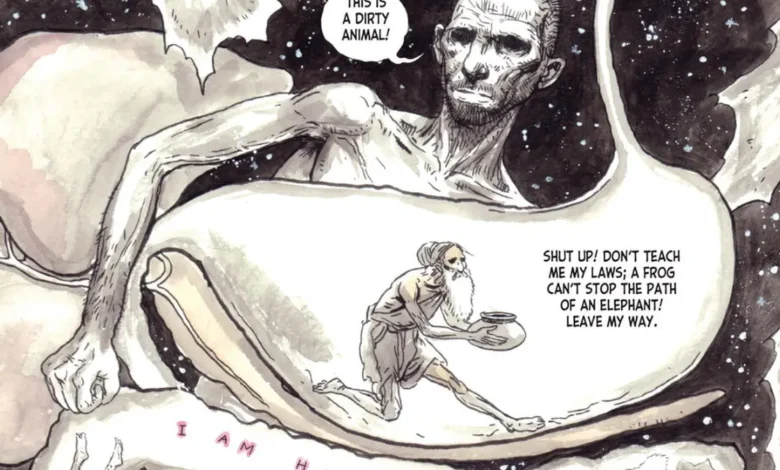

There is a persistent tone of melancholy in many of the works. It continues in another tale, this time from the Mahabharata (“The Laws of the Ancients”, Sankha Banerjee). The war is over. Bhishma lies on his bed of arrows. Yudhishtira has conversations on dharma with the dying Bhishma, who tells him a tale where in a land that is corrupted and ravaged by famine, the sage Vishwamitra, hungry for food, is forced to consume dog meat, in a breach of tradition. The moral lesson is ambiguous as the gods send rain after that act.

The mythological tale is rendered with a degree of realism that is not found in other stories that are actually set in contemporary times. Indeed, reality seems to have the appearance of dreams and nightmares. In “Genesis” (Gargi Bhattacharya, writer; Subhasis Ghosh, artist; Shan Bhattacharya, visualisation), yet another soliloquy, a young woman is pregnant, and her anxieties about whether to keep the child turn into a melancholic dream. The face of the protagonist is almost hidden, never fully revealed; a curious feature found in other stories as well.

Also Read | Bull, man, power: Vaadivaasal and the politics of pride

This sombre mood takes on another tone through works that touch on ecology and environmental issues, like “Resorts to Ruins” (David Lo, writer; Kay Sohni, art) and “Earworm: Requiem for a Species” (Pratyasha Nath). The environmental impact on the Salton Sea, California’s largest lake, is the subject of the former. A graphic narrative without any characters, it goes through depressing statistics and ends with an image of a solitary armchair on the banks of the drying lake. “Earworm” turns the focus on parasites, using a personal voice to articulate ecological concerns. Artistically, this one mixes realism and symbolic imagery in a skilful manner.

The one interview in the volume, tracing Joe Sacco’s oeuvre so far, is enlightening and stands out in contrast with the other stories. Sacco’s work is resolutely outward looking, engaging with the ugly material realities of our world, reporting what he sees, as opposed to the strong sense of inward looking found in the anthology. That said, Longform continues to showcase the form to Indian readers, and the more we have such spaces, the better for comics and graphic narratives.

Bharath Murthy is a comics author and editor-publisher of the independent comics label Comix India.

Source link